When Is It Done?

Something every creative person faces is imperfections. Whatever we create is going to have them, no matter how hard we try to make it perfect. This begs a host of questions: Then how do we know when a work of art is finished? And who says it is? Is anything ever truly finished? When do we stop experimenting and reworking before we’ve overworked a piece? Whether we're involved in literature, theater, music, dance, painting, sculpture, ceramics, or fiber art, are we ever totally done with a poem, play, symphony, tapestry, novel, or collage, even after it has been exposed to the public? As visual artists, writers, composers, or choreographers, we're constantly evolving, so why wouldn't our creations also keep evolving, even if only subtly? One of the women in a monthly art salon I participated in years ago told us that, according to a biography of Shakespeare she’d read, he kept revising till the very end of his life.

In the image below, did Leonardo da Vinci intend to complete this self-portrait or was it meant to be a minimal sketch?

Presumed self-portrait by Leonardo da Vinci

(c. 1510). Royal Library of Oxfordshire.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

This topic has occasionally been featured in the art world. For instance, in 2016, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art had an exhibition called Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible. It dealt with a crucial aspect of artistic practice—how and when we determine a work of art is done. The show included works that, for whatever reason, were left incomplete by the artists, affording us a glimpse into their creative process. It also embraced works that were intentionally unfinished (non finito), "an aesthetic of the unresolved and open-ended" that painters such as Rembrandt, Titian, Cézanne, and Turner explored. Then there are the modern and contemporary artists who did not demarcate between making and un-making, and even left the "finishing" to viewers. The Met cites Janine Antoni, Lygia Clark, Jackson Pollock, and Robert Rauschenberg in that group. In the case of American artist Kerry James Marshall's untitled work below, is the viewer being invited to complete the painting by filling in the numbered areas behind the female artist?

Untitled (2009), by Kerry James Marshall.

Image Copyright Yale University Art Gallery, 2009.

By current standards, artwork from hundreds of years ago might not appear incomplete to us because their treatment would make a different statement in the 20th or 21st century than that of detailed realism in the past. El Greco's The Vision of Saint John, a fragment from a large altarpiece made for the church of the hospital of Saint John the Baptist in Toledo, Spain, is a good example. In the 17th century, the painting seemed unfinished, but not so now.

The Vision of Saint John (1608-1614), by El Greco. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Do the various images in this post appear incomplete to you? Would you rather the artists had finished them or do you enjoy imagining what they would be like? Do you find yourself inserting details? I consider some of the incomplete portraits far more interesting, for they seem to convey moods that might not otherwise come across as distinct when there is much else to view in the painting. In portraits left unfinished except for the face, the focus and, thus, our attention certainly shifts.

Sir Joshua Reynolds was the leading English portraitist of the 18th century. Among his two thousand paintings, I found one that is clearly unfinished, Portrait of a Young Man (ca. 1770). Was that intentional or was the young man unable to continue sitting? Perhaps a biography of Reynolds explains what happened.

Portrait of a Man, probably Francis Barber (ca. 1770), by Joshua Reynolds. Photo by Hickey Robertson.

The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas.

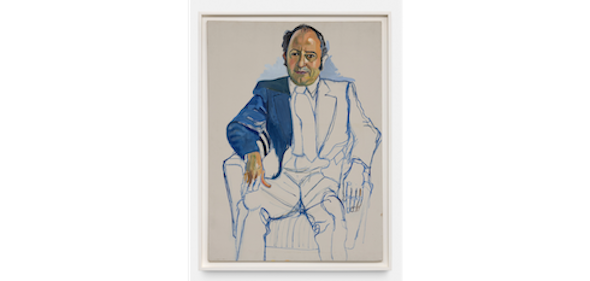

We do know what interrupted a portrait that American artist Alice Neel was working on. The young African-American man in New York was drafted to fight in the Vietnam War and, presumably, never returned. Yet another one of her portraits is unfinished, but I don’t know why.

Dr. Lucca (1974), by Alice Neel. Source: artsy.net

Sometimes a work of art is abandoned due to ill health. According to the Met's notes, Juan Gris once expressed a "desire to find a more sensitive side in his art, one he associated with the freedom and charm of the unfinished." The underdrawing in the work below reveals how Gris constructed his composition geometrically. But he added his personal take on Cubism with such curvaceous elements as the oval shape of the upper body and the flowing black lines. It was not his intention to leave the reading woman incomplete. It was failing health that stilled his hand. Nevertheless, the painting has an intriguing charm just the way it is, as though we’re peering through an X-ray.

