Light as Art

Winter Solstice at Stonehenge.

Source: https://historiazine.com/o-que-%C3%A9-stonehenge-41aa4aa8941b

As we approach the shortest stretch of daylight of the year, it seems an appropriate time to take a brief look at art's evolving relationship with something so intangible yet so evident and compelling--light. In the process of reading about it and having some of my own experiences, I couldn't help but expand my thinking about what constitutes art.

Generally, when I think of light in art, certain artists and their paintings come to mind: to be specific, Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). Maybe, for you, it's the Italian painter Caravaggio (1571-1610) or any number of other master artists who have used light to advantage in their portraits and landscapes.

"The Philosopher in Meditation" (1632), by Rembrandt van Rijn. The Louvre, Paris.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

"Chichester Canal" (c. 1828), by J.M.W.Turner. Tate, London.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

"Lydia Leaning on Her Arms, Seated in a Loge" (1879), by Mary Cassatt. Collection of Mrs. William Coxe Wright, St. Davids, PA. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

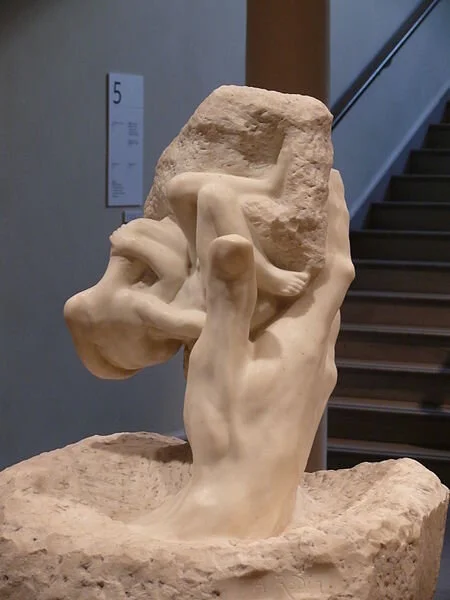

"The Hand of God" (1898; 1917), by August Rodin. Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org

All those artists of long ago endeavored to capture light with paint and even with gleaming marble. Eventually, photography was born and impressions of light were imprinted on film. It was not until the 20th century that artists actually used light itself as the medium of expression. In doing so, they questioned the fundamental ground of traditional art.

There was a shift from material form to immateriality, from tangible object to perception. This kind of art was not reproducible as a poster; it had to be experienced in person. As American artist Robert Irwin (b. 1928) has said about his work, it is not an object but site-conditional. You have to be there to perceive it. [For an interview with Irwin: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JCh8s10f2ws]

"Scrim Veil—Black Rectangle—Natural Light" (1977), by Robert Irwin. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

"Light and Space" (2007), by Robert Irwin. Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego. Photo by Philipp Scholz Rittermann.

Source: http://www.mcasd.org/exhibitions/robert-irwin-light-and-space

There were artists in Europe who experimented with light in earlier decades, but Irwin, along with James Turrell, Peter Alexander, Larry Bell, Craig Kauffman, Ron Cooper, Mary Corse, Fred Eversley, Bruce Nauman, Maria Nordman, Helen Pashgian, DeWain Valentine, Doug Wheeler, and John McCracken, became associated with the Light and Space Movement that originated in Southern California in the 1960s. Instead of creating art on a canvas, they worked with glass, neon, fluorescent lights, and resin. Their art focused on an experience of light and other sensory phenomena. They did this by orienting the flow of natural light, placing artificial light inside objects or architecture, or using transparent, translucent and reflective materials to play with light.

"Untitled" (1968), by Helen Pashgian. Cast polyester resin. Photo by Joshua White.

Source: http://davidtotah.com/artists/helen-pashgian/

Although Marina Abramović (b. 1946) is a Serbian performance artist rather than an artist manipulating light, as a teenager, she realized that process and experience were more important than a resulting object. One day, she was lying on the grass staring up at a cloudless sky when she noticed twelve military jets leaving white trails behind them. She recalls: I watched in fascination as the trails slowly disappeared and the sky once more became a perfect blue. All at once it occurred to me--why paint? Why should I limit myself to two dimensions when I could make art from anything at all: fire, water, the human body? Anything!

Having grown up viewing classical art, I didn't think that you could make art with water (except in watercolors) until I saw a film of Andy Goldsworthy's ephemeral works. Neither did it occur to me that you could create art experiences with light.

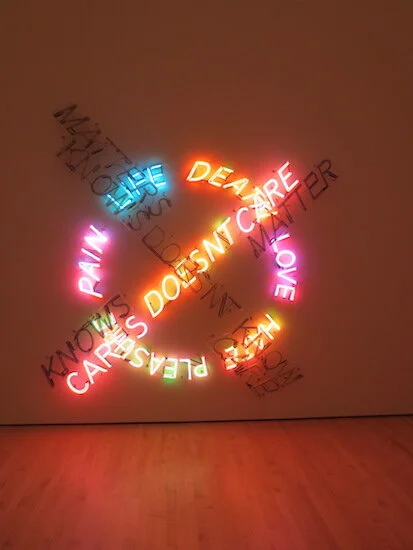

"Life Death/Knows Doesn't Know" (1983), by Bruce Nauman. Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.

