The Wonders of Fiber Art

As someone who is familiar with the work of the most acclaimed fiber artists, I was delighted when a friend sent me a link to a New York Times article (9/11/23): “Fiber Art Is Finally Being Taken Seriously,” by Julia Halperin. It celebrates the pioneers as well as newcomers. But I can’t help but ask: Well, seriously taken by whom? Lots of people have taken fiber art seriously for decades, even millennia. Yet it seems that only when major institutions deign to give recognition is there a measure of acceptance. I agree with Halperin’s assessment: “Now, as the art world reckons with just how narrow its conception of artistic genius has been, the hierarchy placing art above craft — and intuition above skill — looks ever more gendered and archaic.”

Sebastopol Center for the Arts, Sebastopol, California

Still, even without her encouraging words, I knew it would be very worthwhile to visit International Fiber Arts XI at the Sebastopol Center for the Arts (July 29-September 10). As a board member of the Textile Arts Council (Fine Arts Museums, San Francisco), I arranged to have a guided tour of the exhibit with one of the jurors, Judith Content. A full-time studio artist for almost 35 years, she has exhibited nationally and internationally and has work in museum, public, and private collections.

Intaglio, by Judith Content. Silk, hand-dyed and machine stitched

Judith graciously accepted my request to be at the biannual exhibit and describe to our group how she and the other juror, textile artist Ann Johnston, engaged in the selection process. Curiously, after four days of separately reviewing hundreds of submissions from around the world, they both came up with the same 200 pieces. But then they were told to whittle down to between 60 and 80. Dealing with size limitations, they finally settled on 62.

In her juror’s statement, Judith wrote that “it was a daunting job to create a wide ranging but cohesive exhibition.” Ann added, “Of course, we had hard decisions to make, choosing from so many entries. It required looking at all the pieces over and over and trying to imagine the actual art from the images and how they would look in-person at their actual size. We read the artist statements over and over also, trying to understand what was being said….My goal was to pick pieces that were excellent in design and execution and had a cohesive underlying concept. I looked for pieces that would have an impact on the viewer, and we were offered many of those that succeeded in completely different ways.” Both of them thanked Joy Stocksdale and Kathryn Davy for their guidance.

While I learn a lot from hearing how jurors narrow the numbers, I know that this is a subjective exercise. If you’re an artist whose work was not in the show, the only thing I can say is that jurying is arbitrary. Two other jurors might have opted for a completely different combination of pieces.

Because texture is key to fiber art and best viewed on site, I have included detail shots in the hope that they will give you a better sense of the artwork and why the jurors selected them. All photographs are mine.

Release, by Carolyn Burwell. Monofilament, handwoven and dyed.

Detail of Release, by Carolyn Burwell.

International Fiber Arts XI is billed as “presenting a distinct approach to innovative and traditional fiber techniques, and contemporary concepts for the use of traditional and unusual materials.” It includes both 2-D and 3-D pieces as well as wearable and installation art. That gives you an idea of the parameters within which the jurors made their ultimate decisions. As is evident in the two images above, while monofilament may not fit our traditional definition of fiber, it is being used to create an unusual weaving, one which perhaps pays tribute to Kay Sekimachi’s monofilament tubular woven forms.

Releasing the Spirit, by Sue Weil.

Cotton warp; wool, cotton, tencel weft.

Detail of Releasing the Spirit, by Sue Weil.

But that doesn’t mean traditionally woven items are not chosen. Sue Weil wove Releasing the Spirit on an upright loom, which didn’t allow her to see what she was creating. When she took the piece off the loom, she realized she wasn’t happy with it. So she began to open it up by unraveling. The jurors were intrigued by how that gave more meaning and nuance to the yarn.

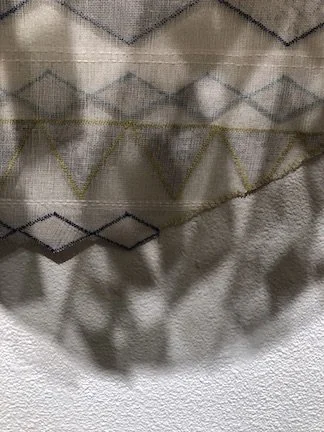

Diamond Cape, by Christine Meuris.

Bookbinding cloth, kozo paper, sumi ink, and thread.

Detail of Diamond Cape, by Christine Meuris.

Christine Mauris won First Place for her Diamond Cape. Judith commented on the qualities of this work: that shadows create more contours, increasing the overall dimensionality; that the use of color is subtle; plus outlining and geometric shapes add movement. She said, “It feels ethereal but powerful. A cape is intended for protection, but this piece is too fine, too see-through, to be physically effective. Instead, it is intended as a protective cape in other realms.” Because the bookbinding fabric (mull) Mauris employed is already stiff, no starch or similar product was needed to hold the shape.

Stone Henge, by Jeanne Reisman.

Open weave linen, organza, and threads.

