A Beautiful Mess: Women, Rope, Yarn, and Thread

On June 2, fully vaccinated and masked, I had the long-awaited pleasure of experiencing a fiber art exhibit in person. During the pandemic, I certainly saw lots of art online. But physically walking through the spacious, high-ceilinged Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek, California, was entirely of a different order. I was able to viscerally sense scale and texture—for example, the softness or hardness of a piece and the size in comparison to my own body. Passionately curated by Emilee Enders, Bedford’s Curator of Exhibitions and Programs, A Beautiful Mess: Weavers and Knotters of the Vanguard recently ended its run on June 13, after being postponed for a year due to COVID.

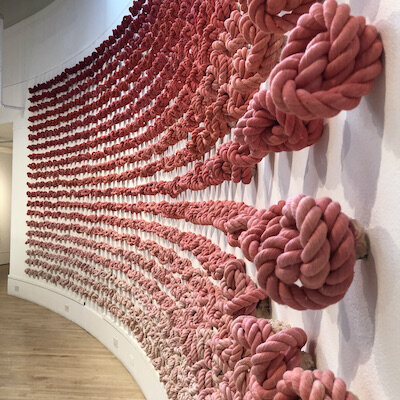

Senninbari (1,000 stitch knot belt), by Lisa Solomon.

Hand-dyed and tied cotton rope.

There is so much to appreciate in this show. Enders intentionally chose women and fiber art because they are both underrepresented in the art world. She carried out extensive research to select the eleven artists. They work LARGE. Many are in the Bay Area. Their creative expression is informed by intense personal stories. Hearing Enders relate those facts made the tour even more evocative. Our group was grateful for her willingness to guide us on a day that the gallery was closed to the general public. Sponsored by the Textile Arts Council of San Francisco’s de Young Museum, the event was a wonderful entrée into the diversity of contemporary fiber art. Kudos to Enders for being its enthusiastic champion!

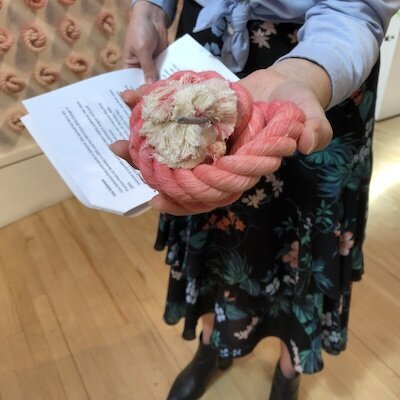

Emilee Enders demonstrating how each knot was affixed to the wall.

Entering the gallery, you can’t help being curious about Lisa Solomon’s huge work. Drawing on the Japanese half of her background, Solomon created Senninbari as a reflection of the folklore belief that the number one thousand (sen) represents good luck. It has been a traditional practice in Japan since the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) to stitch a belt or strip of cloth 1,000 times and give it as an amulet to soldiers going off to fight. Generally, each stitch is made by a different woman, so it’s often a group effort. Because red is considered auspicious, Solomon dyed the cotton rope in an ombre of pink to deep red. Arranged in a grid that spans 122 x 299 inches on a curved wall, the large French knots have a strong visual impact. Each knot is formed from a 2-foot long rope; altogether, there are 2,400 feet of rope.

Orange 2, by Jacqueline Surdell. Braided cotton cord, paint, carabiners, steel curl bar, weight.

As the grandchild of a Polish steel mill worker and a Dutch landscape painter, Jacqueline Surdell, a native of Chicago, embraces both manual and conceptual labor in her art. Her weaving demands full-body movement as she hauls yards of heavy rope that she manipulates across mural-sized looms. Weighing 250 pounds and measuring 96 x 60 inches, Orange 2 is hung from a steel curl bar with a single dumbbell weight at the bottom. For Enders, “these elements recall Surdell’s athletic background [she played volleyball competitively], but they also employ rich juxtapositions between the rigid and collapsed construction techniques coded as masculine or feminine….”

Detail of Orange 2, by Jacqueline Surdell.

In dani lopez’s (she prefers lower case) work, weaving is a physical manifestation for longing and relates to questions of identity, love, and time. Theatrical, glitzy materials reference drag queen culture and the exaggeration of femininity. In her own words, the artist expresses how the weaving becomes “the narrative of an out loud youth…[who] comes from the closeted one I lived…a fictionalized memoir, where I am in control of what is true, what gets rewritten, and where the two become blurred.”

tell me that love isn’t true, by dani lopez. Handwoven cotton yarn and hand-cut novelty fabrics.

Two of the artists, Liz Robb and Meghan Shimek, have used weaving as a way to process loss and grief. Robb created two pieces during a year of “magical thinking,” after her partner died in a motorcycle accident. She mixed beeswax with ash from a ceremonial burning. Weaving, wrapping, and knotting became a kind of catharsis and deep meditation through her period of mourning. The charcoal-colored area in The Phoenix, 71 x 90 x 4 inches, reminds me of gravestone rubbings. The long strands in both The Phoenix and Passage II, 84 x 30 x 4 inches, make me think of the endless tears that flow and spill over from sorrow.

The Phoenix, by Liz Robb. Cotton, beeswax, ash.

Passage II, by Liz Robb. Cotton, grout.

It was the death of her father and separation from her husband that got Meghan Shimek weaving too, including on the floor. She created all five pieces in the exhibit during COVID, gradually shifting from tighter and harder expressions to expansiveness and softness. Wires poking out stand in for such emotions as the shock, fear, and anxiety she experienced early on, before moving toward a life-altering change. The softness in Expand with Me, encompassing a wall at 48 x 210 inches, was made with such soft organic wool that it beckons to be touched. I find it reminiscent of Native American featherwork.

