Art + Science, A Match Made in Heaven?

When I attended university, the humanities were considered one separate area of study and the sciences another. In my art history and literature classes, no one talked about how the different disciplines affect each other. When we discussed artists, we didn’t discuss scientists. Neither was art discussed in science classes. Yet, if we examine the lives of creative types, we find a strong link between the arts and sciences, one that shouldn’t surprise us, since both call for imagination and originality. They inform each other in subtle as well as obvious ways.

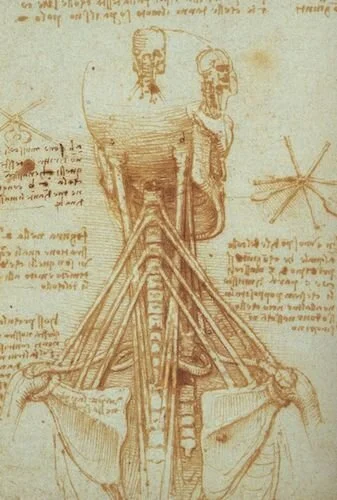

Leonardo da Vinci is a perfect example. Considered one of the greatest artists of all time, he kept a daily journal (13, 000 pages) that included scientific observations and illustrations of the world around him, inventions, studies of emotions and movement, and more.

“Anatomy of human neck” (c.1515), by Leonardo da Vinci. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Several hundred years later, as scientific and artistic changes exploded , the first half of the 20th century provided new inspiration for new art. An exhibit that I managed to catch before it closes this weekend illuminates the connections that were made.

Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) derives its title from the Dimensionist Manifesto. This 1936 proclamation called for an artistic response to the era’s scientific discoveries and was signed by, among others, Hans and Sophie Arp, Francis Picabia, Wassily Kandinsky, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp. It was also endorsed by Ben Nicholson, Alexander Calder, László Moholy-Nagy as well as artists with whom I am not familiar. Interestingly, the works on display are by many artists I recognize—such as Barbara Hepworth, Isamu Noguchi, and Pablo Picasso—but which I don’t recall ever seeing before.

[Apology: I had to take the photos at an angle to avoid my reflection in the glass.]

“Project for Wood and Strings, Trezion II" (1959), by Barbara Hepworth. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College.

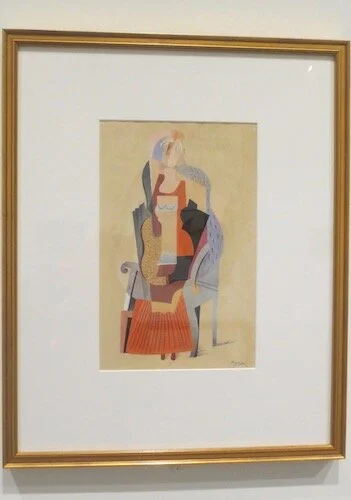

“Young Girl in an Armchair” (1917), by Pablo Picasso. Gouache and black ink over graphite on wove paper. Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY.

While I don’t generally consider artwork within a context of science—how many of us do?—the explanatory title cards opened my eyes to appreciate the paintings, sculptures, and photographs from an expanded perspective.

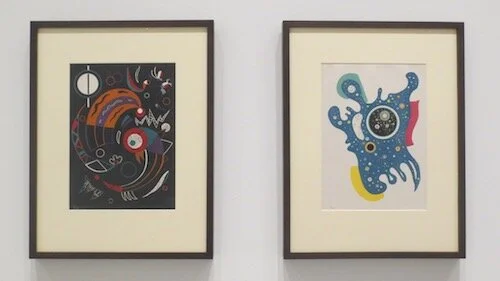

Take the appearance of biomorphic objects in art, a result of being able to discern life forms through more powerful microscopes. This technical development revealed an entirely new microworld in which materiality is more void than solid: cellular structures, aquatic life, and the atomic makeup of matter. It allowed not only scientists but also artists to imagine what was invisible to the naked eye. Russian-born painter and art theorist Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) was one of them. He “cited the importance of the microscope in his abstract creations and made many close studies of microbial forms.”

