Starting 2024 with Fiber Art

Erin Algeo standing next to Rainbow Over Lanai (2007) during a Textile Arts Council tour at The San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles

During my childhood, going to the movies usually meant seeing a double feature. Nowadays, you’re more likely to get a Twofer only when visiting museums. That’s the opportunity we had during a Textile Arts Council tour at The San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles (SJMQT). On the last day of two exhibits, we viewed and learned about Hawaiian quilts as well as about a diverse grouping of 2-D and 3-D fiber art. We were privileged to have Erin Algeo guide us through Maui: No Ka’Oi and Demetri Broxton explain how he curated Excellence in Fibers VIII. Their enthusiasm and knowledge made the experience both informative and delightful.

Prince’s Feather Quilt (ca. 1880), signed Hannah.

Detail of Prince’s Feather Quilt (ca. 1880).

Erin grew up on the Big Island and is passionate about Hawaiian culture. (Her efforts made the quilt exhibit come together in response to the devastating fire on Maui.) She described a probable transition from kapa (barkcloth) to quilts. On April 3, 1820, the first quilting bee took place in Hawai’i. A group of missionary wives on the deck of a ship shared the activity with Hawaiian women, who were already adept at making kapa from the paper mulberry plant.

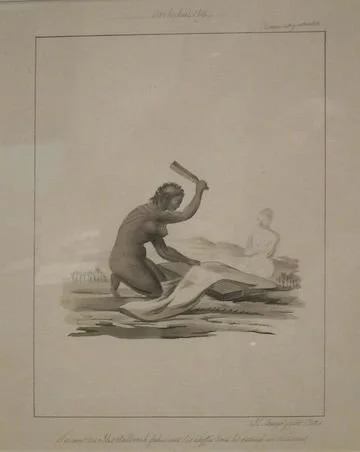

Woman of the Sandwich Islands making the Natural Cloth with which they are Dressed (1819), by Jacques Etienne Victor Arago. Graphite, pen, ink, and grey wash on paper. Honolulu Museum of Art. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

The latter was a laborious process of cutting mature stalks, then scraping the brown and green layers to reveal a fine white layer, the "bast." The bast had to be soaked for up to ten days, after which it was beaten with a mallet and placed in ti or banana leaves in a warm, shady spot to ferment. The fermentation process determined the quality and texture of the finished cloth. A second stage of processing required additional hours of beating, shaping, and stretching the fiber pieces. The kapa cloth was then dyed in various colors with plant dyes and, finally, designs were brushed on. For a bed, there could be seven layers of kapa.

Kapa Kilohana (bark cloth), 19th century. Honolulu Academy of Arts. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Both quilting and kapa making are seriously labor-intensive traditions. While patchwork quilting was conducted as a group endeavor, Hawaiian quilting has largely been a solitary undertaking. Generally, Hawaiian women found inspiration for their designs in the natural environment. A paper-cutting technique is still used to create a design, rather than cutting up fabric into small pieces to be sewn together (patchwork). The shape of a flower, plant or fruit is appliquéd in a bright solid color against a white or otherwise pale background.

Patterned shapes for Hawaiian quilts.

However, over time, quilters have branched out with different hues and patterns. Even in the nineteenth century, there were also quilts representing the Hawaiian flag.

Ku’u Hae Aloha (My Beloved Flag) in foreground (1889); reproduction on the wall.

Erin explained that, after the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown by Americans in 1893, flying the Royal Hawaiian Flag was considered an act of treason. In resistance, Hawaiian quilters started to incorporate the flag in quilts and hide them in their homes. The flag quilt lying in the foreground of the above photo was once bright red, white, and blue and contains emblems of the Hawaiian monarchy. A reproduction of it hangs on the wall.

On to the next exhibit.

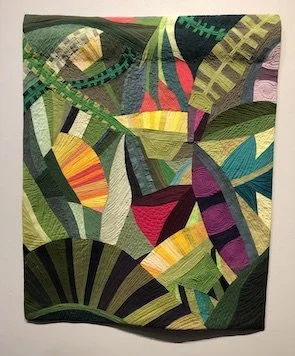

Botanicals 2 (2021), by Jean Howard. Hand-dyed and commercial cotton fabric, batting, thread; machine-pieced and -quilted.

