What’s That Color?

The Munsell color chart as used by the World Color Survey.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Color is part of our every waking moment. Even while asleep, we are capable of dreaming in color. But exactly what color are we seeing? In the Interaction of Color, German-born American artist, poet, printmaker, and educator Josef Albers (1888–1976) asserts: “In visual perception, a color is almost never seen as it really is—as it physically is. This fact makes color the most relative medium in art.” Because colors interact with one another, the same color can appear as different colors, depending on what is next to it. And there are so many different colors, more than I’d ever imagined.

Josef Albers' Studies for Homage to the Square.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Mirka Knaster.

Jeanne Heifetz’s When Blue Meant Yellow: How Colors Got Their Names offers the following fact: the human eye can distinguish 7,295,000 shades of color. Skeptical about this huge number, I looked for verification. It turns out that, indeed, we can discern anywhere from 100,000, at the very low end, up to 10 million colors and possibly way beyond that. Heifetz, a weaver with a lifetime passion for words and colors, delves into the etymology of colors we use to describe everything from nature's gorgeous array to a painter's palette and the hues of clothing. The brief explanations are variously curious, charming, obvious, culturally specific, or historically relevant.

The Blue Boy (Portrait of Jonathan Buttall) (1770), by Thomas Gainsborough. The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

One, in particular, surprised me: "baby blue." It turns out that the custom of dressing boys and girls in blue and pink respectively is fairly modern. I learned that the famous Blue Boy by British painter Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) actually has a companion called Pink Boy. For hundreds of years, in most Catholic countries in Europe, children wore blue from head to toe because it was associated with the Virgin Mary. But in non-Catholic countries, infants were dressed in white. In 1918, "the generally accepted rule" was pink for boys and blue for girls. The reasoning behind this? Astonishingly, pink was thought of as "a more decided and stronger color" and, therefore, more suitable for a boy. Blue was deemed "more delicate and dainty" and, thus, prettier for a girl. By the end of World War II, however, a reversal took hold that is still with us today. I don’t know why, except that ideas, like fashions, come and go. But equating blue with boys and pink with girls seems to hold fast when it comes to buying baby gifts.

Master Nicholls, known as The Pink Boy (1782), by Thomas Gainsborough. Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire, England. Source: artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-pink-boy-229417

Gladly, this is not true for everyone. When a childhood friend’s first grandchild was born, I asked her son’s wife what fabrics she preferred for a quilt. She wanted neither traditional color and, instead, chose a combination of teal, terracotta, and pale coral. I set them in a background of creamy white.

baby quilt (front), by Mirka Knaster

baby quilt (back), by Mirka Knaster

Another interesting details concerns “gray.” It is derived from the Old English graeg, which is related to words in Old Norse, German, and Swedish for "dawn." So gray probably referred to the pale colors at sunrise. Similarly, the word for gray among the Native American Klamath people of southwestern Oregon also comes from a word for "the morning dawns" (pä'kgtĭ). Thus a particular color can evoke a particular image.

Sunrise on the Nigerian coast. Photo by Otu Nwachinemere.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

“Jade," which we generally envision as a shade of green, can actually be anything from white to black. Oddly, the color of this gemstone originates from Spanish: piedra de la ijada ("stone of the flank"). That's because it was thought to be a remedy for kidney ailments. In China, jade has dozens of picturesque names, including "melon peel," "date skin," "chicken bone," "coarse rice", "sky-after-the-rain," "purple of the veins," and "fish belly."

Jade. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

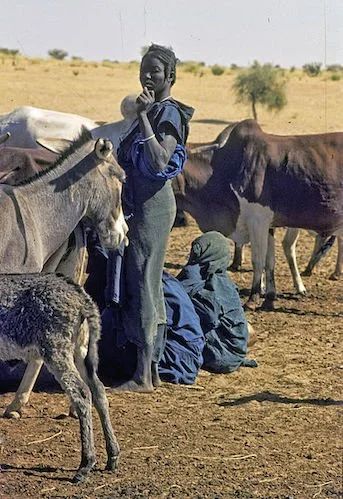

Of all the colors, “indigo” may have the most extensive ancient history. As early as 4,500 B.C.E., Egyptians employed it to dye the cloth in which they wrapped mummies. The Greeks called it indikon pharmakon ("Indian dye"), coming from the place where the Indus River flows. The Tuareg people of the African Sahara have been known as "the blue people" because they dyed their veils and robes with indigo, which rubbed off on their skin.

