Partners in a Life of Art

From the outside, I’ve long viewed marriages between creative individuals as something enviable. There’s someone with whom to discuss ideas, techniques, and process; someone who can provide feedback and give a nudge when either of you feels stuck. And, not least, you can commiserate over setbacks and celebrate successes. Like other idealistic notions I’ve held, this one too has come under scrutiny. The many biographies and autobiographies of artists I have read over the years have certainly tarnished the romanticized image I held. Rather than only a haven of mutual support, I learned of competitiveness and jealousies, even betrayals. Given human nature, maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised. However, I’m glad to say that my disillusionment does not apply to certain creative partnerships I do admire, including my friends who are artist couples.

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo (unknown date). Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Still, I am aware that artistic marital bliss is not necessarily the norm. There are famous painful relationships. Take the Mexican painters Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and Frida Kahlo (1907-1954). Their tumultuous marriage flashed on and off, on and off.

Frida and Diego Rivera (1931), by Frida Kahlo. Source: fridakahlo.org

It wasn’t enough that Kahlo endured extreme physical discomfort caused by a serious bus accident in 1925. It left her with many broken bones (spinal column, collarbone, ribs, pelvis), 11 fractures in her right leg, a dislocated and crushed right foot, and a dislocated shoulder. She also suffered the anguish and sorrow of infidelities by Rivera, who was twice her age. In turn, she cheated on him. Yet this didn’t seem to break their love for one another. In fact, their attachment led to abundant creative expression as well as to activism and advocacy for Indigenous peoples of Mexico.

“From the Conquest to 1930,” History of Mexico murals (1929–30), fresco by Diego Rivera. Palacio Nacional, Mexico City. Source: khanacademy.org/

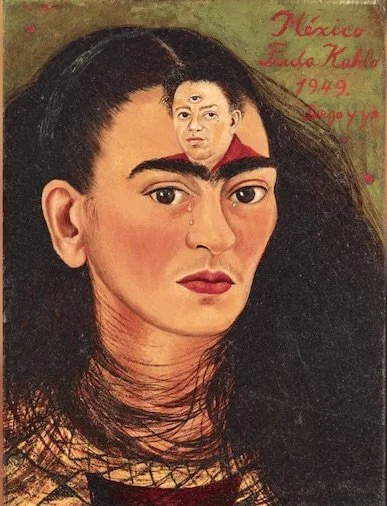

Recently, one of Kahlo’s paintings in which Rivera is included (Diego y yo) sold at Sotheby's auction house in New York for a record $34.9 million, outdoing one of his, which sold for $9.76 million in 2018.

Diego y yo (1949), self-portrait by Frida Kahlo. Photo credit: Sotheby’s. Source: cnn.com/

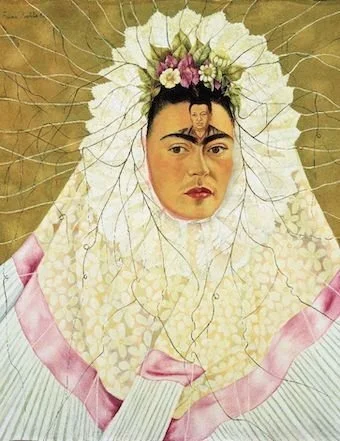

Six years earlier, Kahlo had also created this self-portrait with Rivera “on her mind.” She painted it in 1940, when they divorced, but didn’t complete it until 1943. She is wearing a headdress from Tehuantepec, in the state of Oaxaca.

Diego on My Mind (Self-Portrait as a Tehuana) (1943), by Frida Kahlo. The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art, The Vergel Foundation, Conaculta/INBA, © 2018 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Source: learn.ncartmuseum.org/

While Rivera and Kahlo lived out the high drama of their relationship, other couples have managed to come across as lovingly cooperative. Joseph (1888–1976) and Anni (1899-1994) Albers come to mind. These lifelong artistic adventurers and modernism pioneers were from such different backgrounds that their marriage seemed improbable. He was an elementary schoolteacher from an industrial area in northwestern Germany and she was from an affluent Jewish family in cosmopolitan Berlin. They met in Weimar, Germany in 1922 at the Bauhaus, a school that integrated crafts and the fine arts. They wedded in 1925.

Josef and Anni Albers. Source: albersfoundation.org/artists/biographies/

As a female at the Bauhaus, Anni was directed away from the fine arts (engaged in by men) and toward the weaving workshop. Little did anyone realize to what heights she would advance a so-called domestic craft. As she later said, “Any craft is potentially art.” Josef became one of the school’s best-known artists and instructors. Rather than comply with Nazi rules and regulations, he and others decided to shut down the school in 1933. As outsiders at this point, Josef and Anni had to leave. They wound up immigrating to America and joining the newly commissioned Black Mountain College in North Carolina. While they never had their own children, they became artistic “parents” to Ruth Asawa, Ray Johnson, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, and Susan Weil, among many others. The list is too long to include here.