Expand with Me, by Meghan Shimek. Wool, copper.

Detail of Expand with Me, by Meghan Shimek.

Everything Changes, by Meghan Shimek. Wool, wire.

Back in my hippie years, when I made everything by hand, I created macramé plant hangers. But for Dana Hemenway, macramé becomes a subversive gesture to turn craft into innovative sculpture for the world of contemporary art. Thinking outside the box, she has taken the knotting to a place I never even imagined. Hemenway fashions her pieces with colorful extension cords and adds lights instead of greenery. And rather than serve a utilitarian function, the repurposed cords challenge traditional assumptions about design and art.

Untitled, by Dana Hemenway: 42 green extension cords, fluorescent light fixtures, power, wood, hanging hardware. Untitled: 2 pink extension cords, wood, paint, light bulbs.

Detail of Untitled, by Dana Hemenway.

Before launching her studio practice in 2015, Wendy Chien had long careers at Apple and as the proprietor of Aquarius Records in San Francisco. She started by teaching herself a new knot every day for a year. In 86 Knots, we can view some of them. Eventually, that initial learning led to sophisticated large-scale installations that integrate technology, design, history, and linguistics and are based in architectural and digital engineering. Circuit Board is an homage to the years she spent in Silicon Valley. The rust color reminds her of the Golden Gate Bridge. With great attention to detail, Chien takes masculine-dominated elements and transforms them.

86 Knots, by Wendy Chien. Cotton rope, synthetic fiber, satin cordage, acrylic, wood, electric cable.

Detail of 86 Knots, by Wendy Chien.

Circuit Board, by Wendy Chien. Rope, vintage 24k gold Japanese thread, synthetic chainette.

Detail of Circuit Board, by Wendy Chien.

Kirsten Hassenfeld combines salvaged textiles with mixed media. She uses a radial form and weaves from the center point. The shape is an homage to flowers. All the materials are recycled—blankets, wedding dresses, and tablecloths found in thrift shops—and reflect the forgotten labor as well as the histories embedded in them. Hassenfeld accords respect to all those mothers and grandmothers who created these things for others. The woven circles range from 6.5 to 8 feet in diameter.

Millefleur, by Kirsten Hassenfeld. Salvaged textiles, mixed media.

Detail of Millefleur, by Kirsten Hassenfeld.

Multi-racial, Kira Dominguez Hultgren artistically embraces her brownness and deconstructs her family’s postcolonial history in At Least Both Your Parents Are Brown. She created four separate pieces that she then tied together, metaphorically joining the different parts of herself, while examining the classification of race and ethnic identity in the U.S. census. Hultgren engages in a lot of research on various kinds of weaving in different cultures. Her weaving technique in this piece is something she learned from photographic documentation of an unnamed Navajo artist’s woven rendering of the U.S. flag, created circa 1900. The four parts of Hultgren’s work appear as a whole, but structurally they represent brokenness in U.S. history.

At Least Both Your Parents Are Brown (2020), by Kira Dominguez Hultgren. Brown yarn, brown silk, brown leather, brown fleece, brown felt, brown belts, brown fabric, brown wood.

The remaining two artists in the exhibit, though near each other in the gallery, are distinct from one another in material and technique. Katrina Sánchez Standfield, a Panamanian-American living in North Carolina, works with a knitting machine to create brightly colored works that seem to be hyper-sized versions of the potholders we made in elementary school. Because she stuffs the knitted material with poly fill, it’s easy to imagine the fun of squeezing or hugging the 12 x 1.5 feet-tall Repairing.

Repairing, by Katrina Sánchez Standfield. Machine knitted yarn, repurposed poly fill.

Like some of the other artists, Hannah Perrine Mode also makes knots. But unlike them, her 168 knots are formed from clay. In the alcove filled with Rope Team, there is also a video in which she demonstrates how she modeled the knots. The installation recalls the many ways she had to learn how to tie rope as part of a team while working on alpine glaciers and the coastal channels of Southeast Alaska. To traverse the ice fields safely, she had to tether herself to others with lifesaving knotting techniques. Out on the water, she had to use them to dock boats and cast fishing lines. All the knots, though hung separately on the walls, emphasize the importance of interconnecting with others and Nature.

Rope Team, by Hannah Perrine Mode. Unglazed ceramic.

Detail of Rope Team, by Hannah Perrine Mode. Unglazed ceramic.

To see additional pieces by the artists, do go to the Bedford Gallery website and click on the link to the viewing room. If you have a large monitor, you’ll be better able to appreciate the details and understand why we’re experiencing a renaissance in fiber art. It reflects regard being accorded to slowly, even meditatively, making with our hands. It also comes across as a manifesto for repurposing ordinary objects and cast-offs in a spirit of reducing waste and reclaiming their value. Not least, reimagining, reinterpreting, and transforming women’s domestic crafts challenges an art world that is overrepresented by men.

The artists in A Beautiful Mess have gone far beyond the mess incurred by heaps of tangled rope, yarn, thread, and scraps of cloth. There is, indeed, no mess in this exhibit. Instead, there is conceptual and purposeful organization. And there are new ways of working with traditional materials as well as new materials for working in traditional ways.

Questions & Comments:

If you’re a fiber artist, do you work large? How large and why large?

What about these artists and their work intrigues you? Is it their use of materials, techniques, personal/political viewpoint, emotional component?

What other artists are you aware of who turn fibers into striking sculptural compositions?