[the following image is not in the exhibit, but the double one after it is]

“Pointille” (1935), gouache on black card, by Wassily Kandinsky. Source: www.sothebys.com/

“Kometen” (1938) and “Sterne” (1938), color lithographs, by Wassily Kandinsky. Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

Swiss-born Herbert Matter (1907-1984) actually used microscopic lenses to photograph an amoeba. Had I not read the information next to the image, I’d have thought this was abstract art rendered without a camera.

“Amoeba Forms”(1937), gelatin silver print, by Herbert Matter. Stanford University Libraries.

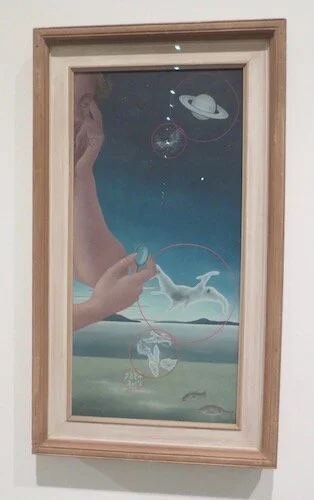

During a two-semester biology course at a Pasadena college, Helen Lundeberg (1908-1999) drew cellular and embryonic forms that she observed under a microscope. They later showed up in her paintings as a reflection of an interconnected vision of the universe.

“Microcosm and Macrocosm” (1937), oil on masonite, by Helen Lundeberg. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

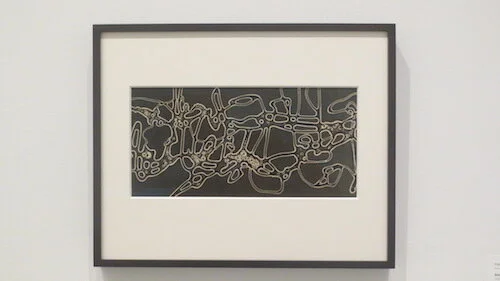

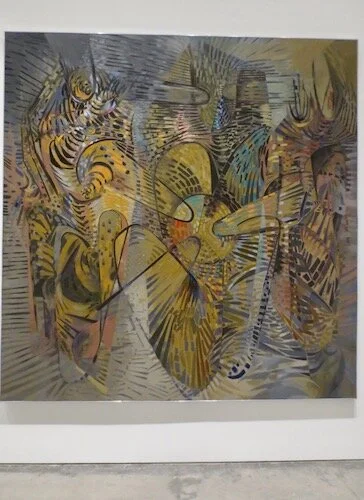

The title card for Membrane, No. 239, by Gerome Kamrowski (1914-2004), indicates that this American artist was familiar with “the mathematical patterns found in nature ranging from microscopic cells to mollusk shells” and leaves and he also visited the American Museum of Natural History in New York to study such natural forms.

“Membrane, No. 239,” oil and pastel on canvas, by Gerome Kamrowski (1942-43). Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

According to the card for Henry Moore’s (1898-1986) bronze sculpture Stringed Figure, the British artist acknowledged that the telescope and microscope influenced his curved, biomorphic forms. He disliked “the idea that contemporary art is an escape from life” because it doesn’t aim at reproducing a natural look. He suggested, instead, that “it may be penetrating into reality.” I found this observation especially appealing because I have a preference for abstract art and its ability to convey or evoke the complete spectrum of emotions and ideas without mimesis.

“Stringed Figure,“ designed by Henry Moore in 1938 and cast in bronze in 1960. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College.

Advances in physics and astronomy also affected the thoughts and creations of artists with respect to the cosmos. There was a different way of looking at matter and energy, at time-space, a fourth dimension; there was quantum mechanics. There were theories that challenged the concreteness of beliefs held dear for so long.

Austrian-born Wolfgang Paalen (1905-1959) avidly read Matter and Light by French physicist Louis de Broglie, which positioned the subatomic universe as the driving force of nature. It led to his new cosmic imagery.

“Les Cosmogones” (1944), oil on canvas, by Wolfgang Paalen. Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco.

Detail of “Les Cosmogones” (1944), by Wolfgang Paalen. Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco.

“E = mc2” (1944), papier-mâché, and “Bucky” (1943), wood, wire, by Isamu Noguchi. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, Long Island, NY.

