They Love Me, They Love Me Not

Who doesn’t rejoice upon hearing one’s creations called “beautiful,” “brilliant”, “moving”, “exciting,” “stunning,” “extraordinary”? Or maybe you’d prefer “provocative,” “stimulating,” “breaking new ground,” “a tour de force.” Unless you’re a hard-bitten cynic or you sense that the praise is false, don’t those compliments make you feel good, especially when you’ve worked so hard to bring forth your vision on paper, in paint or marble, with words, textiles or clay?

Source: lifehacker.com/

But what happens when you get a thumbs down instead, and your drawing, dance, play, or poetry is roundly criticized rather than regaled? Does your ego deflate like a balloon? Are you able to keep creating? What do critics even know about the roller-coaster process an artist goes through? And what do we, as viewers, know about what went into making a work of art that seems utterly accomplished? When do we accept criticism that could be useful and when do we ignore it and trust our own instincts? How do we make validation an internal affair and believe in ourselves?

Source: penguinrandomhouse.com/

After I finished reading a novel based on artists’ relationships—particularly between Edgar Degas (1834-1917) and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926)—during La Belle Époque in Paris, I found myself pondering these questions. In Robin Oliveira’s I Always Loved You, Cassatt considers Degas a mentor of sorts. When she asks him, “Do you believe that talent is a gift…bestowed…on some artists and not on others?” he responds that it’s rubbish:

Art does not arise from a well of imaginary skill, obtained by dint of native ability. The sublime is a result of discipline. Art is earned by hard work, by the study of form, by obsessive revision. Only then are you set free. Only then can you see.

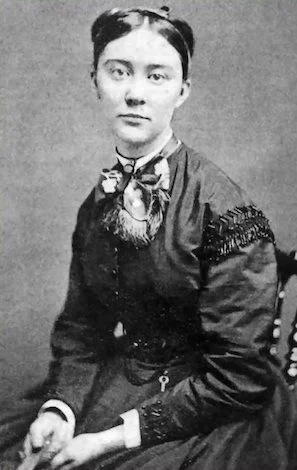

Mary Cassatt. Source: mydailyartdisplay.wordpress.com/ 2014/03/25/

When Cassatt tells him his art looks effortless, Degas gets heated:

Effortless? What do you think? That this is easy for me? That I could decide to paint something and then it magically appears from my hand? That I have some gift, that my work arrives finished, that this is not a struggle for me?….Every day I awake and wonder how I’m going to get through the day. I have to draw and redraw endless lines upon endless lines, tracing within grids to get the perspective right, to perfect the proportions, to establish the composition. And even then I get it wrong. I have nothing of talent. I have only desire and dogged work. I doubt myself every moment.

Edgar Degas. Source: wikipedia.org/

Yet, sometimes, a poem unexpectedly arrives out of the ether and is captured in its entirety, as American poet Mary Oliver, who died on January 17, noted in an interview. Or a symphony is heard within one’s head and the task is simply to mark down the notes. Mostly, though, as Degas asserts in the novel, practice and revision are called for.

Mary Oliver. Source: goodreads.com/

Later in the narrative of I Always Loved You, Cassatt experiences “the exquisite terror of beginning” flooding through her as an idea forms in her mind. Because it was more ambitious and complex than anything she had previously attempted, the challenge paralyzed her at times.

Was the painting as good as she thought it was? She disciplined herself not to answer, for her opinion of her work, rooted as it was in emotion, was unreliable in the vulnerable gulf of time between what she wanted the canvas to be and what it currently was.…The effort of spurning the ugly voice [of her doubting mind] exhausted her, and only when she was certain it had quieted down did she turn to study the canvas….

“Summertime” (1894), by Mary Cassatt.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Despite her commitment, in hours and hours of sustained work, Cassatt was devastated by awful reviews of her first exhibit. When her father observed how much the negative criticism affected her, he told her to stop wallowing in self-pity. It’s advice any of us could heed, whether in art or other situations:

If you are going to abandon your work because someone speaks ill of it, then it has never really been your work, has it? It becomes theirs. You give it up. Do you want to do that? Your work is different; you declare it so; you want it to be so. But you cannot expect the world to understand when you ask them to look at work that is different than what they are used to seeing. The human mind is not equipped to adapt too rapidly. People have been told for so long what is good by the École des Beaux Arts that when something new comes along, they cannot adjust their thinking. Your work doesn’t look anything like what they have been told is good. Ergo, your pictures must be bad. It’s confused logic, but logic nonetheless. And it will alter with time. You must give it time. Why yield your confidence to a bunch of jackals?

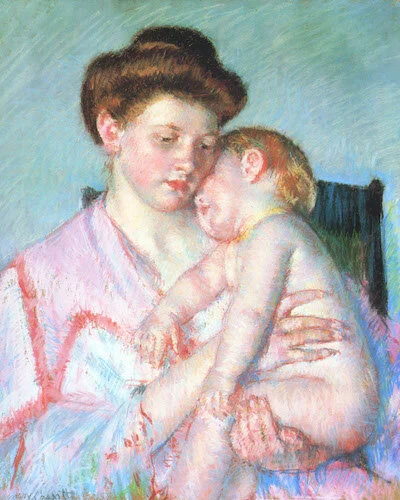

“Sleepy Baby” (1910), by Mary Cassatt.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Cassatt does get over her wallowing and works toward another exhibit, where she experiences the complete opposite, receiving heaps of praise and selling everything. Yet that, too, proves difficult. She tells her father, “It’s too much pudding.” He counters by reminding her of what happened previously.

The last time you received bad news, we had to resuscitate you. Now you are lauded in every review, are celebrated…and you say the praise is too much. I will never understand you.

Her response? That he doesn’t understand because he’s not an artist.

”In the Box” (ca. 1879), by Mary Cassatt. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

I can relate to that, especially when faced with someone who is insists on reason and logic rather than accepting the vagaries of emotion. But Cassatt’s father certainly makes a point to consider. Is it possible to get on an even keel as a creative person? Can we ride the big waves that threaten to overturn us? Can we be satisfied with a becalmed sea? I’ve watched my mind when my work has been accepted into a show or rejected. Sometimes it feels easier to deal with and sometimes it doesn’t. It’s like being on a teeter-totter.

Each of us experiences criticism in our own way, so the tips that abound on the internet vary. For example, there’s the option of evaluating what a person has said before deciding whether to apply it or not. Are the comments constructive or simply mean-spirited? While we’re advised not to take criticism personally, that’s not necessarily how we react. I think that’s because we get so identified with what we’ve written or painted or composed. However, I have come to realize that the situation is rarely, if ever, a case of “love me, love me not.” It’s about the work, even though we created it, and it’s certainly not going to appeal to everyone. And, no matter how good our work may be, there will be detractors, whatever their personal agendas.

Source: penguinrandomhouse.com/

Reading Michelle Obama’s memoir, Becoming, I came across a valuable perspective she gained from meeting “all sorts of extraordinary and accomplished people—world leaders, inventors, musicians, astronauts, athletes, professors, entrepreneurs, artists and writers, pioneering doctors and researchers.”

All of them have had doubters. Some continue to have roaring, stadium-sized collections of critics and naysayers who will shout I told you so at every little misstep or mistake. The noise doesn’t go away, but the most successful people I know have figured out how to live with it, to lean on the people who believe in them, and to push onward with their goals.

Questions and Comments:

How do you deal with criticism, with acceptance or rejection of your work?

What advice can you offer to artists of all kinds who feel devastated by negative reviews? What keeps you going?