Over the years, I have seen "light" art, but I confess to not recognizing it as such. I wondered what it was, especially when I was looking at a series of words in neon, which I had been accustomed to identifying as a commercial sign. What I didn't know was that artists like Bruce Nauman were using neon signage to subvert our expectations of it. For example, he replaced the banal vocabulary of commercial advertising with such contradictory terms as life/death, pleasure/pain, love/hate and intersected them with sentence fragments. The light cast by the neon creates more than the words by encompassing the walls as well.

"An Accidental Color" (2012), by Toyohisa Shizo. The Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul.

Then I stepped into an elevator at a museum in Seoul in 2015. The doors closed and suddenly I was enveloped in hot pink light. This installation was produced by Japanese designer Toyohisa Shozo, who blends lighting and architecture. Coordinated with the movement of the elevator, the light inside changes colors every hour from red, blue and green to yellow, causing an effect of accidental colors. Actually, they are not authentic colors but are imagined because of a false perception by the brain.

Outside James Turrell's installations at The Museum San.

During another visit to South Korea in 2016, I went to The Museum SAN in the mountains of Wonju. Designed by Japanese architect Tadao Ando, it includes, in addition to outdoor sculpture gardens and indoor exhibits, a building dedicated exclusively to the art of James Turrell (b. 1943), whose installations celebrate the optical and emotional effects of luminosity.

Being inside the installations was unlike anything I'd ever experienced, except perhaps in altered states arising from deep meditation and certain substances. Photographs cannot adequately convey what our senses tell us while sitting in or walking through the different spaces. These light works are not at all like standing in front of a painting or a sculpture. It is a total immersion in light and how it affects our various sensory systems.

"Skyspace. Twilight Resplendence" (2012), by James Turrell. The Museum San, Oak Valley, Wonju, South Korea.

Source: http://www.museumsan.org

The Skyspace is an observatory for quiet and contemplation. Colored lights illuminate the walls, thus affecting how we see the sky through the openings.

"Horizon Room. Lost Horizon" (2012), by James Turrell. The Museum San, Oak Valley, Wonju, South Korea. Source: http://www.museumsan.org

The Horizon Room affords the opportunity to sense two- and three-dimensional planes while running across the stairs.

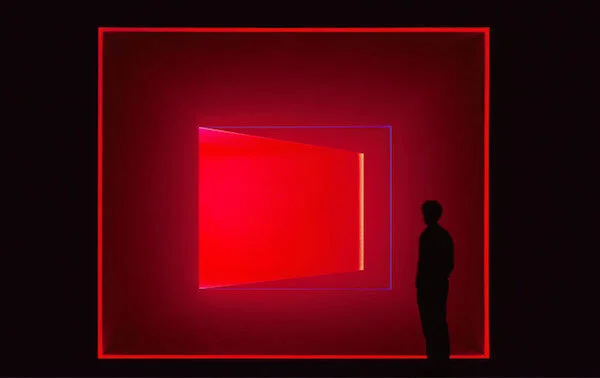

"Wedgework, Cimarron" (2014), by James Turrell. The Museum San, Oak Valley, Wonju, South Korea. Source: http://www.museumsan.org

The Wedgework frames light to give us a sense of how light shapes our understanding of space. It seems as if there are partitions and screens, but they are simply made of light.

"Ganzfeld, Amdo" (2013), by James Turrell. The Museum San, Oak Valley, Wonju, South Korea. Source: http://www.museumsan.org

In Ganzfeld ("complete field"), a chamber filled with lights, I felt disoriented, not knowing where the floor or walls ended. Did that apparent edge lead to a drop-off or did I simply perceive that it would? Was the space as large as it seemed? The visceral sensation of being in that room was disconcerting.

It's not that light art suddenly made me aware of the unreliability of perception as an accurate experience of reality. It did, however, reinforce that what we see isn't always necessarily what's there or not there. Our perception is colored by so many factors. Yet rationalists believe there is an objective reality. For me, light art suggests otherwise.

Next time I visit the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco, I'll go back to the gallery where the light art of Dan Flavin (1933-1996) is located. Rather than walk by and dismiss it, I'll stop to pay attention to what I'm perceiving. I want to be open to a different kind of art experience than what I'm comfortable with.

"Untitled (to Barnett Newman) two" (1971), by Dan Flavin. Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.

Questions and Comments:

What light art have you experienced and how did it affect you?

How do you use light in your art?