Josef Albers’ color model features three Primary colors: red, yellow and blue; Secondary colors: orange, purple and green; and Tertiary colors created via admixture of Secondary colors, as per 'Interaction of Color' (1963). Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

The Alberses left Black Mountain College in 1949, and Josef became chairman of the Department of Design at the Yale University School of Art (1950-58). Both he and Anni continued to concurrently but independently explore new paths in their own work: he, in colors, printmaking, collages, and abstract painting; she, in weaving, screenprinting, and essays about design. As guest instructor at art schools in Europe as well as North and South America, Josef trained a whole new generation of art teachers.

Paintings by Josef Albers at the Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco: top row, left to right, Homage to the Square (1969), Study for Homage to the Square (1972); bottom row, left to right, Homage to the Square (1957), Homage to the Square: Confident (1954); far right, Homage to the Square: Starting (1968).

Not swayed by the art world’s latest trends and changing fashions, during 50 years of marriage, the couple respectfully fostered each other’s creativity without collaborating. And, according to the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, they shared a deeply held “conviction that art was central to human existence and that morality and creativity were aligned.”

Six Prayers (1966-67), a “pictorial weaving” by Anni Albers. Tate Modern, London. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

I wish I could have gone to the Anni Albers show (October 2018-January 2019) at the Tate Modern in London. Above is one of her works from that show. It was commissioned by the Jewish Museum in New York to memorialize the six million Jews who died in the Holocaust. But I did get to see smaller pieces inspired by the landscape and architecture of Mexico, which she and Josef visited frequently from 1935 into the late ‘60s. When I was in Chicago to give a presentation and teach a workshop a couple of years ago, I took the opportunity to visit the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC). There, I viewed an exhibition of six women artists who were transformed by their time south of the border: “In a Cloud, in a Wall, in a Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico at Midcentury.” One of them was Anni Albers. (The others were Clara Porset, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Ruth Asawa, Cynthia Sargent, and Sheila Hicks.)

Left to right: Red and Blue Layers (1954), cotton, and Red Meander (1954), linen and cotton, by Anni Albers. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and Private Collection. The Art Institute of Chicago.

Visits to Mexico led to a change in palette, from muted hues to radiant colors. Her overall oeuvre demonstrates that she was able to combine traditional craft and modern art in her investigation of geometric abstraction. She became aware, in her travels, that her fascination had distinct echoes from ancient Indigenous weaving. The sophisticated geometries she found were like the patterns she explored in her own studies. She had come face to face with this abstract visual language that had been around for millennia.

Detail of Red and Blue Layers (1954), by Anni Albers.

Detail of Red Meander (1954), by Anni Albers.

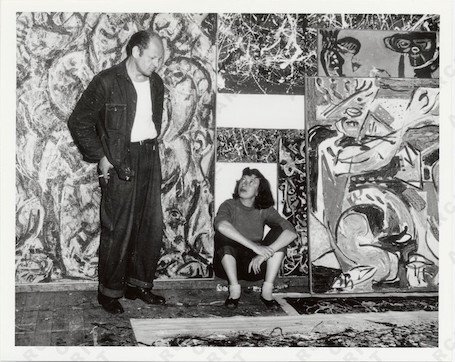

Love stories between artists—of various disciplines and styles, of diverse ethnicities and sexual orientations—abound. There was one between Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst, another between Man Ray and dancer Juliet Browner. The one between Willem de Kooning and Elaine Fried de Kooning was often disrupted by alcoholism and extramarital affairs. They separated for about two decades and then reunited. There was the stormy partnership between Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, their strident arguments and his over-the-top drinking legendary. Some say they served each other alternately as lover, muse, critic, companion, and alter ego. Many of Merce Cunningham's most famous innovations in dance and choreography were developed in collaboration with his life partner, composer John Cage.

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in front of his work, c. 1950.

Photo: Archives of American Art. Source: khanacademy.org/

And, of course, there was the great romance between Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe, though it did not necessarily sail on an even keel. She moved away from the sophistication of New York for the stark beauty, quiet, and solitude of New Mexico. While he had been her top promoter, it was off in the high desert that she evolved artistically on her own.

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns (1950s). Photo credit: ?. Source: theartgorgeous.com/

Robert Rauschenberg married Susan Weil, but within three years they were divorced and, thereafter, his love affairs were with Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns. The relationship with Johns is considered one of intense emotional involvement and creative achievement. Together, they explored alternatives to Abstract Expressionist picturemaking. Rauschenberg once remarked of this period: “We gave each other permission…” and “each of us was the most important person in the other's life.” His final partner, for 25 years, was visual artist Darryl Pottorf. So much creativity burst forth from so many love relationships among artists.

