Translating Tradition into Contemporary Art

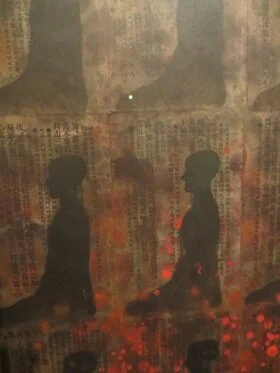

Detail from "Meditation" (1990), by Yoong Bae. Ink and colors on printed paper. Asian Art Museum.

I am fascinated by how artists translate traditions from a long-ago world to our world today. What is the process of transforming aspects of so-called folk art into contemporary art? Who does it, why, and how?

I see this movement from the old to the new almost anywhere I look. Turning bed quilting into quilt art is a good example of changing what many people considered simply utilitarian into something that hangs on a museum wall.

Unexpectedly, other instances popped up last weekend when I visited the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. My main reason for going was to attend the first of a series of lectures sponsored by the Society for Asian Art, "From Monet to Ai Weiwei: How We Got Here." I went with the intention of satisfying my curiosity about the historical transition to modern art in Asia. Each week, for 10 weeks, the focus is on a different region--Japan, India, China, Vietnam and Cambodia, etc. I was disappointed that the initial overview didn't answer my questions, but perhaps other presentations will.

However, the long drive to the city wasn't wasted. While at the museum, I was able to visit new exhibits and enjoy a delightful day with a friend who is a fellow textile artist. I was surprised when one of the new shows, "Mother-of-Pearl Lacquerware from Korea," spoke to my interest in innovating contemporary art from a traditional craft. I'd have never guessed that mother-of-pearl lacquerware would be an inspiration for artists now. First, some images of the traditional work.

Table with birds and trees motif, 1700-1800. (Joseon dynasty, 1392-1910). Lacquered wood with inlaid mother-of-pearl. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Two-tiered chest with stand, 1800-1850 (Joseon dynasty, 1392-1910). Lacquered

wood with inlaid mother-of-pearl and metal fittings. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

