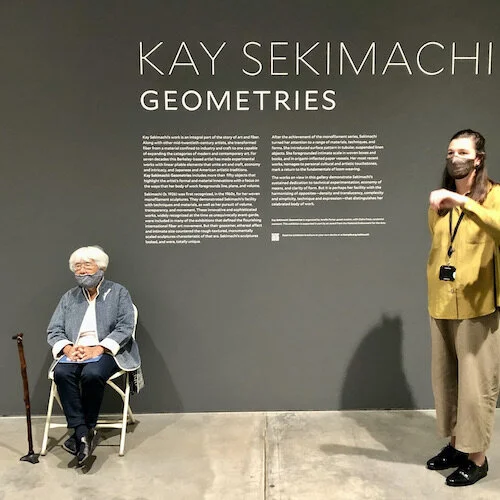

Kay Sekimachi: Geometries

Kay Sekimachi at her loom. Photo credit: Kelly Sullivan.

Source: berkeleyside.org/2021/05/23/

Although nearing 95, Kay Sekimachi is still happily weaving. A petite, white-haired woman with a ready smile and a twinkle in her eyes, she is a rock star in the fiber art world. Considered the “weaver’s weaver,” she has influenced innumerable fiber artists and craftpersons and has had her work displayed internationally and collected by museums. Which is why we had a Textile Arts Council (TAC) event on July 30 to view an exhibit curated by Jenelle Porter. More than 50 objects highlight Kay’s innovative and precise use of materials and techniques over seven decades. The extra special feature was her willingness to join us. As we walked through “Geometries” at the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) and sipped tea and coffee afterward in the museum’s Babette Cafe, Kay indulged our questions. In this time of COVID, we were grateful that the museum opened early for us so that we could have the gallery to ourselves. [Many thanks to Sherry Goodman, Director of Education and Academic Relations, for her kind assistance.]

Kay first focused on textiles as a child. When she was about ten, she started constructing thousands of outfits for her paper dolls, “while we wore rags,” she remarks with a laugh. She still has that “couture” collection. Then, from 1946 to 1949, while studying painting, silk-screening and design at the California College of the Arts and Crafts in Oakland, she wandered into the school’s weaving room. Thoroughly enchanted, she decided to spend her last $150 on a loom. She has never regretted that impulse.

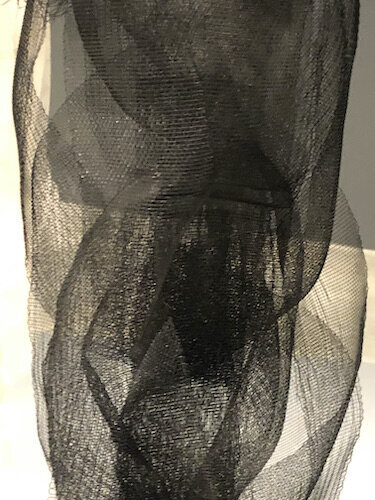

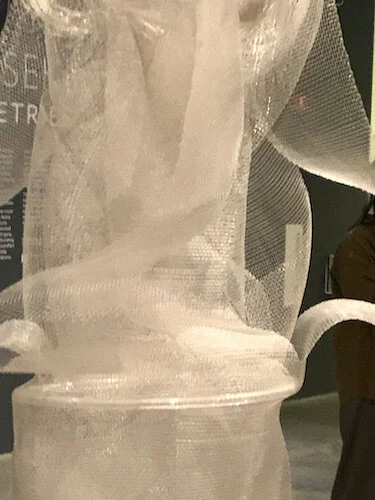

Initially, her weaving resulted in utilitarian items—placemats, hand towels, etc. But, in 1954 and 1955, she learned a different approach from Trude Guermonprez (1910-1976). A Bauhaus-influenced weaver and teacher who emphasized free experimentation on the loom, she taught Kay double weaving and inspired her to transform her work. Soon enough, Kay was creating small abstract tapestries and eventually wall hangings. Then, in the 1960s, the invention of nylon monofilament led her on another exploration. As far as she knew, no one else had woven with it. A gift from a friend whose mother worked for the manufacturer enabled her to weave interlocking layers on the loom. Once she removed them from the loom, Kay shaped them into volumetric, translucent forms.

monofilament weavings by Kay Sekimachi

detail of monofilament weaving by Kay Sekimachi

However, such weaving was neither simple nor easy. Because monofilament is slippery, the process was slow and laborious: it took her an hour of weaving to produce one inch. The “white” clear monofilament was standard. In order to make it black, she used ordinary Rit dye.

monofilament weaving by Kay Sekimachi

detail of monofilament weaving by Kay Sekimachi

Kay is an artist who keeps trying something new. As she has said, “I just love the motion of weaving. There’s so much you can do—double weaving can lead to triple weaving; triple weaving can lead to quadruple weaving. I have a lot of expertise and still a lot to learn.”

