Racism, Sexism, Ageism in the Art World

Our world abounds with -isms (systems, philosophies, ideologies) and -phobias (extreme fear of or aversion to something): sexism, racism, antiSemitism, ageism, homophobia, Islamophobia, xenophobia, isolationism, nationalism. Who among us hasn’t experienced at least one of them during our lifetime? How about in the art world?

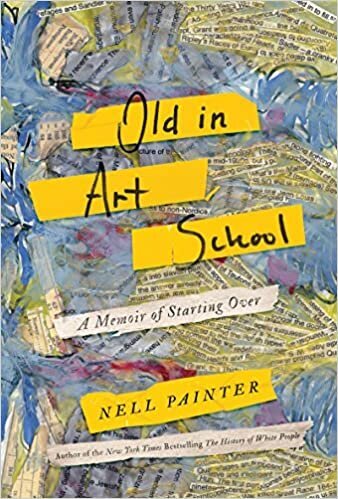

Barely a week ago, three artist friends and I had a Zoom discussion about Nell Irvin Painter’s Old in Art School. The memoir reveals her striking encounters with racism, ageism, and sexism in her journey to become an artist. Her sterling professional credentials—she is distinguished Edwards Professor of American History Emerita at Princeton University, author of six other books, many essays, reviews, and articles, and recipient of multiple honorary degrees and awards—isn’t what others noticed about her. Indeed, these facts were held against her. We may think that, by this point, the art world would be free of negative -isms, but it ain’t so.

Source: nellpainter.com/

Renowned for her work on U.S. Southern history, Painter decided to go back to school at the age of 64. While others retired, she entered Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University for her BFA, followed by the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) for her MFA. The first question everyone (that is, everyone much younger) unconsciously blurted out upon meeting her was: “How old are you?” They might as well have said, “What the heck are you doing here, grandma?” She didn’t let that stop her. In fact, no matter what challenges she came up against, Painter was determined to keep going. But it was certainly tough going.

Nell Irvin Painter. Source: twitter.com/painternell

Though highly confident as a notable academic, in art school Painter was suddenly a nobody riddled with doubts and insecurities. Her skills and values as a historian were suspect, even dismissed. She was repeatedly criticized: “You can’t draw. You can’t paint. Your work is illustration.” That just made her work even harder. She was pigeonholed as too “twentieth century.” So she learned the difference between the twentieth and twenty-first centuries perspectives on art and adapted. She was left out when artists and gallerists came to visit students’ studios at RISD. She was not told when a class portrait would be taken so she wouldn’t “spoil” the picture. Hurt and angry, she made them do a second take, in which she was included. And then the sucker punch: “You may show your work. You may have your gallery. You may sell your work. You may have collectors. But you will never be An Artist.” Talk about mean-spiritedness!

Nell Irvin Painter. Photo by John Emerson. Source: www.washingtonpost.com/ (July 17, 2018).

As an African-American woman, Painter was stopped when she entered a building to work one night. The person who questioned her silently wondered, “If she isn’t the janitress, what is she doing there?” Well, she was an enrolled student with keys to her studio, that’s what! Her comfortable lifestyle left others baffled because she didn’t fit a stereotype—the poor black. She wasn’t what the white students and teachers seemed to automatically assume: If you’re black, you must have gotten in through some minorities program. Imagine how galling it was that so many people were unable to see her as a person who had just as much right to be there as the rest of them, no matter her skin color, her gender, or her age.

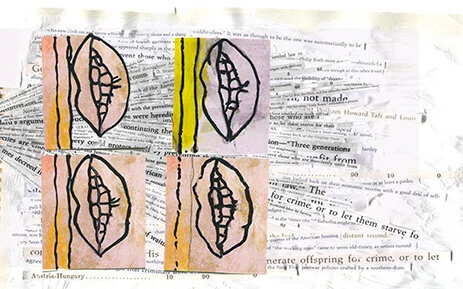

“The History of White People” (2019), by Nell Painter.

Paper and digital collage on foam core. Source: nellpainter.com/

Nevertheless, Painter persevered, finding support and encouragement among friends and professionals outside of school. She explored ways to answer questions that arose: How to deal with dark skin in figurative art when there are no such models in art school? She made herself the model and created self-portraits. Why are no African-American artists discussed in class? Because they’re not part of the curriculum (just as women artists weren’t included in the textbook I used when I was a university student). She gave herself a crash course in African-American art history and learned about “entire worlds of interesting art that were not visible in the art history” she studied at Rutgers and RISD

Then there were questions about her personal life. Why fly to California to look after aging and then dying parents, when a real artist does nothing but create art 100 percent of the time? Because, as a loving only daughter, she felt responsible for their care. Why take time from school to go off for non-art-related events? Because she was being honored for her work as a historian. Painter didn’t chop off significant parts of herself simply because she was attending art school. After all, she had a life!

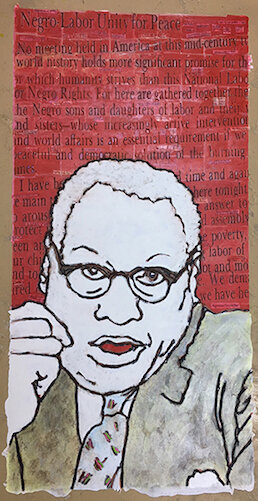

“Paul Robeson Activist” ( 2018), by Nell Irvin Painter. Oil stick, acrylic, and ink on canvas.. Source: nellpainter.com

Painter kept asking: “What counts as art? Who is an artist? Who decides? Why only men, and white men at that?” Her conclusion: “There’s too much good work in the world to explain in terms of quality alone who counts as an artist worth noting and who gets ignored.”

