On the Move: Art About Migrating

Since the emergence of what are called the first archaic human beings out of Africa some two million years ago, the migration of individuals and families has been constant. Whatever the reasons—politics, economics, war, health, famine, environment, ethnicity, or religion—people leave what is familiar and seek new lives in unfamiliar places that are full of uncertainty and often lack a welcome. Similarly, ecological disasters and destruction of habitat force animals, birds, and marine creatures to seek shelter and food elsewhere.

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal (2015). Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate. Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online, 11.

http://doi.org/10.4137/EBO.S33489 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4844272/ Source: en.wikipedia.org/

Because this is an important universal topic and a crucial current issue—100 million individuals have been forcibly displaced worldwide—I decided to propose an exhibit to reflect diverse interpretations of both human and nonhuman movement. On the Move: Migration/Emigration/Immigration opened at the Gualala Arts Center in Northern California on October 7 and will end November 20.

On the Move: Migration/Emigration/Immigration, an exhibit in the Burnett Gallery, Gualala Arts Center (GAC).

Photo courtesy of GAC.

Fellow artist Paula J. Haymond graciously agreed to be my co-curator. She invited local artists on the Mendocino/Sonoma coast and I invited artists from other parts of California and far beyond. Since we could not occupy the entire art center, we focused on being as diverse as possible within one gallery. Our artists represent a wide range of cultural backgrounds: African, Basque, Brazilian, Ecuadorian, Japanese/Chilean, Korean, Mexican, Swedish, Ukrainian, and other Europeans. They also work in a variety of media, using wood, paint, paper, clay, threads, metal, photos, and more to create prints, books, stitched maps, collages, scrolls, paintings, handwoven textiles, and installations.

Before we make the entire exhibit available online, here are a few works and statements about them to convey a sense of what we included.

Detail of Color Border, by Carolina Barreira.

Photo courtesy of the San Francisco School of Needlework and Design.

The above detail is from a densely embroidered world map by Brazilian fiber artist Carolina Barreira. Borders are both metaphorical and literal––some are fixed while others have fluidity and movement. Externally, borders are both visual and physical structures that serve to define lands, politics, cultures and linguistic variations. Barreira prefers a world without borders, a world with colors and love instead. She spent eight hours a day for 45 days to complete the entire map.

Tira y Afloja (Tug of War), by Sandra C. Fernández.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ecuadorian printmaker Sandra Fernández finds that being an immigrant is like a tug of war, in which two sides are set against each other in a test of strength. “When you uproot to a new place, you are constantly negotiating between your past and your future,” she says. “The dominant culture wants to assimilate you, while your heart knows that you already had a culture that made you who you are.”

Steamship Ticket, by Susan Zimmerman.

Photo by Sibila Savage.

There is an interesting story behind San Francisco Bay Area fiber artist Susan Zimmerman’s piece, Steamship Ticket. While she uses historically accurate steamship tickets circa early 1900s, she created it to honor the memory of her grandmother who, at age 17, stole a steerage-class steamship ticket off the kitchen table so she could run off to America and leave Eastern Europe behind. Zimmerman dedicates this work to all immigrants who made that long ocean journey to America and to all immigrants today who wish to make America their home. She printed public domain steamship tickets on vellum, crumpled and tea-aged them, sewed them together by hand, and embellished with ink and charcoal drawings of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, along with aged canvas and grommet reinforcements.

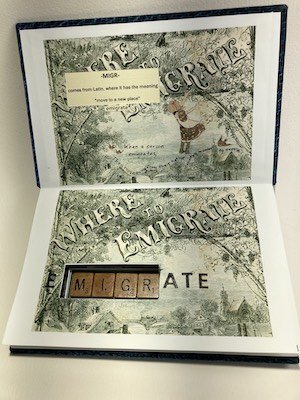

Migrate, by Polly Frenaye-Hutcheson.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Polly Frenaye-Hutcheson, who lives on the Mendocino coast, creates engaging and evocative books. Migrate is a play on the etymology of migr-, derived from the Latin, “move, shift.” As you flip a page, the root becomes migrant, immigration, and so on, along with different images.

Bracero Flag, by Consuelo Jiménez Underwood.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Consuelo Jiménez Underwood, whose work can be seen at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., divides her time between the Mendocino coast and the San Jose area, where she was a university professor for many years. Bracero Flag is one example from a flag series. Woven, silk screened, and embroidered, using silk, linen, and rayon, it reflects on the history of indigenous people being imported from Mexico during World War II to work as agricultural laborers in the U.S. Yet, after the war, they were deported back to Mexico rather than be allowed to become citizens. As Underwood states, “The deportees were nameless, faceless, but left behind real relationships with other ‘Americans’.” Her piece demonstrates the merging of the U.S./Mexico border, just as the nations’ economy and culture are merged.

