Strokes and Splashes of Ink

Recently I made a long overdue trip to Stanford University. Because several decades have flown by since I attended graduate school there, I hardly recognized the place. And I had no recollection of the art museum that was my destination to see Ink Worlds: Contemporary Chinese Painting before it closed on September 3 at the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts.

The Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University.

I've dabbled only a bit in ink painting/calligraphy (I'm taking another workshop next weekend). I'm drawn to the minimalism of black and white and find the traditional confinement to grayscale both intriguing and serene. Richly black ink strokes and swirls come across as bold and energetic. In Western art traditions, color is essential in capturing scenes in nature, but in the history of East Asian ink painting, artists can create the most evocative landscapes as well as abstraction using only a range of shades along a continuum from black to white.

Months before I went to Stanford, the following words by Korean art critic Jeung Biong-Kwan helped me to understand this difference:

Ink paintings are confined by the paper, brush and ink initially employed in calligraphy. The rejection of color by great literati painters such as Su Tung-p’o, Shih-tao and Mi Fu also played a part in determining that the use of color was a futile attempt to imitate nature. This attitude still prevails in the world of ink painting.

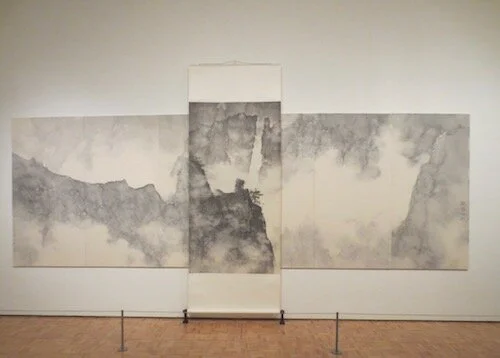

"Dragons Amidst Mountain Ridge" (2006-9), by Li Huayi. Ink on paper. A set of six panels overlaid with a hanging scroll.

In the gallery, I learned that Ink Worlds includes two dozen artists that embrace pioneers of ink abstraction from the late 1960s to visionary imaginations of celestial realms in the current decade. They have had training and careers based in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the U.S., and Europe. It's clear to me that the diversity of their ink painting and calligraphy simultaneously recalls ancient Chinese art and reflects the unfolding of modern art since the 20th century. According to the curators, these artists deploy "new media, innovative formats, and experiments in ink technique and application." They're also pushing into new thematic arenas and adding colors. What made the exhibit especially interesting for me is this integration of ancient and modern, inspiration from the past transformed in the present. While I have no intention of imitating Chinese ink painting, I can be inspired by geometric shapes as well as graceful, dancing lines to create my own work.

Ink Worlds at The Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University.

Because not everyone has had access to this show, I decided to share some of it here. However, in this case, as in many others, the presence of large-scale artwork, especially the sense of panorama, and the space where it's hung, isn't necessarily conveyed well through photos. That said, I offer at least a glimpse. Instead of strolling through the gallery, you're scrolling online!

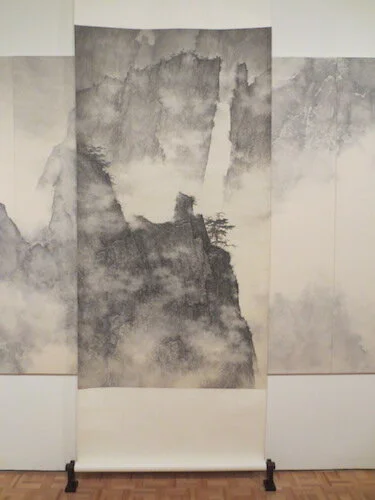

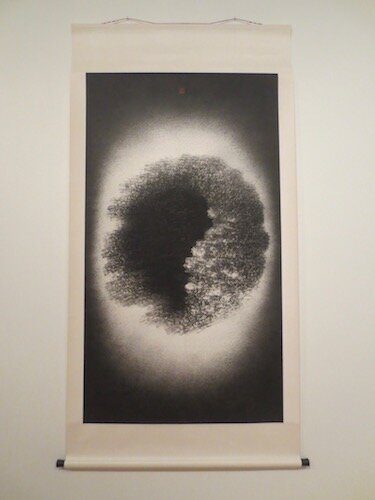

Scroll in "Dragons Amidst Mountain Ridge" (2006-9), by Li Huayi.

The two images above of Li Huayi's "Dragons Amidst Mountain Ridge" are an example of this issue of experiencing art differently in person. The set of six panels is overlaid with a hanging scroll. Beneath the scroll is a hidden region in which a dragon exists, though it is invisible to our eyes. The landscape is composed of texture strokes applied to amorphous shapes that resulted from splashing ink onto paper. Li Huayi was inspired by a 13th-century handscroll portraying nine dragons.