Excellence in Fibers is an annual, international juried fiber arts competition organized by the Fiber Arts Network. Given that there are different submissions and jurors each year, it’s hard to predict what will be on offer. As we entered the large gallery to view Excellence in Fibers VIII, Demetri explained that there had been hundreds of submissions, juried down to 40, out of which he selected 14 for SJMQT. He chose those pieces that resonate with him aesthetically and because the artists use fiber art to interrogate important issues as well as represent diverse backgrounds, media, and geographies. The range was impressive.

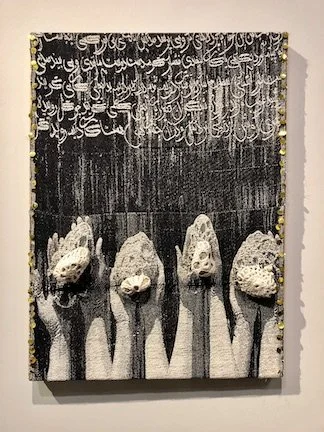

Woven Journey (2022), by Katayoun Bahrami.

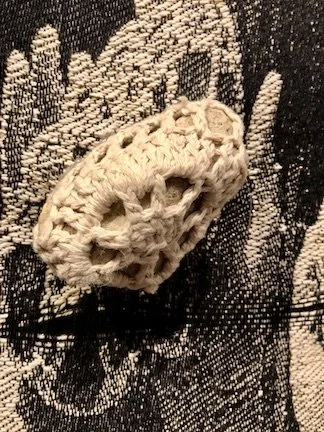

Iranian artist Katayoun Bahrami combined cotton and metallic yarns, stones, beads in Jacquard weaving and crochet to create Woven Journey. It is based on a painting she made following the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan, juxtaposed with stones from her project Quest. Her statement indicates that she strives “to amplify women’s voices,” examining “the intricate relationship between women and their identities, interwoven within religious and political histories,” confronting “misogynistic laws in Iran” and evoking “emotions surrounding exile and borders.” Think: stoning women. According to the international group Women Living Under Muslim Laws, stoning "is one of the most brutal forms of violence perpetrated against women in order to control and punish their sexuality and basic freedoms."

Detail of Woven Journey (2022), by Katayoun Bahrami.

Mee Jey states that, as an artist and a mother, her “understanding of ‘journeys’ and the idea of ‘home’ has changed significantly” since immigrating from India to the U.S. Feeling vulnerable, “on the fringe of political priorities and financial systems,” she is also optimistic about “a better life and time.” She created Brave Wave Rider by cutting recycled fabrics into long strips, twisting them to form rope, then pasting them on a wooden board.

Brave Wave Rider (2022), by Mee Jey. Repurposed fabric on wood board.

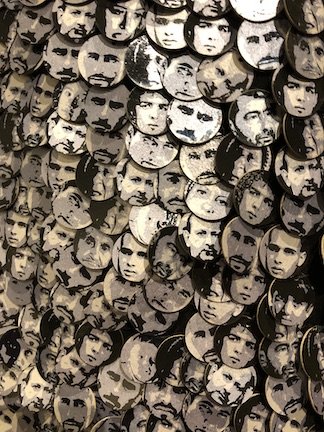

When Demetri stopped to talk about Andi Arnovitz’s Heavy, I moved in to look more closely. What I thought were, at a distance, thousands of sequins turned out to be tiny cardboard circles. Each disc is imprinted with someone’s face and represents not just that person, but ten women, men or children. Arnovitz, an Israeli artist, says that her “textile infographic” explains “the magnitude of loss of civilian life in the ongoing Syrian Civil War.” Because the regime did not distinguish between combatants and civilians, bombing and chemical warfare destroyed entire villages and killed more than half a million people.

Heavy (2022), by Andi Arnovitz. Black linen, digitally printed board with lacquer and threads; hand sewn.

While the work looks like an elegant ballgown, Arnovitz explains that it is a shroud on which the discs get darker with each year of the civil war: “The numbers mount, weighing down the piece.” It is sobering to reflect on the powerful impact of Heavy.

Detail of Heavy (2022), by Andi Arnovitz.

Detail of Heavy (2022), by Andi Arnovitz.