Objectified Other, by Dave Young Kim.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Grateful to Korean artists who immigrated to the U.S. and pioneered a path for other Koreans to follow, Los Angeles-based artist Dave Young Kim portrays Yong Soon Min. According to Kim, Min was born near Seoul when the Korean War ended in armistice and is now a professor at the University of California, Irvine. Within her own art practice, she examines issues of representation and cultural identities, along with the intersection of history and memory. Objectified Other is Kim’s painted recreation of one of her earlier photo-based works in her “Make Me All” series.

Native Lands, by Ken Kalman. Photo courtesy of the artist.

I wanted some of the pieces in the exhibit to be interactive, that is, touchable. Polly Frenaye-Hutcheson’s books and Ken Kalman’s constructions fit the bill. A San Francisco Bay Area artist, Kalman made a map table of the United States. Each state is a cutout, just like jigsaw puzzles. Only here, when you pick up a state by a knob, a portion of another map underneath becomes visible, one which reveals the tribal nations that, in too many instances, were displaced by white settlers. It’s a powerful visual of an ugly history. Kalman made the map table with an aluminum sheet, cast aluminum, rivets, screws, and paper.

Although not visible in this photo, I posted a map of the Trail of Tears behind the table. In the 1830s and 1840s, that trail was the deadly journey the Cherokee Nation had to make on foot in a forced migration from their ancestral homes in the Southeast to Oklahoma.

Detail of 23 and Me DNA Data Translations in Color Pigment,

by Cynthia Brannvall. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Cynthia Brannvall, a Berkeley artist and professor of art history, created 23 and Me DNA Data Translations in Color Pigment. Her DNA results cover a very long scroll of rice paper and disclose how much migration is in her background: European: 59.01%—Finnish: 24.7%, Scandinavian 15.2%, British & Irish 1.5%, Iberian 1.2%, Broadly Northwestern European 10.1%, Broadly Southern European 3.3%, Broadly European 3.2%, Sub-Saharan African: 38.7%—West African 34.8%, African Hunter-Gatherer 1.7%, East African .2%, Broadly Sub-Saharan African 2.1%, East Asian % Native American: .5%—Native American .3%, Broadly East Asian & Native American .2%.

Hung to the side of the scroll, 14 slip cast molds painted with nail polish look like mask fragments. The result of Brannvall’s DNA diversity is that she finds her multiracial identity “has meant navigating expectations, assumptions, and biases that can be hard to pin down. A double take, crazy-making form of racism comprised of a million subtle gestures, projections, double standards, and the burden of proving my exception….Never white or black enough to be given the benefit of the doubt. No matter what someone assumes about how I look (or how anyone looks), there are all kinds of migration/immigration patterns in the background, as testified by my DNA readout.”

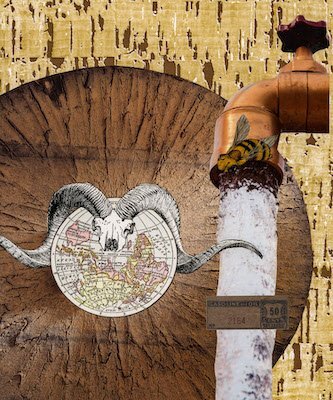

No Water, No Life, by Sharon Nickodem.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Collage artist Sharon Nickodem, another resident of the Mendocino coast, approaches the exhibit’s theme from a different angle. She examines how environmental factors can affect the migration/immigration of humans, animals, and other species in a significant way: effects of constant warming, increase in extreme weather, and rising sea levels. Through her research, Nickodem discovered that water deficits, rather than water excesses, are linked to 10 percent of the rise in global migration.

Since there are 19 artists in On the Move, many with multiple works, this post can give but a taste of how diverse the show is. As well as the pieces referencing human migration, there are photographs and paintings of birds and fish as well as collages about all manner of creatures. If you have a chance to stop by Gualala Arts Center (last day is November 20), I hope you’ll find the exhibit as rewarding as Paula and I enjoyed curating it. We invite viewers to consider where their own ancestors have come from (and to pin that place on a large map in the gallery entrance) and to extend compassion to refugees who also desire a better life for their children.

Questions & Comments:

If you’re an artist, have you ever created a piece about migration/immigration? If so, please describe it.

If you’re familiar with artwork by immigrants or about immigration, which are you most drawn to?

How can art dealing with crucial issues make a difference, and even effect change?