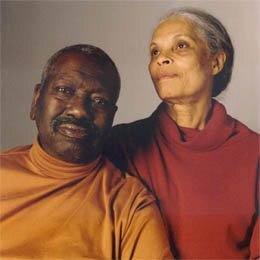

Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight. Photo by Spike Mafford, Courtesy Francine Seders Gallery, Ltd.

Source: historylink.org

Then there’s the enduring (50 years) marriage of Jacob Armstead Lawrence (1917-2000) and Gwendolyn Clarine Knight (1913-2005), painters and printmakers, art educators and activists. They were both students of the sculptor Augusta Savage (1892-1962). Lawrence, born in New Jersey, and Knight, from Barbados, met in 1934, during the Harlem Renaissance, while employed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). They married in 1941.

Lullaby (1992), by Gwendolyn Knight. Offset lithograph on paper.

Collection of Connie Bostic. Source: blackmountaincollege.org/

Theirs was a collaborative partnership, providing constant support as well as critical guidance, inspiration, and stimulation for each other. As Lawrence once noted: In our life together, we share our opinions but reserve them until one or the other of us is ready to discuss the work. Once we’ve commented on each other’s work, we are free to choose whether or not we make changes based on those comments. There really is no pressure. Sometimes you wouldn’t even understand a remark until years later. To me, that sounds like respectful appreciation and consideration.

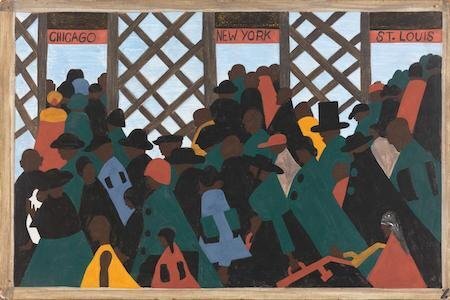

The Migration Series, Panel no. 1: During World War I there was a great migration north by southern African Americans (1940-41), by Jacob Lawrence. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Source: phillipscollection.org/

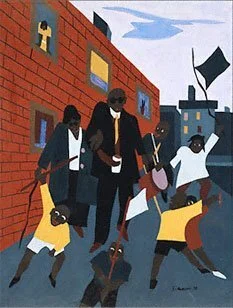

I also find their integrity and authenticity meaningful. Like the Alberses (whom they met at Black Mountain College when Josef Albers invited Lawrence to teach a summer session), they did not follow artistic vogues. While the rest of New York was deeply ensconced in the Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s and ‘60s, Lawrence and Knight preferred a figurative style to depict the human experience. Many of his works from the 1930s and ‘40s recorded everyday life in Harlem: people on their stoops, street orators, pool halls, and funerals. Attracted to the historical narrative of African Americans, he painted the stories of Toussaint L’Ouverature (leader of a slave revolt in Haiti), John Brown, Harriet Tubman, and the Great Migration from the Southern to the Northern states. Later, he included the Civil Rights Movement, aviation, builders and their tools (he loved tools). In 1970, Lawrence said: If at times my artworks do not express the conventionally beautiful, there is always an effort to express the universal beauty of man's continuous struggle to lift his social position and to add dimension to his spiritual being.

New Orleans (1941), by Gwendolyn Knight. The Johnson Collection, Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Source: thejohnsoncollection.org/

Gwendolyn Knight was enamored of both the animal and the human form. She and Lawrence heartened one another artistically though their pursuits were independent. Her subject matter was more intimate and her method more spontaneous. Knight painted portraits of friends, poetic studies of dancers and creatures, landscapes, and still lifes. She worked in oil, watercolor, and gouache. Though she did not get the same recognition as Lawrence, she said, in 1988, that it “wasn’t necessary for me to have acclaim. I just knew [since childhood] that I wanted to do it [paint], so I did it whenever I could.” Her first retrospective did not come until 2003, when she was nearly 90 years old, at the Tacoma Art Museum.

Beggar No. 1 [Aka "Blind Beggars"] (1938), by Jacob Lawrence. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of New York City W.P.A., 1943. Source: whitney.org/

Knight and Lawrence had some wonderful adventures together, including moving to Nigeria before he was offered a tenured professorship at the University of Washington. They lived in Seattle until they died, five years apart. Again, like the Alberses, they had no children, but left a lasting legacy through their artistic contributions, teaching, and a foundation that established charitable gifts to help artists and programs for children as well as the research and study of American art.

I’ll close with something Lawrence said to Josef Albers in 1946: My belief is that it is most important for an artist to develop an approach and philosophy about life. If he has developed this philosophy, he does not put paint on canvas, he puts himself on canvas.

Questions & Comments:

If you are part of an artistic partnership, how does it enhance your creativity? What are the advantages? Any disadvantages?

What have you learned about artistic couples, famous or not? Were/are they successful in both love and art?