Expressing Identity through Art

Over the centuries, many artists have used art as a vehicle for exploring questions about identity. Even though our ethnic heritage or sexuality informs who we are, identity is fluid rather than fixed. Our personal experiences as well as the sociopolitical realities of our time can revise how we see ourselves or how others perceive us. As both individuals and members of communities, we keep reconsidering our place in the world, wherever we live. This is especially true for those of us who are immigrants.

Mills College Art Museum, Oakland, CA

When I was invited to a reception at Mills College for In-Between Places: Korean-American Artists in the Bay Area, I immediately knew I wanted to attend. As an immigrant to the U.S. when I was just a child, I am familiar with this search for cultural identity and trying to figure out where you belong. The eight artists who created new work for this show exist bi-culturally: their art is not considered American in their adopted country nor Korean in their home country. Using approaches to art making that are traditional and contemporary, Korean and Western, the artists express the reality and complexities of this ambiguous identity.

"Turn Right, Turn Left" (2017), four-channel video installation by Minji Sohn.

Minji Sohn's video installation in an enclosed space invites visitors to fully experience her intense performative art by stepping on the small stage and following directions. Moving back and forth amid fast flashing lights feels discomfiting and disorienting. It's what Sohn has felt all her life as she flew between continents every few months, living in between countries and cultures. Turn Right Turn Left examines categorization itself through the constant shifting between two options: move or stand still, become part of the crowd or go it alone, dress in black or white. Seeking to find her way as an artist, Sohn has realized that complying to an authoritarian voice that instructs her which way to turn leads neither to resolution nor to an ultimate destination. Instead, she has created a manifesto for herself, though she doesn't suggest that it's advice for other artists:

Let us not be bound by ideas of how we must be. Let us not be told to be or do anything that feels wrong. Let us define for ourselves what the right timing and the right places are. Let us speak the unspeakable and question the obvious. Let us not be afraid of being hated, disgusted, shamed or pointed a finger at. Let us not be limited by meaningless, quantifiable labels of age, sex and race or use them as excuses; or let us use those labels to empower and inspire us. Let us be and make only what is true to who we are. Let us just be. Let us make no compromises.

Painted canvas under plexiglass in "Chorus of Trees" (2017), by Younhee Paik.

The individual works in this exhibit are not easy to capture fully through photography because of the spaces they occupy, the different components that comprise them, and the movement inherent in some. Minji Sohn's is one example, but so is Younhee Paik's Chorus of Trees, which consists of black and white charcoal drawings on rice paper as well as an acrylic painting on canvas under plexiglass on the floor. Taking in the artwork means walking on the plexiglass to see the colors and brushstrokes as well as looking up to see the drawings, which hang like scrolls.

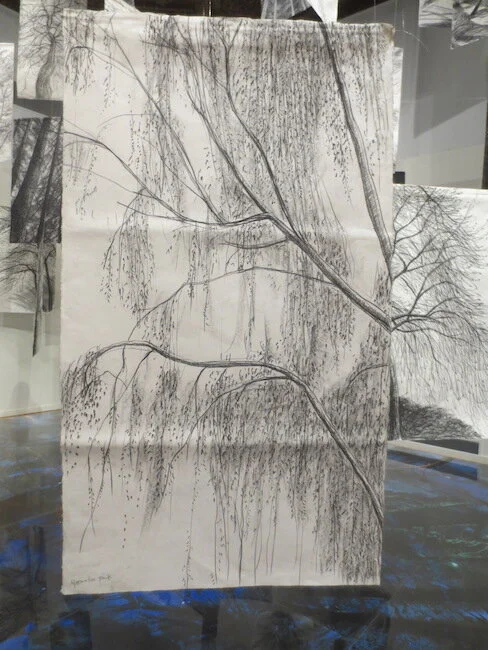

"Chorus of Trees" (2017), by Younhee Paik.