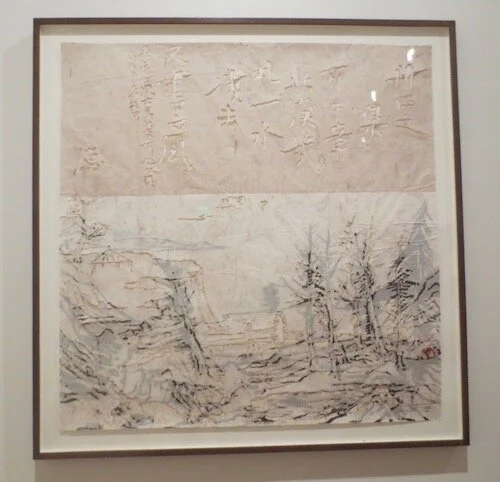

"Landscape" (2007), by Wang Tiande. Ink on paper, with burns.

Wang Tiande is based in Shanghai. While he draws inspiration from 14th-century painter Ni Zan's barren landscapes, he also creates voids by burning forms of mountains, trees, and characters onto rice paper, revealing an underlying ink landscape.

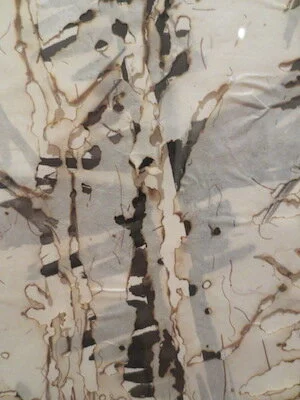

Detail of Wang Tiande's "Landscape" (2007).

One of the artists in the exhibit has been living in the San Francisco Bay Area for more than 30 years. Zheng Chongbin's "New Six Canons" is a painterly translation of a 6th-century art theoretical text about painting by Xie He. The curators explain this hexaptych as a reversal of the hierarchy between the verbal and the visual. Instead of attempting to recover what was lost in translation, the artist expanded the possibilities of Chinese painting by creating swaths of completely inked and wrinkled paper painted with acrylic.

"New Six Canons" (2012), by Zheng Chongbin. Ink and acrylic on paper.

Detail of "New Six Canons" (2012) by Zheng Chongbin.

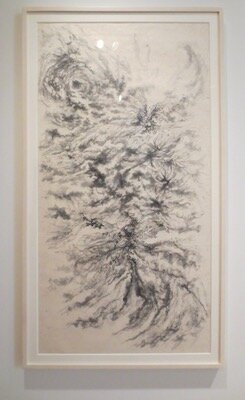

Zhang Yu's untitled painting transports me to outer space, where we know stars explode in a brilliant burst of light.

"Untitled" (1996), by Zhang Yu. Ink on paper.

Irene Chou adds color to her exuberant ink painting.

"Untitled" (1995), by Irene Chou. Ink and color on paper.

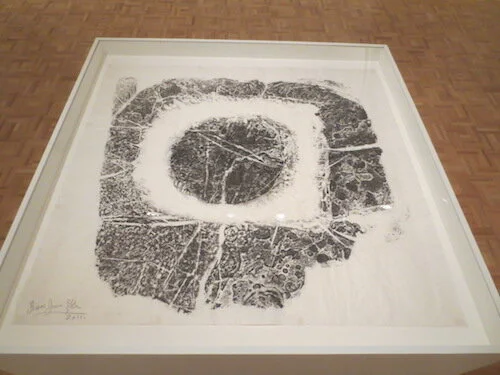

"Rubbing Sun" is, like the others, ink on paper, but was created in a different step-by-step process. Zhang Jian-jun was inspired by a statement in the Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven from c. 100 BCE: "The square pertains to Earth, and the circle pertains to Heaven. Heaven is a circle, and Earth is a square." First, the artist chiseled a large stone, quarried from Lingbi County in China's Anhui Province, where the raw materials for inkstones are found. Then he lay a wet piece of paper across the stone and tamped into its carved crevices. Ink was tapped into the entire surface, resulting in a black-and-white image.

"Rubbing Sun" (2011), by Zhang Jian-jun. Ink on paper.

Collage fans will appreciate what Zhen Chongbin did in "Merged with Variant Geometries." He overlapped folded and torn paper fragments and overlaid them with ink and white acrylic paint. Angles and straight edges form fragments of an imaginary landscape that competes with geometric shapes.

"Merged with Variant Geometries" (2017), by Zheng Chongbin. Ink and acrylic on paper, mounted on aluminum.