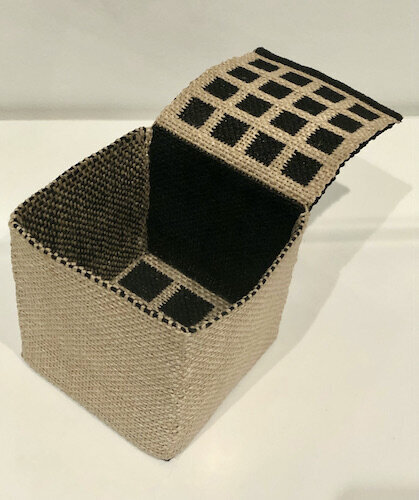

In 1974, she was asked to participate in the 1st International Exhibition of Miniature Textiles in London. The invitation prompted her to weave a series of small-scale nesting boxes. The simplicity of their shape and colors belies a complex construction. Using coarse linen, Kay molded a two-dimensional piece into a seamless, rectilinear box. She has gone on to create a variety of containers using this method but with fine gauge linen and ikat patterning.

woven linen box by Kay Sekimachi

woven linen box by Kay Sekimachi

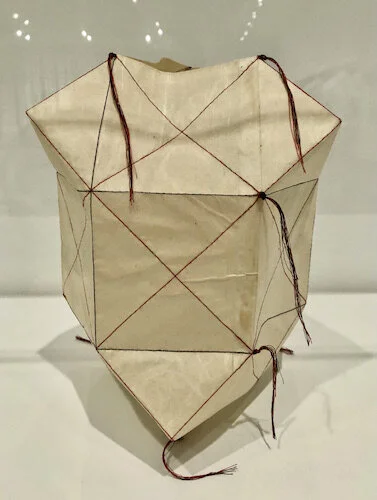

While making preliminary maquettes for her boxes with paper, Kay recognized the medium’s potential. She ended up forming a series of small-scale sculptures by folding and machine stitching antique and vintage Japanese paper. She worked with kiri wood paper (paulownia tree) as well.

paper box by Kay Sekimachi

paper box by Kay Sekimachi

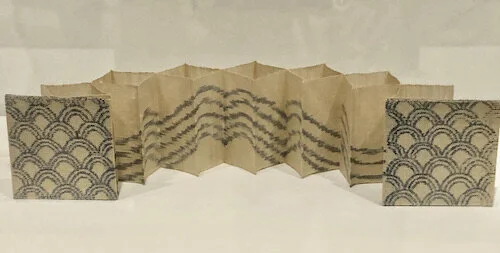

For two decades, beginning in 1980, Kay also wove linen accordion-fold books. They can be held in one’s hands, to be “read” like a book. Her inspiration was a miniature book of woodblock prints by ukiyo-e master Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). She treasured this book while living with her family in Japanese internment camps (Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, and Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah) from 1942 to 1944.

woven linen book by Kay Sekimachi

woven linen book by Kay Sekimachi

As someone who is drawn to an aesthetic of elegant simplicity, I enjoy a sense of serenity in Kay’s work. She even pays homage to another artist whose paintings similarly convey a calm presence: Agnes Martin (1912-2004). On one wall hangs a framed series of small weavings that are reminiscent of them.

close-up of a weaving paying homage to Agnes Martin,

by Kay Sekimachi

The images here are just a sampling of what’s on view in Geometries. I am in awe of Kay’s dedication to experimentation as well as her ability to successfully marry craft with art, simplicity with complexity, density with translucency, Japanese traditions with American expressions. That she is still working, now weaving long obi-like and scroll-like pieces, is inspiring for all of us hoping to keep our creative spirit alive at any age.

weaving by Kay Sekimachi, inspired by vintage Japanese silk obis and scrolls

close-up of weaving by Kay Sekimachi

If you can get to Berkeley, the exhibit runs until October 24.

Questions & Comments:

What artists do you know who are still creating well into their later years?

What keeps their creative juices flowing?

What adaptations have they had to make?

How about you: still coming up with new ideas and learning new techniques?