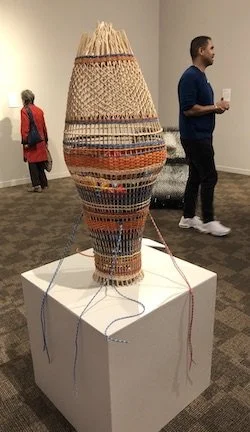

Fish Trap, by Lynn Dees of Texas, is part of a three-dimensional series based on indigenous traps to catch fish, crab, eel, and lobster. She incorporates “the concepts of trapping, captivity, isolation, censorship, and imprisonment to illustrate current human conditions, relationships, and current events.” Dees incorporates recycled objects to illustrate the extent of waste we humans produce. But she also makes us aware of how recyclables can be used “to create works that are playful and have personal meaning.” She lashed, knotted, twined, wove dyed and natural rattan, and placed plastic caps inside.

Fish Trap #2: Catch o’ the Day (2020), by Lynne Dees.

Detail of Fish Trap #2: Catch o’ the Day (2020), by Lynne Dees.

Hattie Lee, of Illinois, considers her weaving practice an expression of the Cherokee Diaspora. She uses found bright, non-traditional materials and also designs original compositions that reference such influences as “a variety of cultures, personal narratives, and friends and family who have shaped [her].” She sees her weaving as representing “the joy of culture and heritage, the joy of our increasingly diverse world.”

Corona Crazy (2022), by Hattie Lee. Bias tape, ribbon, and lace on stretcher bars.

Detail of Corona Crazy (2022), by Hattie Lee.

Terrain, by Sugandha Gupta, is the epitome of why people like to touch fiber art. Born and raised in India, but now living in New York City, she is visually impaired with albinism. She creates her work with a broad audience in mind, expecting people to have a sensory experience—to touch, see, hear, and smell. She says this particular piece is “an abstract representation of how I see, and my insights from interactions with other blind and visually impaired folks.” Gupta’s textiles and wearables are inspired by her “encounters in nature” and her “navigation of the world.” She employs natural colors and fibers in an effort to reflect the hues of albinism. Her intention is “to bridge the gap between the mainstream and disabled communities.” In Terrain, she incorporated wool roving, silk roving, wool yarn, beans, pebbles, string, which she felted, embroidered, sewed, and couched.

Terrain (2022), by Sugandha Gupta.

Detail of Terrain (2022), by Sugandha Gupta.

SlipCover, by Ruth Shafer, of Vermont, was an unexpected part of the exhibit, but intriguing as a unified monochrome object. I remember slipcovers from my childhood as a means to protect furniture from wear and stains and also to conceal threadbare patches. In Shafer’s piece, a female form is both separate from and blended into a slipcover that matches the winged armchair in which she sits. The artist describes the sculpture as confronting, with “quietude and poise,” the dualities of domesticity: “safety vs. confinement, identity vs. decoration, opportunity vs. obligation.” Committed to using secondhand fabric and repurposed fluff, she took apart one of two found armchairs for its textile in order to create the female form sitting in the other chair.

SlipCover (2022), by Ruth Shafer.

What a surprise to see yet another chair in the exhibit. Theda Sandiford, lives in New Jersey, but travels often to the Caribbean, where one side of her family comes from. That means her work needs to be portable and can even be rolled up. Demetri explained that SJMQT was required to buy a lounge chair over which Sandiford’s “blanket” would fit, which was far less expensive than shipping from the east coast. In addition to the white leather chair, there are 4-inch zip ties and recovered knotted fishing net. Techniques include knotting, draping, and photography.

Blackity Black Blanket (2020), by Theda Sandiford.

Sandiford considers Blackity Black Blanket “aesthetic armor to shield myself from racial trauma.” Intentional or not, she finds racial gaslighting triggers self-doubt and circumvents uncomfortable discussions about race. She notes its impact: “The constant questioning of what I know to be true has affected me, manifesting in insomnia, anxiety, and emotional baggage.” Do you see the silhouette of a body under the blanket?

Detail of Blackity Black Blanket (2020), by Theda Sandiford.

