Inspiration: Your Ancestor Was an Artist

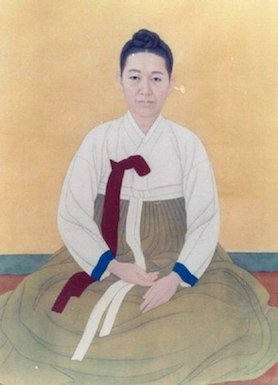

Shin Saimdang (신사임당, 1504 – 1551). Korean painter, calligraphist, and poet. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

I think it was during my first, maybe second, trip to Korea that I became acquainted with the work of Shin Saimdang (1504-1551), an artist I had never heard of. While visiting one of Seoul’s many interesting museums, I happened on an exhibit of her paintings. I might have found the experience unremarkable except that she created a new painting genre of plants and insects, known as Chochungdo, during the mid-period of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). It was a time when Confucian ideals dictated that, once married, women were not to be public with their gifts and talents. How then did she become so well known? Clearly, there was a story here.

Chochungdo, by Shin Saimdang. Sackler Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

That day in the museum, I couldn’t have known that I would later meet Shin Mihe (family name is followed by given name), a fine arts photographer whose ancient ancestor is Shin Saimdang. And neither of us could have predicted that Mihe would later produce photographs inspired by her long ago relative’s artwork. Synchronicity and serendipity never cease to astound and delight me.

Chochungdo, by Shin Saimdang. Ink and color on paper; part of 8-panel folding screen. National Museum of Korea, Seoul. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Chochungdo, by Shin Saimdang. Ink and color on paper; part of 8-panel folding screen. National Museum of Korea, Seoul. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

There is a refined, even lyrical aesthetic to Shin Saimdang's paintings, in which she favors butterflies, insects, flowers, fruit, vegetables, fish, birds, and other aspects of landscape. What may have appeared too mundane and insignificant—an eggplant or a grasshopper—to most people became worthy of careful observation and rendering. There is a legend that her painted insects appeared so real that chickens would mistakenly peck at them. While approximately 40 paintings of ink and stone-paint colors are known, many others might still exist.

White Herons by a Lotus Pond, by Shin Saimdang.

Ink on silk. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Shin Saimdang’s real name was Shin In-seon, but she used several pen names: Saim, Saimdang, Inimdang, and Imsajae. Through her mother, Lady Yi, she was descended from queens and kings. As a government official, Saimdang’s father, Shin Myeong-hwa, was mostly away, leaving his wife to live with her parents and direct the education of their five daughters. Saimdang’s maternal grandfather taught her as thoroughly as he would have done for a grandson. Having no brothers, she received instruction that would have otherwise been bestowed only on a son. In addition to Neo-Confucianism, history, literature, and poetry, Saimdang was highly skilled in calligraphy, embroidery, and painting as well as writing and drawing. Surprisingly for the customs of that time, her father preferred to marry her to a man who, rather than wealthy or prestigious, would allow her to continue with her artwork. The couple had five boys and three girls, whose education was influenced by the one Saimdang had received.

Chochungdo, by Shin Saimdang. National Museum of Korea, Seoul. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Chochungdo, by Shin Saimdang. National Museum of Korea, Seoul. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

How Mihe came to create a series reminiscent of Saimdang’s paintings seems pure happenstance. It was a case of “out of the mouth of babes.” And the babe was her grandson Kion.

K-STREET STILL LIFES: Sowbread & Butterfly, (2021-2022), by Shin Mihe.

Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Mihe recounts how it began: “It takes more than half an hour for Kion to reach the daycare center [in Seoul], which is five minutes away. A piece of grass on the street, a root of another weed next to it, various flowers, a pumpkin tree (a botanical nomenclature given by Kion that the leaves of a poplar tree look like pumpkin leaves), a pine cone, a black fruit, a red fruit, a pebble, an ant, a dragonfly, ladybug and snail’s eggs…he looks at them with sparkling eyes and says, ‘You’re so pretty!’ And then takes another step, strokes them, admiring, ‘you are so pretty too!’” Arranging and showing the composition was the daily routine of a child who, at that time, was not yet two years old.