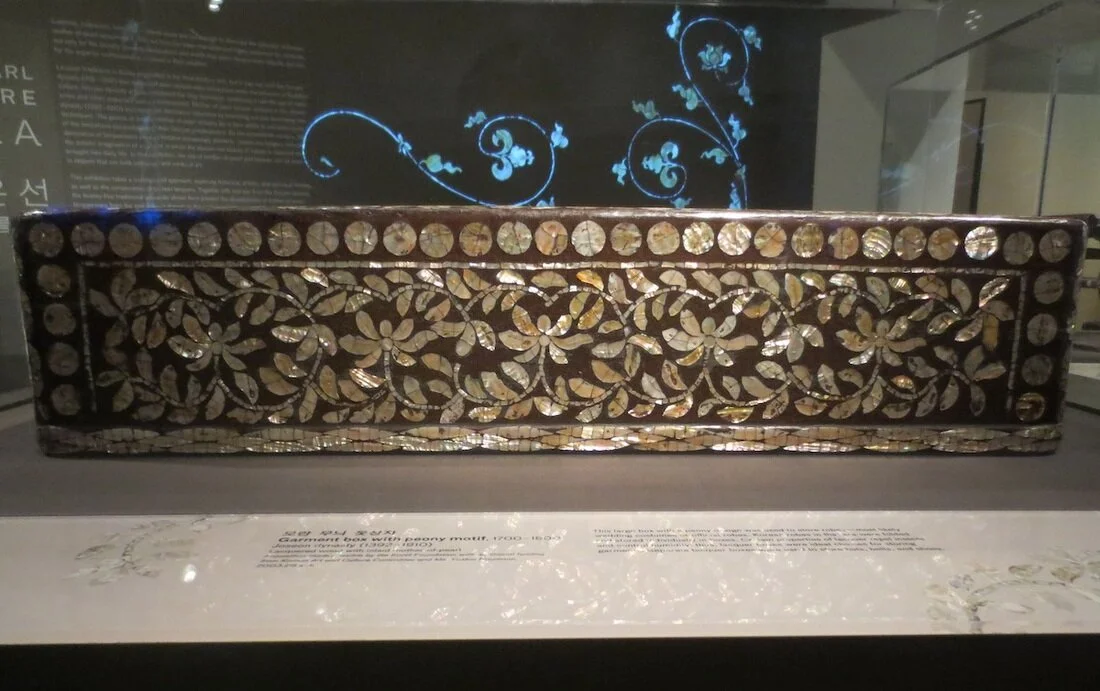

Garment box with peony motif, 1700-1800 (Joseon dynasty, 1392-1910). Lacquered wood with inlaid mother-of-pearl. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

What follows are contemporary mother-of-pearl artworks: Quite a difference, yet using the same materials and techniques that Korean artisans have employed for 1,000 years.

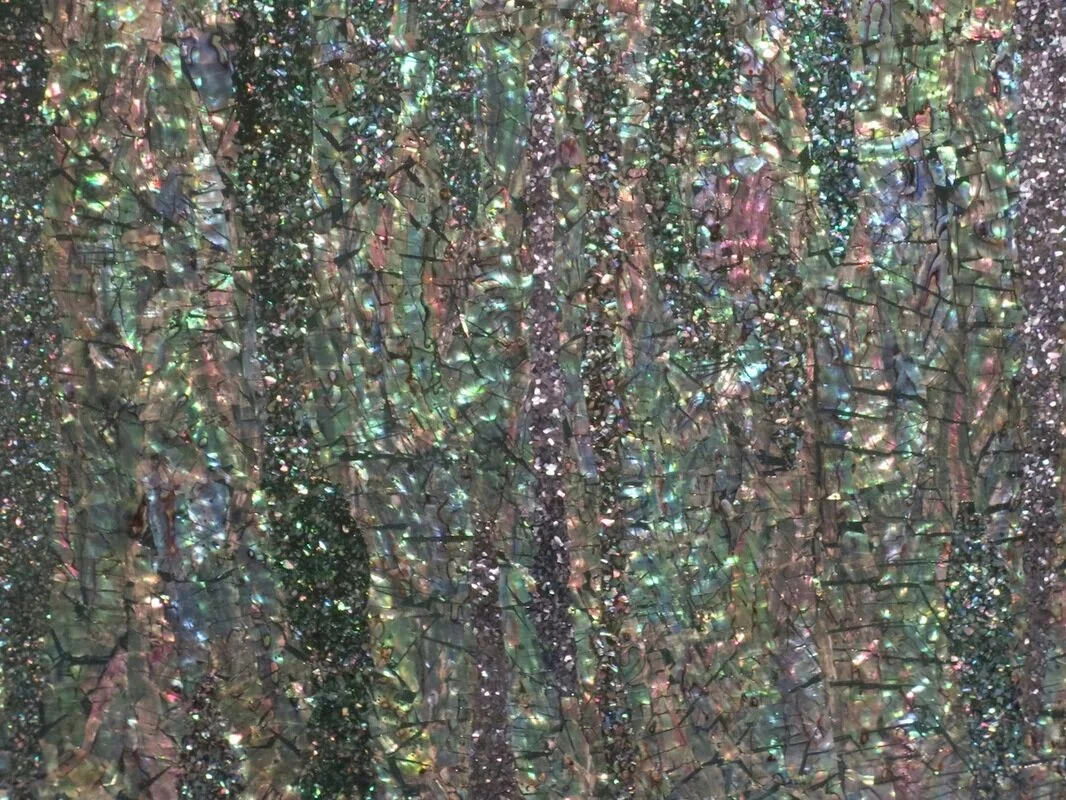

"1880-Summer-Forest-Gogh Series" (2007), by Kim Yousun. On loan from the National Museum

of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

Born in Korea in 1967, Kim Yousun learned traditional mother-of-pearl craft techniques on her own. Then, beginning in the 1990s, she began to use mother-of-pearl as her principal medium with which to create her art. She doesn't see it as a material for craft but as a picture plane, a flat surface that allows her to shift between two-dimensional and three-dimensional perspectives because mother-of-pearl produces different lights and hues, depending on the angle from which one views it.