Detail of "Merged with Variant Geometries" (2017), by Zheng Chongbin

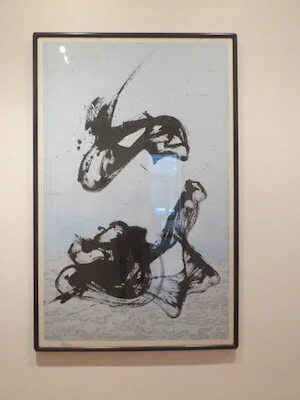

And then there are the dense, dynamic and spontaneous coils of black ink made by Qin Feng in "Civilization Landscape #1" and the dance-like strokes in "Desire Scenery No. 1." The artist sometimes creates his ink paintings standing up, using massive handmade "brushes" fashioned from mops that he sweeps choreographically over the paper on the floor.

"Civilization Landscape #1" (2003), by Qin Feng. Ink on paper.

"Desire Scenery No. 1" ( (2007), by Qin Feng. Ink on paper.

Arnold Chang, born in the U.S., swirls ink into wisps and tendrils that, in my imagination, become plant matter floating beneath the water's surface.

"Mindscape" (2011), by Arnold Chang. Ink on paper.

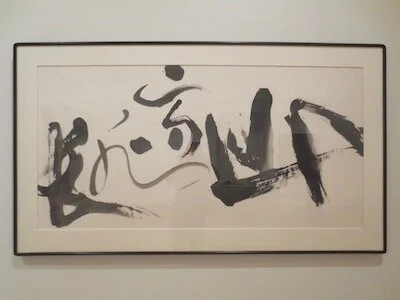

According to the title card, Tong Yangtze is an advocate of classical Chinese philosophy who draws inspiration from moral and philosophical texts. In "Mountains High, Waters Long," which reads from right to left, she quotes a phrase from a Tang dynasty poem that symbolizes a person's profound character of nobility. The word forms are distorted, suggesting instead a quasi-landscape.

"Mountains High, Waters Long" (1995), by Ton Yangtze. Ink on paper.

Before going to the exhibit, I watched a series of videos about contemporary Chinese artists through Kanopy kanopy.com/product/enduring-passion-ink. One of them is of Xu Bing creating landscape elements with Chinese pictographs, particularly the root characters for "mountain," "river," "tree," and "rock." If you can't access that video, another short one will give you at least an idea of how Xu Bing uses language symbols in painting a scene. youtube.com/watch?v=b7THiXjQv3A

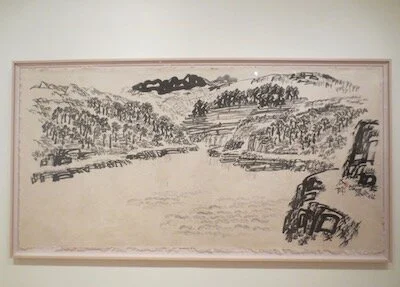

"Landscript" (2002), by Xu Bing. Ink on paper.

A scholar of Chinese language and literature, Wang Fangyu (1913-1997) wrote about deciphering Chinese cursive and ancient seal scripts. (I'm particularly fond of the latter after seeing them in Korea.) In his calligraphic works, he does not make a recognizable Chinese character but an invented form that consists of familiar strokes and structural parts of characters.

"Puzzle" (1986), by Wang Fangyu. Ink on paper.

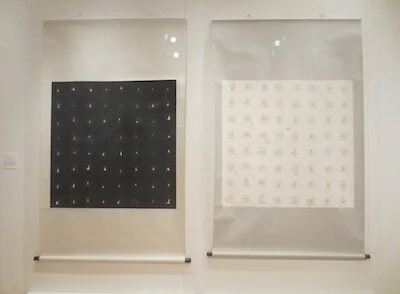

Although I have not covered the entire exhibit, I'm going to end here with a novel way of presenting the Buddhist text the Heart Sutra, (The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom) in two different scrolls. Fung Mingchip edited the text to fit a square composition, executing the characters in "Light Script" with pale ink and "Dark Script" with water. In the dark one, the characters appear only as ghostlike traces where the ink did not penetrate the paper. His intention is to reflect the sutra's idea of form and emptiness being equivalent.

"Heart Sūtra: Light Script/Dark Script" (2005), by Fung Mingchip. Ink on paper.

Questions and Comments:

Do you ever paint with ink? If so, what kinds of paintings are they: calligraphic strokes? abstract landscapes? geometric abstractions?

What do you find inspirational in the contemporary Chinese painting? If you don't, what dis-attracts you? Do you find it too limiting to work only with grayscale? Do you prefer literal/realistic images?