Appreciate the Art but Despise the Artist?

Two Sundays back, a friend and I went to see Degas: A Passion for Perfection at our community theatre. Because I’d already found several films from Exhibition on Screen to be illuminating about the artists and their art, I looked forward to this one as well.

Source: exhibitiononscreen.com/films

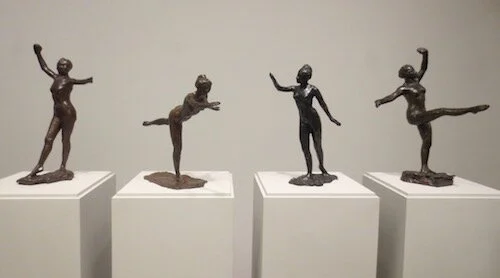

I certainly learned interesting tidbits about the Parisian Edgar Degas (1834-1917): the loss of his mother, a Creole from New Orleans, Louisiana, when he was only 11 years old; his law education forsaken for art; his greater interest in process over product, so he never signed anything until it was sold; his ability to work in different mediums; his failing eyesight leading him away from painting, drawing, and printing to wax sculpture; his never marrying or having an intimate companion; his preference for a studio when his compatriots worked en plein air. But what I had never read about before and heard in this film is that he was called a misogynist, misanthrope, and an anti-Semite. This information gave me pause. It also led me to reflect on a complex conundrum.

“In a café” or “L’Absinthe” (1873), by Edgar Degas. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

What happens when we find out that our favorite painter, poet, sculptor, novelist, musician, actor, dancer, or singer has been outed as a racist, rapist, homophobe, child molester, or murderer? How do we respond? How do we deal with what we consider offensive attitudes and reprehensible behavior? Do we keep supporting the person’s creative output? Do we stop loving that artist’s work? Do we simply consider it a case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde? After all, isn’t everyone capable of both great generosity and compassion and awful thoughts and deeds? I wrote a book about a meditation master who embodied sterling spiritual qualities, but that doesn’t mean he was perfect. People have commented on the serenity in some of my textile art, but that doesn’t mean I’m always peaceful. I’m not. Aren’t most of us a mass of contradictions?

“Self-Portrait” (ca 1857), by Edgar Degas. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

All these questions popped up as we left the theatre and pondered what American literary critic and writer Lionel Trilling (1905-1975) called “the bloody crossroads” where art and morality intersect. Like anyone else, an artist can be influenced by the cultural, social, and political climate of his/her times. Do we hold artists accountable for what may have been considered acceptable then, such as patriarchy and racism?

“Tired Dancer” (1882), by Edgar Degas. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

As an example, during the Dreyfus affair (1894-1906), Degas doggedly maintained his condemnation of Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935), a Jewish artillery captain in the French army who was falsely convicted of passing military secrets to the Germans. Degas did so even after it was clearly recognized that the affair was a miscarriage of justice and anti-Semitism. Dreyfus was exonerated and pardoned following almost five years of imprisonment on Devil’s Island in French Guiana. At the same time, other artists and writers in France came strongly to Dreyfus’s defense: novelist and playwright Émile Zola (1840-1902), stage actress Sarah Bernhardt (d.1923), and Nobel Prize-winner in literature Anatole France (1844-1924), among others, including scientists and politicians. Then why did Degas persist in his ignoble conduct?

“The Orchestra at the Opera” (ca 1870), by Edgar Degas. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

I know that I won’t be able to look at Degas’s art anymore without remembering what I learned about him. Still, I can’t denigrate the work itself. I’ve come across too many nasty things about too many well known artists and writers. (I recently read that Virginia Woolf dressed in blackface at a party and was famously cruel.) Maybe that means we expect too much of them. Yet, when someone mentions a scandal involving a politician, I don’t flinch. Instead, I notice jaded thoughts pass through my mind, such as: “Oh, par for the course.” On the other hand, we apparently expect stellar artwork to reflect stellar individuals.

“Interior” (1868 or 1869), by Edgar Degas. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

In response to the question, “Can you hate the artist but love the art?” NY Times ethics columnist Randy Cohen comments: “It’s hard to be a good person; it’s hard to produce great work. Most of us accomplish neither. To demand both might be asking more than human beings are capable of. To deprive oneself of great work created by a less-than-great person seems overly fastidious.” The artwork itself is blameless, even if the person who created it is blameworthy. That holds, unless the artwork is also intended to vilify women, ethnic groups, people of color, and so on, or to incite violence against them.

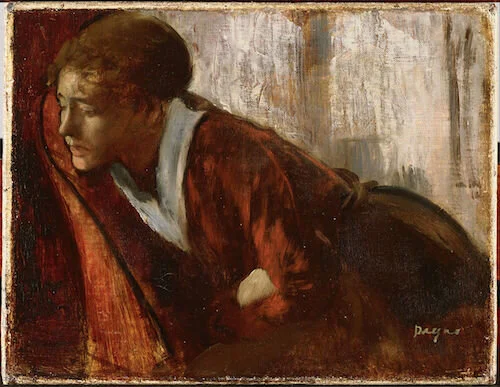

“Melancholy” (late 1860s), by Edgar Degas. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

The dilemma is that great art can be created by rotten people and good people can create not-such-great art. There are also wonderful artists, writers, musicians, composers, and dancers who hone their craft diligently all their lives without ever being recognized. Did anyone say life is fair?

“L'Étoile” or “Danseuse sur scène” (ca 1876), by Edgar Degas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

What to do? When I find that a company whose products I had regularly purchased are financially aiding groups whose motives and actions are in direct opposition to my ethics, I stop buying anything from them. I also prefer not to provide any support that would enable the artist to continue what is inimical to me, but that doesn’t mean I have to condemn the art that I’ve enjoyed.

“The Convalescent” (ca 1872-1887), by Edgar Degas. The Getty Center, Los Angeles. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Writing for The Washington Post, Tim Page reflected on this issue on November 11, 1995. He pointed out that buying CDs by Cat Stevens meant the money would go to Yusuf Islam, the name the singer took on as a Muslim fundamentalist since the 1970s. As such, he publicly endorsed Ayatollah Khomeini's fatwa handed down to Salman Rushdie after the 1989 publication of The Satanic Verses. According to Page, the former Cat Stevens donated most of his publishing rights and much of his fortune to various religious organizations, some of which supported the Rushdie death sentence. Page didn’t throw out the recordings he already had but decided that he would not purchase any more. In the end, of course, it comes down to a personal choice, to what feels right for each of us.

Modeled (ca 1880s), by Edgar Degas. Cast in bronze (1919-21). Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

When I think of great art coming out of not great people, I recall the paradox of a pure white lotus emerging from the muddy and murky conditions of a pond. Do we consider the flower any less beautiful?

White lotus. Photo by Giriraj Navhal. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

Questions & Comments:

How do you feel when you learn that an artist or writer whose work you appreciated turned out to be a miscreant?

When you suddenly know dismaying facts about an artist or writer, do you look at the work differently thereafter?