According to the title card, a trip to a forest inspired Kim Yousun to create "1880-Summer-Forest-Gogh Series." A huge admirer of Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), she found herself standing among the trees, observing sunlight through them. She wanted to capture the specific moment of her subjective experience of energy and light and recreate it with innumerable mother-of-pearl pieces.

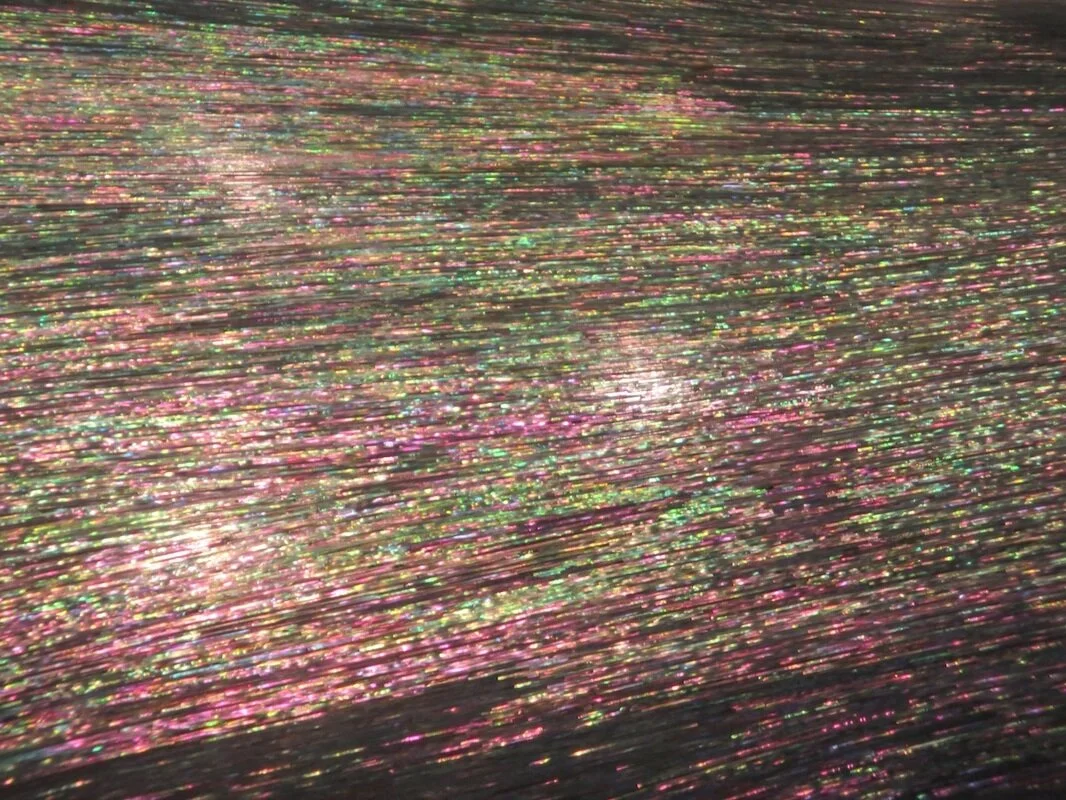

Detail of "1880-Summer-Forest-Gogh Series" (2007), by Kim Yousun. On loan from the National Museum

of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

Over the years, the luminosity and beauty of abalone shells have made them much more than simply a material to work with. For Kim Yousun, mother-of-pearl evolved into a symbol of hope, one which she shares in an art-therapy series "Rainbow Project" to help people living in orphanages, nursing homes, and prisons to heal emotional wounds through art-making. She says,

The shock I received when I first discovered wet, luminous mother-of-pearl in a narrow, shabby alley in Wangsimri [a district in Seoul] in 1992, and its beautiful lights and hues of a rainbow--that experience marked a turning point in my whole life.....A small abalone shell deep under the sea suffers from coarse stones that keep flowing in, but it creates a pearl out of them, with patience and sacrifice. This...has had a significant influence on me in creating art. Even a small, living creature manages to do something dramatic....So, mother-of-pearl has eventually become my life teacher.