Paik offers viewers an opportunity to feel a kind of wonder, similar to when we gaze upward in an actual forest. If these monochromatic drawings were suspended outside, we might hear them rustle like real branches and leaves and hear birds flitting through them and calling out. According to Mills College Professor Mary-Ann Milford-Lutzker, one of Paik's first impressions of California was how different the light and shadows were from those in Korea. In choosing trees as her theme, she knows that our responses to Nature are universal, not specific to one culture.

Charcoal drawing in "Chorus of Trees" (1917), by Younhee Paik.

Being an immigrant often entails many sacrifices in order to establish a new life in another country. For Kay Kang, a huge part of that was missing the later years of her father's and grandmother's lives before they passed away. My Journey/Bahljhachwee and From East to West incorporates traditional socks or beosun to reflect longing for her family. To create them, she recycled Korean bed linens made of ramie (fiber derived from a flowering plant in the nettle family Urticaceae, native to eastern Asia). Her family had used the linens during the hot and humid Korean summers many decades earlier. The feet cast in plaster represent the steps she has taken during a journey of 46 years since she immigrated to the United States.

"From East to West" (2017), by Kay Kang.

Detail of "From East to West" (2017), by Kay Kang.

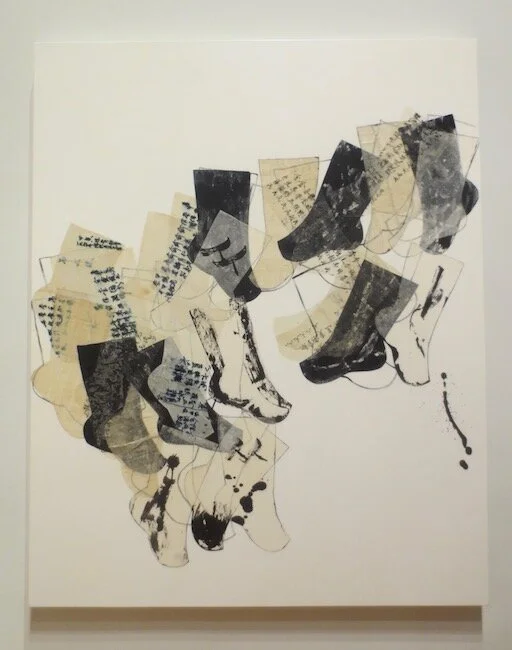

"My Journey/Bahljhachwee" (2017), by Kay Kang.

Kang also created beosun with sumi ink and acrylic on hanji (handmade Korean paper) and collaged them on canvas. She explains that these paintings describe "the life journey and evolution of women." Traditionally, Korean women wore white cotton socks not only to keep warm, but also to make their feet appear daintier. Especially in front of one's elders and men, bare feet were not considered feminine. Her beosun depict the transformation "from a protected woman to a bare-footed, independent, strong-minded woman in America." Kang admits that she might not have had the courage to express her feminist concepts in Korea, but she feels free to do so in the Bay Area.

"Guests Missed" (2017), by Kay Kang.

In Guests Missed, inspired by the guest book Kang received from her family in Korea, the beosun are inscribed with letters and records of visitors who attended her grandmother's memorial in 1974 and her father's a year later. At the time, her family decided not to upset her by informing her of these deaths. When she learned of her father's passing, she was not aware that her grandmother had died a year before. Her grief and sense of alienation were that much greater, for she'd had a deep relationship with her grandmother, who taught her calligraphy at the age of five.

"Hills and Water" (2017), by Miran Lee.

Miran Lee also uses fiber in her artwork. For Hills and Water, she worked with Korean silk and ramie which she had collected over a decade. From her mother, she inherited two rolls of 50-year-old ramie, wrapped in old Korean papers containing the name of the person who had woven the cloth. Lee spent two years meticulously hand sewing (unbelievably tiny stitches!) the fabric that had traveled from the east end of Korea, where she's from, to the west end of the United States, where she lives now. Her work reflects an old saying in Korea--"unfamiliar mountains and water"--that describes the feelings of foreignness and homesickness in an unfamiliar place.