On the other hand, Jeanne Reisman did use a stiffening agent (Powertex) on linen to make her pieces stand upright. Stitch Henge won a Juror’s Award.

Detail of Stone Henge, by Jeanne Reisman.

Sometimes, what captivates the attention of jurors is the kind of material the artist used. For example, Gray Caskey created Nimbostratus with reclaimed landscaping fabric. The curves that cast shadows constitute another interesting element. The title got me wondering, so I looked it up: “a type of cloud forming a thick uniform gray layer at low altitude, from which rain or snow often falls (without any lightning or thunder).”

Nimbostratus, by Gray Caskey.

Reclaimed landscaping fabric, fasteners, wood.

Detail of Nimbostratus, by Gray Caskey.

Elaine Unzicker created a different kind of kimono-inspired piece, Encompassing. Like Gray Caskey, she worked with unusual material—stainless chain mail—in a painstaking way.

Encompassing, by Elaine Unzicker.

Stainless chain mail interlocked one ring at a time.

Detail of Encompassing, by Elaine Unzicker.

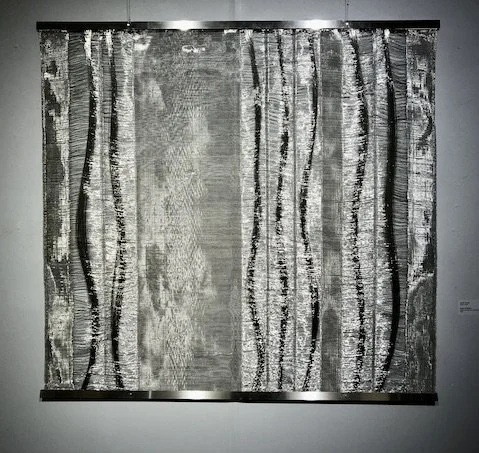

Kyoko Kumai also worked with metal in her weaving, Road of Water. The silvery sheen imparts a sense of fluidity and looks like gossamer silk. Judith noted the importance of light in this piece and the Japanese aesthetic of beauty in shadow patterns.

Road of Water, by Kyoko Kumai. Stainless steel lines, stainless steel bars.

Detail of Road of Water, by Kyoko Kumai.

Cross-stitch is such a basic technique, yet it can have a striking effect. Diane Meyer took thousands of images of where the Berlin Wall had once been erected while walking and looking for clues to find that ground. She applied 30,000 stitches onto this one photo image to allude to what used to exist.

Reichstag, by Diane Meyer. Hand sewn archival ink jet print.

Detail of Reichstag, by Diane Meyer.

At one point, Judith asked Barbara Shapiro, a tour participant, to talk about her entry in the exhibition. Barbara said it’s a response to destruction of the environment that’s partially due to the fashion industry. According to a report by the United Nations Environment Programme, “fashion accounts for up to 10% of global carbon dioxide output—more than international flights and maritime shipping combined…[and] for a fifth of the 300 million tons of plastic produced globally each year.“ To reflect that a lot is twisted in our society, Barbara made five twisted cubes out of designer shopping bags she has saved for decades. A sixth box lies on its side, split open, with its dirty secrets spilling out.

Faulty Towers: No Waste Fashion and the Inside Story, by Barbara Shapiro. Twisted cubes plaited from designer shopping bags, sumi ink stained packing paper, glue.

In Bleached, Ruth Tabancay is pointing to the dire state of coral around the world. Increased ocean temperatures and changing ocean chemistry are the greatest global threats to coral reef ecosystems. Warmer atmospheric temperatures and increasing levels of carbon dioxide in seawater are causing these threats. Ruth crocheted stylized reef structures and interspersed them with plastic medical waste. Over a nine-year period, she collected the plastic detritus while going through treatment for a chronic medical disease.

Bleached, by Ruth Tabancay. Yarn, needle caps, vial caps, tubing caps, oxygen tubing, polystyrene, pins.

Detail of Bleached, by Ruth Tabancay.

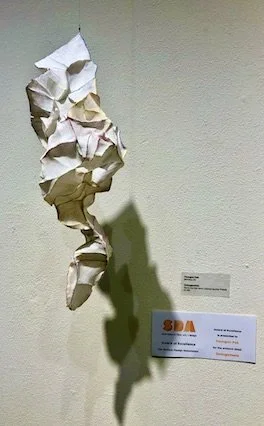

Youngmi Angela Pak won an Award of Excellence from the Surface Design Association for her bojagi-inspired textile sculpture.

Ontogenesis, by Youngmi Angela Pak.

Hand-stitched ramie and silk with colored sewing threads.

Detail of Ontogenesis, by Youngmi Angela Pak.

Although so many artworks are worthy of viewing and commenting, I clearly can’t include all 62 in a blog post. I’ll close with a series of images to reflect diversity of materials and construction methods. Like jurying a show, it’s a challenge to narrow down to a few photographs when it would be great to see everything, especially if you didn’t get to go to the exhibit. I do not mean to offend the many artists whose work is not included here. In some cases, the photographs I took simply don’t do their art justice.