K-STREET STILL LIFES: Dahlia & Spider (2021-2022), by Shin Mihe. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

The isolation and restrictions imposed by COVID-19 eventually led Mihe to work on a new series, K-Street Still Lifes. Having witnessed Kion’s curiosity and love of Mother Nature, she decided to take up the study of plants, accumulating knowledge that is “as good as Kion’s.” As she learned the names of the plants, she realized that the flowers in the street that she had been photographing were living creatures, each with its own individuality and deserving of respect. They included even the “unimportant” weeds that were an object of wonder in the eyes of her grandson. The flowers, grasses, trees, and insects on the street that she previously had not noticed now came into sight. Mihe admired them as Kion had.

K-STREET STILL LIFES: Garden Balsam & Butterfly (2021-2022), by Shin Mihe.

Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Simultaneously, she suddenly thought of Shin Saimdang’s Chochungdo and wanted to represent the beauty of ordinary things that her ancestor must have felt so many centuries ago. The photographs became, for her, a way of “transcending time and space in modern times.” She brought the natural items into a virtual space and reconstructed them in a new space. And, instead of the usual seal/stamp of one’s name (dojang), Mihe replaced it with Saekdong, Korean traditional color stripes, in an upper corner. [I am sorry that such details, along with the insects, are harder to see in my downsized photos of the large originals, as evident in the museum shot below.]

K-STREET STILL LIFES, by Shin Mihe, solo exhibit at Whanki Museum, Seoul, 2023. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

In the catalogue for Mihe’s exhibit at the Whanki Museum in Seoul [KIM Whanki (1913-1974) is arguably my favorite Korean artist], Jo Joonggeol, former professor of art history at the University of Toronto, makes some interesting points about the photographs. First, there is a sense of “mysterious serenity”as well as “the shock” of what is not there: “All backgrounds have disappeared, and only a single flower (or a few flowers) occupies the canvas, all noise being excluded.” He understands this as a rejection of the banality he typically encounters in most photographs. Instead, he believes that, because Mihe isolates the object from its usual context, she has eliminated any banality. He likens this effect to that achieved by Andy Warhol in isolating Mao Zedong from the context of political power and Campbell’s soup cans from the context of a supermarket or pantry shelf.

K-STREET STILL LIFES: Garden Zinnia, Butterfly & Frog, (2021-2022), by Shin Mihe.

Photo: courtesy of the artist.

In the photographs, the professor notes, Mihe achieves “the innovative effect of unfamiliarity and novelty of the flower.” What he refers to reminds me of Georgia O’Keeffe’s focus in painting flowers: "…in a way—nobody sees a flower—really—it is so small—we haven’t time—and to see takes time like to have a friend takes time."

K-STREET STILL LIFES: Crape-Myrtle & Mantis (2021-2022), by Shin Mihe.

Photo: courtesy of the artist.

The artistry is not about imitating or literally reproducing so-called objective reality, but subjectively representing one’s particular worldview. Each artist, each photographer, can’t help but experience and respond to the same scene differently, even with exactly the same equipment at the same time. It’s not a matter of what the camera is technically capable of, but of what the artist brings—her perspective—to what is photographed. Mihe’s photographic response is both elegant and sophisticated. And just as the Dutch masters dramatically contrasted light and dark, she achieves a kind of chiaroscuro by situating the flower as though against an inky night sky.

K-STREET STILL LIFES: Hibiscus & Dragonfly (©NIBR), by Shin Mihe (2021-2022).

Photo: courtesy of the artist.

I would have loved to see the exhibit in person, but commitments and personal issues didn’t allow for a trip to Korea this year. I am delighted to at least have the internet and a catalogue for virtual viewing.

K-STREET STILL LIFES: Castor-Oil Plant & Ant (2021-2022), by Shin Mihe.

Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Since times are so different, I don’t know whether I’ll ever see a Korean banknote with Mihe’s image and artwork, but the nation has never forgotten her ancestor.

Portrait of Shin Saimdang and Mookpododo, ink drawing of grapes, on the ₩50,000 banknote, newly introduced in 2009, making her only the second woman to ever appear on a South Korean banknote. There are other paintings on the back. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

For more images of K-STREET STILL LIFES and other series by Shin Mihe, visit her website.

Questions & Comments:

Is there an artist in your family that has inspired/influenced you? How?

If you paint or photograph the natural world, what is your particular approach?

Who is your favorite artist of Nature? What is it about that artist’s worldview that attracts your attention?