"Pebbles" (2015), by Korean artist Hwang Samyong. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

In front of the mother-of-pearl wall, reflected in a mirrored base, sit three "pebbles." They, too, were created from abalone shells, using a traditional slicing technique employed in many of the Joseon-dynasty (1392-1910) pieces on display in the adjacent Tateuchi Gallery. I watched the painstaking process on a video. Born in 1960, Korean artist Hwang Samyong meticulously applied mother-of-pearl strips as thin as the width of a dime to the smooth, curving surfaces of the fiberglass base.

Detail of "Pebbles" by Korean artist Hwang Samyong. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

The next image is from the video I saw on the thin-slicing technique. To view the video, which reveals the artist's spirit behind his work, just click this link: www.asianart.org/regular/pebbles-by-hwang-samyong/. Hwang Samyong says, "Although it may be an insignificant pebble that can be seen anywhere, through my work and passion, it becomes a work of art."

In the case of both Kim Yousun and Hwang Samyong, as well as a third Korean artist, Lee Leenam, whose work is a fascinating 7.5-minute two-channel video, the results are quite different from the traditional pieces I viewed in the lacquerware gallery. Yet, the past and present coexist not only side by side, but also within the integrity of the original works by contemporary artists.

Across from the contemporary mother-of-pearl artworks is a display of bojagi, a general term for wrapping cloths made in Korea for different functions and people. According to Youngmin Lee, a Korean bojagi artist and teacher in the Bay Area, "Jogak-bo, the art of Korean patchwork wrapping cloths (bojagi), embodies the philosophy of recycling, as the cloths are made from remnants of leftover fabric. It also carries wishes for the well-being and happiness of its recipients. During the rigidly Confucian society of the Joseon dynasty, it was one of the few creative outlets available to women."

Traditional bojagi, 1950-1960. Silk. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Traditional bojagi from studio of Hang Sang-soo. Silk. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Long considered a women's domestic craft, in the 21st century fiber artists have rediscovered bojagi for its aesthetic value. Internationally, they are creating their own interpretations, using traditional techniques and a wide variety of materials. Every other year, there is a Bojagi Forum in South Korea that highlights the old and the new, the traditional and the modern, displaying exquisite artwork. The next one is coming up soon, September 1-4, and I am sorry to miss it.

Youngmin Lee is skillful not only in traditional bojagi, but also in adapting it for a contemporary look. In the following first piece, she painted and layered silk organza while using traditional techniques to stitch together the layers and embellish the top. In the second piece, based on viewing mother-of-pearl black lacquerware, again she used a traditional technique to create an original image. Youngmin explains that she specifically chose the "jewel pattern" to help her reproduce the feeling and process of Korean lacquerware onto fabric. She made the piece as "an homage to the enormous labor and care that...artisans endured to prepare and inlay the natural materials on wooden surfaces." Although she used fabrics instead, she still sought to achieve the same effect of luminosity.

Contemporary bojagi (2016) by Youngmin Lee. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Detail of bojagi by Youngmin Lee. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Contemporary bojagi by Youngmin Lee. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Detail of contemporary bojagi by Youngmin Lee. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Artists continue to reinterpret the designs, textures, and techniques of traditional crafts or folk art into new forms. Each artist applies his or her individual perspective in a departure from tradition, while still honoring it. That this is happening around the world, not just in Korea, reflects a desire for reinvention and originality without discarding cultural heritage. As artists mine the past for contemporary artwork, it's hard not to think that what we might have considered passé actually has timeless appeal as well as ongoing vitality and relevance.

Questions and Comments:

What traditional crafts or folk art come to mind as inspiration for new artwork?

Which artists do you consider particularly successful in translating tradition into contemporary art?

How are you mining the past in your own artwork?

*Note: To view the conversation that was started on the former Weebly site of this blog and add your comment, click here or to start a new conversation, click "Comment" below.