May this minimal selection pique your interest in attending a fiber art exhibit wherever you live or travel. And, if you’re a fiber artist, feel proud to be one!

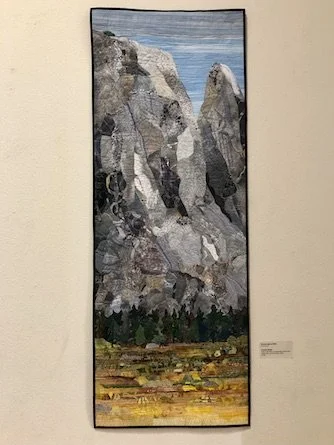

Granite Walls, by Denise Oyama Miller. White cotton fabric, commercially printed cotton fabric, eco felt batting.

Detail of Granite Walls, by Denise Oyama Miller.

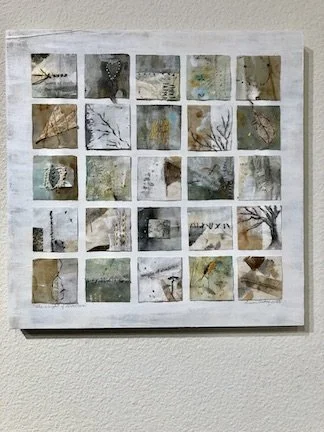

Incrementum I, by Briana Babani. Paper, wool and cotton yarns.

Detail of Incrementum I, by Briana Babani.

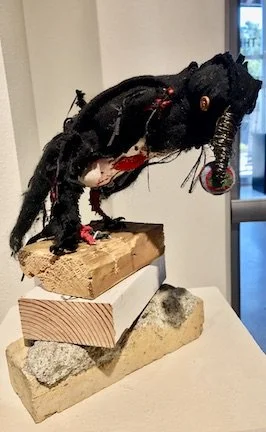

Keeper, by Julia Feldman. Repurposed fabrics, found objects, hand embroidery.

Winnow, by Vesna Breznikar. Vellum, bronze wire, willow branch, string, plywood, paint, shellac. (Juror’s Award)

Detail of Winnow, by Vesna Breznikar.

And the World Fiddled While the Planet Burned, by Judith Plotner. Unsized canvas, paint, thread, pellon. (Coordinator’s Award)

Detail of And the World Fiddled While the Planet Burned, by Judith Plotner.

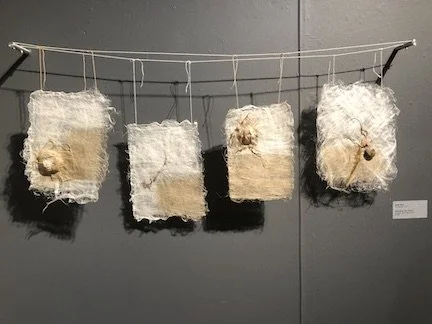

Emerging Life Forms, by Molly Wertz. Flax fiber, cotton yarn, thread.

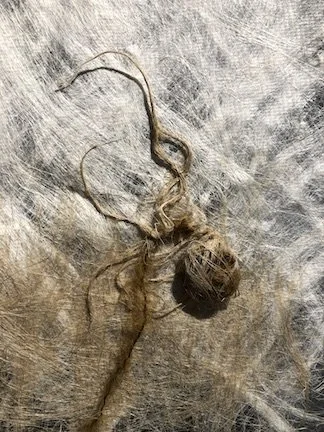

Detail of Emerging Life Forms, by Molly Wertz.

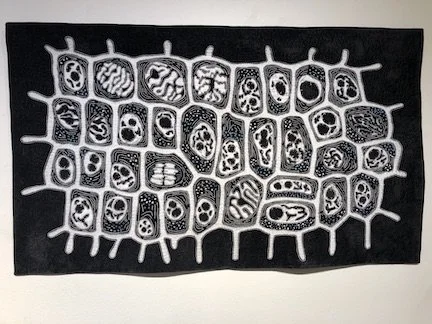

CELL-evision, by Kathy Suprenant. Large hand-carved woodcut printed on silk velvet, free hand stitching, quilt.

Detail of CELL-evision, by Kathy Suprenant.

The Weight of Shadows, by Susan Audrey. Handpainted, hand-dyed, handstiched fabric and found objects on cradled birchwood canvas.

Detail of The Weight of Shadows,

by Susan Audrey.

Colors of Morocco—Chefchaouen, by Yasuko Okumura. Pigment ink on silk organza, wool roving, hand-leno woven, aluminum.

Detail of Colors of Morocco—Chefchaouen,

by Yasuko Okumura.

FIT, by Marie Bergstedt. Wool, rayon, cotton, acrylic, silk, chenille, buttons, needlepoint canvas.