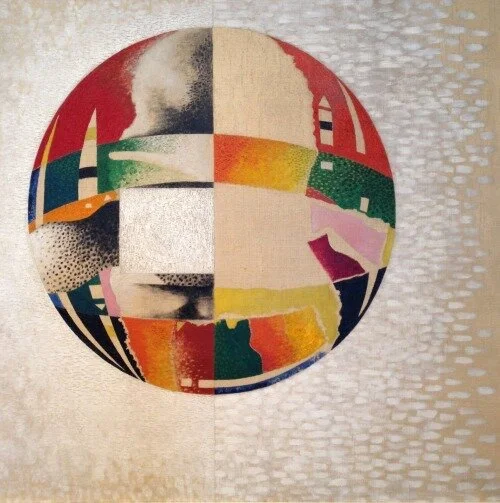

Just looking at Marcel Duchamp’s (1887-1968) work Rotoreliefs, I found it hard to discern his intention. Reading the card, I learned that the flat, two-dimensional disc with a spiral design appears, when set in motion, to transport into a wobbly three-dimensional cylinder that moves in four-dimensional space-time. I still didn’t get it, but here’s a photo.

Rotoreliefs [Optical Disks] (1935), by Marcel Duchamp.. Discs printed on each side in offset color lithography. Yale University Art Gallery.

Pevsner’s spiral construction breaks away from a single point of perspective and incorporates voids, meeting the goal of the Dimensionist Manifesto by “stepping out of closed, immobile forms (…conceived of in Euclidean space), in order to appropriate…four-dimensional space,” open to inner space and then to movement. Today, we take for granted such sculptures, but juxtaposed with classical solid sculptures that were the norm for centuries, they interrupt traditional standards. Artists have continued to work with so-called negative space and scientific progress.

“Black Lily” (1943), bronze, by Antoine Pevsner. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

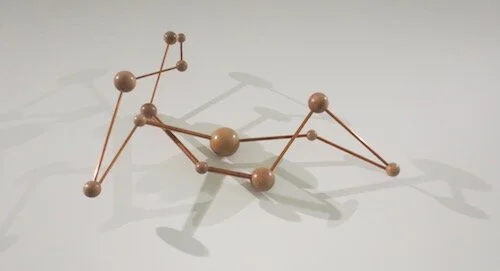

“Reclining Molecule” (2013), by P. Koshland. Wooden balls and metal rods. BAMPFA.

My favorite work in the exhibit, the one I sat down on a bench to gaze at, is by Hungarian-born painter, photographer, and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946). Nuclear II might seem like an odd title for what I consider an appealing painting for its shapes, colors, and textures. However, closer examination discloses something ominous: a sense of rupture rather than one of unity or interconnectedness. This is the second of two paintings Moholy-Nagy created in response to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Whereas previously he had drawn on a positive view of modern physics, this radical departure in his artwork references the potential and real danger of harnessing nuclear power.

“Nuclear II” (1946), oil on canvas, by László Moholy-Nagy. Milwaukee Art Museum. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

The exhibit at BAMPFA made me reconsider how a historical framework can help anyone better understand and admire artistic engagement with the world of science. None of us creates in a vacuum. Our art emerges out of the contexts—be they social, political, spiritual—of our times, whether we recognize and acknowledge them or not.

And what about scientists being influenced by the arts? The exhibit doesn’t address this question, so I’m eager to learn about scientists who feel that the arts have had an impact on their métier. In looking for clues about Albert Einstein’s influence, I came across a note I had read years ago. Like some other famous scientists, his thought patterns were highly visual. Maybe that’s why he said: “I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination” and “The greatest scientists are artists as well.”

I’m grateful that both artists and scientists struggle to view and comprehend the universe in new ways, and then to communicate that to the rest of us. It enables us to see and make sense of the cosmos differently as well. What we knew to be true is transformed, and there’s no path back to outmoded thinking.

Questions and Comments:

How has science affected your own creativity?

What particular discoveries or theories have had the greatest influence on your thinking and thus on your work?

If you’re a scientist, how do the arts affect you directly or indirectly?