Detail of "Hills and Water" (2017), by Miran Lee.

While the blues, greens, and purples are reminiscent of sky and water, the neutral colors reflect rocks and hills--the environment of the San Francisco Bay Area. In using Korean fabrics and sewing techniques from hanbok (traditional clothing) and bojagi (traditional wrapping cloths), Lee has successfully combined aspects of her native country and her adopted country.

Detail of "Hills and Water" (2017), by Miran Lee.

Nicholas Oh made the life-size figure Chinktsugi out of ceramic, wood, resin, and paint. Instead of avoiding the issue of discrimination, he challenges assumptions about Asian Americans, who are regarded as foreigners. According to Oh, the title of his work is a word play on kintsugi, a Japanese method for fixing broken pottery that uses lacquer mixed with gold or silver dust. It highlights cracks and repairs to signify events in the life of the object while simultaneously embracing its flaws. Oh finds similarities between his hyphenated identity and this technique and its underlying philosophy. For example, he says that some people consider his lack of extensive knowledge of Korean culture a flaw. Yet others see him generically as Asian and have no compunctions about hurling insults and slurs at him.

"Chinktsugi" (2017), by Nicholas Oh.

In Chinktsugi, Oh includes motifs from Japanese and Chinese cultures as well, such as an auspicious blue dragon (symbol of strength and fortitude) and Chinese hexagrams and symbols of good fortune (sign of hopefulness). Oh adds that when he tries to make non-Asian cultural references and to comment on other issues through his art, he is often criticized for going outside of his "race."

Detail of "Chinktsugi" (2017), by Nicholas Oh.

In Justice or Else, eight life-size, headless figures, made with ceramic, wood, paint, and patina, are dressed in military garb and hold billy clubs. The impression is one of negativity and menace. While serving in the U.S. Marine Corps, Oh faced racism and ignorant ("headless" or nonthinking) stereotyping. When he moved to the Bay Area to attend college, he observed a diverse mix of different cultures. He met other Asian Americans who were carrying both the heritage of their ancestors and the pride of being part of another place. Inspired by others in San Francisco, he was finally able to truly be himself. Oh's intention in his artwork is to focus on "the fact that social issues in America are real and present. That racism is real, injustice is real, segregation is real and [that] these issues impact all of us, not just one particular group of people."

"Justice or Else" (2015-16), by Nicholas Oh.

There are other works on view by Jung Rang Bae, Sohyung Choi, and Young June Lew. As the exhibit runs until December 10, I hope you'll have an opportunity to visit Mills College in Oakland, CA and see all of them. Independent Curator Linda Inson Choy and Consulting Curator Hyonjoeng Kim Han (Associate Curator of Korean Art, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco) have done a masterful job of hanging the thoroughly contemporary show with a sense of traditional East Asian aesthetics, whose concepts transcend time and place.

For example, because space is as important as form or content, each artist is given ample height and width for her/his work to breathe freely. I especially welcome the overall spaciousness after feeling overwhelmed by shows in the 19th-century French Salon mode, where it seems every square inch of wall space is covered and I don't know where to look. Being able to walk around and under the pieces with ease affords viewers a variety of perspectives. In addition, In-Between Places embodies an elegant simplicity. It is evident in the repetition of shapes and stitches, in the contrast of charcoal and ink on white paper and canvas, in scroll-like drawings, along with other details.

While the artists have inhabited in-between places, the exhibit beautifully demonstrates how it's possible to integrate both cultures through diverse styles, techniques, mediums, and subject matter.

Questions and Comments:

Based on your own experience or the experiences of people you know, what are the challenges that immigrant artists confront?

How can we honor our cultural heritage while also embracing the one we live in?

How has art changed your mind about sociopolitical issues?

How do you address such issues in your own artwork?