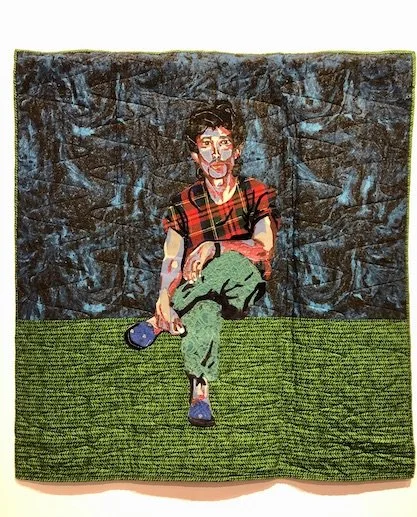

Anna K. Betts, living in Tennessee, pays homage to her cultural background in In-Between. A child of the Laotian diaspora, she reflects on making a new home in America while assimilating to its cultural norms. Like other refugees fleeing from war, her family “was stripped into pieces of broken identity.” In utilizing Western quilting methods, Betts finds the act of stitching symbolic of how one can hold close and bond with one’s heritage. For In-Between, she worked with fabric, cotton batting, felt, fabric glue, heat bond and, of course, thread to tie together past, present, and future into a new whole.

In-Between (2022), by Anna K. Betts.

Detail of In-Between (2022), by Anna K. Betts.

Two entries in Excellence in Fiber VIII took up a lot of room—an entire long wall or gallery—and rightly so. In his role as curator, Demetri did something that really appeals to me: he gave the works plenty of breathing space. This allows a viewer to take in and appreciate artwork in a quieter manner than in salon-style hanging, where every square inch is covered with paintings. That’s too dizzying for me: I can’t see the individual trees in the forest.

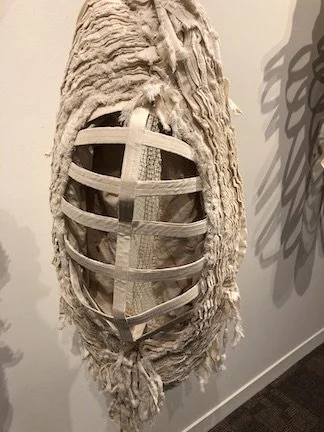

Evolvo (2023), by Tina Marais Struthers.

Living in Québec, Canada, Tina Marais Struthers binds, folds, and pleats cloth. For Evolvo, she worked with linen and hemp, embroidery thread, and stitched by hand and machine. She writes: “Folding and unfolding is an act of care, a passage of time, a ceremony, a structured linear process of covering and revealing. Fragile scarred skin covers the memories of entwined things. Bodies have become vessels for interlaced narratives, unraveled, revealed. There is an inexhaustible tension between weft and grain, between the human and non-human webbing of emotional elasticity as I map the entangled memories of territories and matter. The cloth of things can be torn, the skin of things can be stretched too thin.” The individual pieces feel like skeletons of beings whose identity I can’t guess.

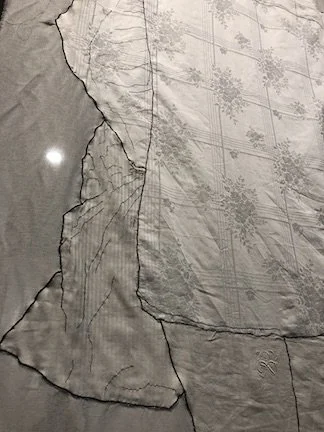

While there are a few more items included in the exhibit, I’m going to end with what we were led to at the end of the tour. You May Recognize Yourself, by Kerstin Bruchhäuser, from Germany, is an amazing textile installation. Although it actually comprises 58 larger-than-life sewn portraits of women, only a portion of them were part of the show at SJMQT. Bruchhäuser took photographs of contemporary female figures only from the back as she saw them walking, running errands, going to the gym, meeting with friends, and checking their mobile phones. She wanted to raise questions about “individuality, identification and self-determination.” Until Germany passed the long-overdue Equal Rights Act of 1958, there was still a legal textile tradition of dowry. At marriage, young women were supposed to receive a complete set of bed linens, tablecloths, napkins, towels, etc. But, from then on, parents were instead required to provide their daughters with professional opportunities to insure financial independence. Quite a societal change, and the sheer size of the portraits and the installation demonstrates that.

You May Recognize Yourself (2022, ongoing), by Kerstin Bruchhäuser

Each portrait (approximately 40 inches by 140 inches) is fabricated from different pieces of antique dowry (cotton, linen, silk) and sewn together with appliqué and embroidery.

Detail of You May Recognize Yourself (2022, ongoing), by Kerstin Bruchhäuser

Touring exhibits with those involved in the curating and installation is always a treat. Both Erin and Demetri delighted us with anecdotes that were enlightening and sometimes even humorous, more than I can share here. The next time the opportunity arises to view an exhibit in this way, I highly recommend taking advantage of it.