“What I considered discrimination…still pisses me off,” she exclaims. “The art world is racist [and sexist] as hell and unashamed of it…all the while pretending that objective criteria exist.” She adds, “Constructions of American identity equate blackness with community and individuality [a hallmark of being an artist] with whiteness.” In a TV interview on Black America, she said, “It’s exhausting always having to deal with race.”

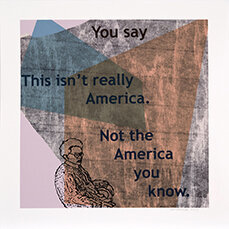

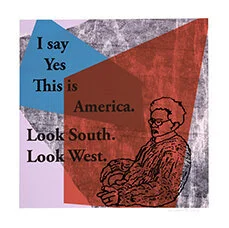

No. 7 of You Say This Can't Really Be America, 2017, digital and silkscreen print on Sunset Cotton etching paper. 17" x 17" each of 8. Published by Brodsky Center, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Collaborating master printer Randy Hemminghaus.

When hung, these two images face each other, along with with six others.

No. 8 of You Say This Can't Really Be America, 2017, digital and silkscreen print on Sunset Cotton etching paper. 17" x 17" each of 8. Published by Brodsky Center, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Collaborating master printer Randy Hemminghaus.

As a result of her own research, Painter’s memoir also introduces readers to a host of African-American artists. Some I wasn’t familiar with, though others I have included in earlier posts. New to me are conceptual artist and philosopher Adrian Piper; sculptor Augusta Savage, who was associated with the Harlem Renaissance; and Charles White, key chronicler of African-American life during the Civil Rights movement, with early-career WPA (Works Progress Administration) murals, just to name a few.

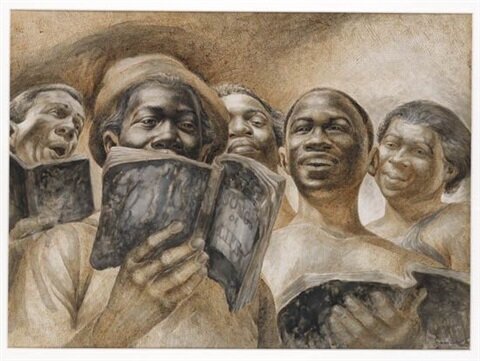

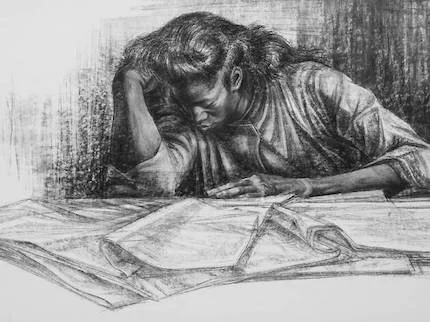

“Songs of Life” (1953-54), by Charles White. Pen and brown and black ink w/gouache additions and ink wash, on illustration board. Source: artnet.com/

From the book cover of Charles White: The Gordon Gift to The University of Texas, by Veronica Roberts. Source: amazon.com/

A souvenir version of Augusta Savage's 1939 sculpture The Harp, which was inspired by "Lift Every Voice and Sing.” 1939 World's Fair Committee. Source: npr.org/

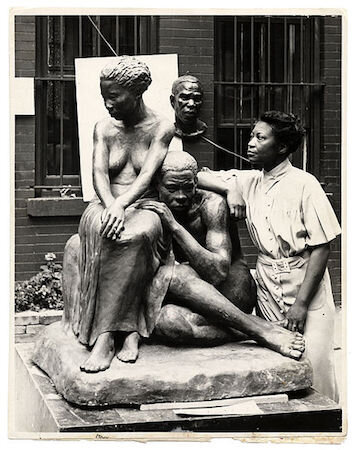

Augusta Savage posing with her sculpture Realization, created as part of the WPA's Federal Art Project (c.1938). Photo by Andrew Herman. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Old in Art School was eye-opening. It begs the question: Is it imperative to get a degree in fine art in order to be taken seriously? If I don’t go to art school am I not entitled to call myself a “real” artist? This opens up a huge conversation. Given Painter’s experience and also that of one friend, I’m glad I decided that I didn’t need a third graduate degree. Yet another friend is grateful for the benefits she derived from her program, but that was 25 years ago.

Despite the prejudices and hard going, in the end, Painter succeeded, but on her own terms. Not only did she graduate, afterward she won fellowships to Yale and Yaddo, among other artist residencies. No, she didn’t become the next “hot, young artist” and is not represented by an elite gallery. But, Yes, her work has been exhibited in both solo and group shows and is in public and private collections. More importantly, Painter learned not to see herself through other people’s eyes, not to let them bring her down a peg. Instead, she learned how to stay centered in the face of what the art world is ready to dish out to an older black woman. “I know the value of doing my work, my work, and keeping at it,” she says. “I am the artist that I am.”

Questions & Comments:

If becoming an artist is a second or third act in your own story, how did it happen? How does it feel?

What discrimination have you faced as an artist, be it for sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion, age or other characteristic?

How well acquainted are you with artists who are not white?