Tuareg people in Mali. Photo by H. Grobe.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

The tale about indigo that most delighted me comes from Liberia, West Africa. According to the legend, Asi was the woman who first learned the secret of indigo dyeing. "Hungry for color," she envied the veda bird, which obtained its color by rubbing against the sky. In the time of this story, people could actually touch the sky because it hung so low. They were even able to rip off pieces and eat them. While food filled their bellies, eating sky filled their hearts. Asi reasoned that if she consumed enough sky, it would turn her skin and hair as blue as the bird. Initially, God punished Asi for selfishly wanting the color only for herself. But when she requested that it be available for all her people, the water spirit instructed her in how to dye with the indigo plant. Asi brought back the process to her village. Then, once the women knew how to impart the beautiful blue color to their clothes, God pulled the sky high up and out of their reach. Though the people can longer ingest the sky, they have the color of indigo to satisfy their hearts.

Tuareg men at the Desert Festival, near Timbuktu, Mali (2012).

Photo by Alfred Weidinger. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

I have enjoyed dyeing with indigo in Japan, Korea, and California. I have seen the plants growing on a hill behind an artist’s studio. I have watched a powder made from the leaves being stirred in a huge vat. But I’ve never seen cakes of indigo, like those displayed in a historical collection at the Technical University of Dresden, Germany.

Indigo, historical dye collection of the Technical University of Dresden, Germany. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

While indigo dyeing can produce gorgeous patterns on fabric and paper, it can also leave one’s hands looking other worldly if gloves are not worn.

Indigo hands. Photo by Anjora Noronha.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Predictably, at least for me, when I dye with indigo, every piece comes out a different shade of blue.

Floating in a Sea of Indigo,

by Mirka Knaster.

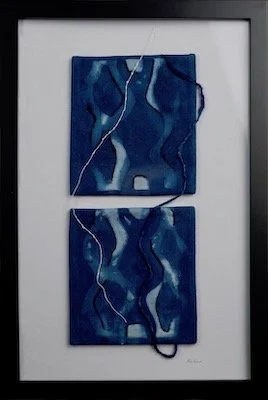

Indigo Ice, by Mirka Knaster.

Adrift in Indigo, by Mirka Knaster. Combination of linen and Japanese shibori silk.

I learned even more about blue in Michel Pastoureau’s Blue: The History of a Color. It has changed how I view color, for he asserts that it is not only a natural phenomenon, but a strikingly social one as well: "It is society that 'makes' color, defines it, gives it its meaning, constructs its codes and values, establishes its uses, and determines whether it is acceptable or not. The artist, the intellectual, human biology, and even nature are ultimately irrelevant to this process of ascribing meaning to color." He adds that we can too easily and incorrectly project our own contemporary conceptions and perceptions of color onto images and artifacts of the past.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Take blue. During the Middle Ages, it was considered a warm color, but today we label it cool. Centuries earlier, the Romans held it in the lowest regard because it was "the color of the barbarians." Having blue eyes was close to being looked upon as a physical deformity or a sign of bad character. But in the high Middle Ages, blue morphed into an aristocratic, fashionable, and prestigious color, deemed by some as the most beautiful. Today, according to Pastoureau, it is by far the favorite color of Europeans.

Shades of white: white, ivory, platinum, bone, shell, linen, pearl, sand, champagne. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

In some cultures, it is not the color itself that is crucial but the various qualities it can have. For example, in Japan, it's more important to know whether a color is dull or shiny. Consequently, while a variety of white certainly exists in Europe, there are many more words for white--to denote shades from the most somber to the most luminous--in Japanese than in European languages. In sub-Saharan societies, it is more valuable to distinguish whether a color is dry or damp, soft or hard, smooth or rough, joyful or sad than it is to separate red tones from brown and yellow or green and blue. In certain tribes in Benin, located between Togo and Nigeria, the vocabulary for brown is extensive, but it is not identical for men and women. Because of this diversity, it would be interesting to hear the responses of people from different cultures to colors seen in paintings, tapestries, and wearable art. What words would they use to describe them? Would one see “sad” while another sees “gray,” “damp” rather than “red”? How much does one’s environment and climate color how we observe colors? As Pastoureau concludes: "Color is not a thing in itself, much less a phenomenon related only to sight."

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

After Pastoureau's history of blue, I'm curious to go beyond the delight I experience in seeing and feeling a color. I can’t help but think that I’ve taken color for granted in some ways, made certain assumptions that were perhaps influenced by cultural norms. When viewing all kinds of art now, I wonder what the people who created them thought of the colors they worked with during their particular era. How differently might I interpret or understand their art were I knowledgeable about the meaning and status those colors held then, compared to how they're appreciated or depreciated in our own time? And how did those colors come to exist: through minerals, plants, creatures? It’s definitely a vast field to explore in the world of art.

Question & Comments:

What are your favorite colors? Do you know the stories behind them? Has your favorite color changed during the course of your life, just as it has during human history?

What colors do you associate with particular cultures or geographical areas? Why do you think those colors are specifically there?