Woman Reading (ca. 1927), by Juan Gris. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

And sometimes it’s death that leaves an artwork unfinished. Gustav Klimt never completed his posthumous portrait of Maria ("Ria") Munk III. While working on this third attempt at portraying the woman who committed suicide because her fiancé broke off their engagement, Klimt himself died. As with Gris' painting, what remains demonstrates the artist's process.

Posthumous Portrait of Ria Munk III (1917-1918), by Gustav Klimt. The Lewis Collection, The Met Breuer, New York.

Particularly with some expressions of modern art, how is anyone to decide when a painting or sculpture is done? Unless Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti wanted to change the feeling in this portrait of his wife Annette, isn't it complete as a reflection of a dark, perhaps troubled state?

Annette (1961), by Alberto Giacometti. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, The Met Breuer, New York.

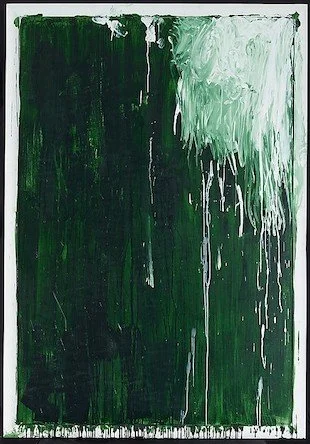

Abstract art is particularly difficult when it comes to deciding when you’re done. Take Cy Twombly’s green paintings. Could there be more paint, less paint? I could ask the same question of Jackson Pollock’s drip works or any number of other abstract artists. At some point, each artist has to decide: OK, that’s it!

Untitled I (Green Paintings) (ca. 1986), by Cy Twombly. ©Cy Twombly Foundation.

Untitled II (Green Paintings) (ca. 1986), by Cy Twombly. ©Cy Twombly Foundation.

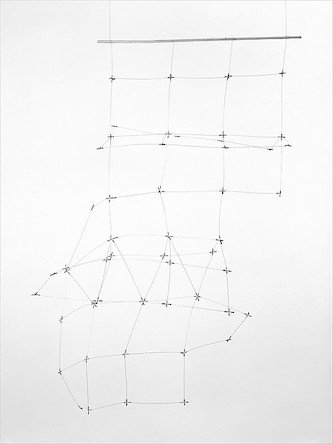

And how did Gego (Gertrud Louise Goldschmidt), a German-Venezuelan visual artist, know when to stop adding more wire? We all develop an inner sense and learn to trust it.

Reticulárea cuadrada 71/6 (1971-1976), by Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt). Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. © Fundación Gego. The Met Breuer, New York.

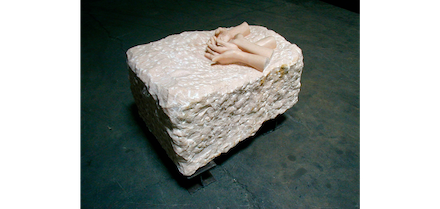

Not everything is supposed to appear whole, especially when the artist has a particular psychological or philosophical reason for presenting incompleteness, as in Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture.

Untitled (No. 2) (1996), by Louise Bourgeois. Source: artsy.net

And in some art traditions, such as East Asian, what looks incomplete to us is actually not that at all. Eighteenth-century Japanese artist Maruyama Ōkyo did not populate the six-panel folding screen with more than one goose. Although nearly empty, the painting does not feel unfinished to me. Looked at closely, the composition conveys a lot about the season and place with minimal brushstrokes.

How we view things has much to do with our upbringing, education, geography, and epoch. What’s incomplete in one area or era might be considered complete in another. In 2018, I visited the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno to see an exhibition by Aboriginal women artists in Australia. I am sorry I don’t have their names. In the detail images of two paintings, unlike in certain East Asian aesthetics, it’s obvious that no space is left unfilled. Because there is no written language for Aboriginal People, they convey their important cultural stories through their artwork. I’m guessing that empty space would reflect an incomplete narrative or mapping.

Detail of painting by Aboriginal woman in Australia.

Detail of painting by Aboriginal woman in Australia.

So how do you know when to put down your needle, paintbrush, carving tool, shuttle, or pen? How do you decide it’s time to get up and walk out of the studio? Are you finished because the work has been displayed and sold? Or is it simply a matter of finally feeling satisfied? For each artist, something different will signal completion. And, for some, it might never come and have to be imposed. Take your pick. Become familiar with your own rhythm and when you reach the coda.

Question & Comments

How do you deal with the issue of completing your own artwork? When do you know you're done?

When you look at art, do you reflect on whether it is complete or incomplete? Do certain artists trigger a particular reaction one way or the other?

Do you sense the difference in what is complete/incomplete in art of cultures that are not your own?