Sources of Inspiration

Balcony seen from my room at Chopin B & B in Warsaw.

Wherever I go, whether in my daily life or in my travels, I constantly notice shapes and patterns. Even lying in bed, I suddenly observe how one board in the ceiling has long flowing curves, whereas the grain is more striated in the others. It's not that I don't take in the whole scene--the bigger picture--for I do, but my eyes are drawn to these lines everywhere. I find myself taking photos of gates, doors, windows, walls, bridges, floors, sidewalks, manhole covers, and more. Yet I don't necessarily incorporate them into my textile art as such. Except for one project, I've never deliberately used a photo as the basis for a piece. Still, all those shapes and patterns inspire me. Unwittingly, I store them in that visual memory part of the brain. Later, I might express them in some way, but without being conscious of that happening. We don't always know how what inspires us will be translated in our work and even go so far as to change our artistic direction.

Floor at the Museum of the City of Lodz, Poland, formerly the home of the Poznanski family.

St. Patrick's Cathedral. Dublin, Ireland.

I've not written any posts lately because I was out of state and then out of the country for 5 weeks. During that time, I witnessed a great deal of art, but it wasn't until I viewed a special exhibit of American painter and printmaker Frank Stella at the Polin Museum in Warsaw that I started to reflect on the unexpected impact of inspiration.

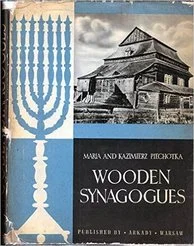

It was, seemingly, the most unlikely of inspirations. In 1970, American abstract artist and architect Richard Meier gave his friend Stella a book of drawings and photographs for his birthday. Published in 1959, Wooden Synagogues, by Polish architects Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka, is a detailed pictorial record of wooden synagogues throughout Poland that were decimated by the Nazis. Why would this lead the son of first-generation Italian-American parents to create experimental, irregular, large-scale, collaged and painted wall reliefs that he named for the towns where Jewish sacral architecture once stood? And how did making them become a turning point in his artistic career?

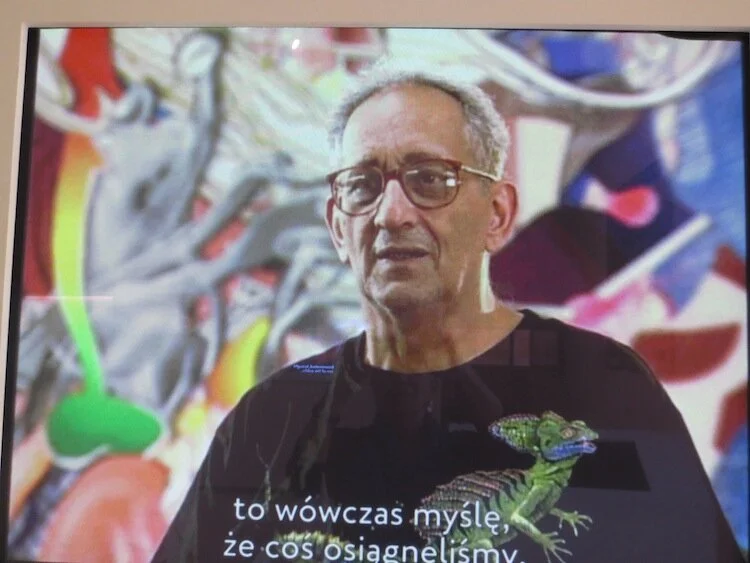

Frank Stella being interviewed at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, October 2002. Photo of video playing at Polin Museum, Warsaw. https://search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?p=frank+stella&ei=UTF-8&hspart=mozilla&hsimp=yhs-002

First, Stella saw in the World War II march of Germans across Poland into Russia the trace of abstraction earlier in the century, recalling the path of Constructivism, an artistic and architectural philosophy that originated in Russia, beginning in 1913, by Vladimir Tatlin, and that influenced modern art movements of the 20th century.

Second, as he "struggled" through the Polish pictures (photos and cross-section drawings), Stella found that they "opened things up for me so that I was able to use my gift for structure with something that modernism hadn't really exploited before, the idea that paintings could be constructed...Building a picture was something natural for me. Build it and then paint it."

Łunna Wola II (1973), by Frank Stella. 97x107x5 in.

Lanckorona I (1971), by Frank Stella. 108 x 90 in.

Stella was so taken with the architecture of the 18th- and 19th-century wooden synagogues that it led to creating his Polish Village Series, an unanticipated new direction. He describes the impact abstraction and the synagogues had on him:

Abstract art developed from Moscow to Warsaw to Berlin and then back the other way and that was the root of the development of abstract art in the beginning--well into the middle of the early 20th century, and that idea of abstraction just stuck in my head and then the actuality of the drawings and how the synagogues were made. I invented a word, I think I invented the word...interlockingness, whatever that means, but it was about the carpentry and about the craftsmanship that went into the joining and building of the wooden synagogues and basically of the structure that was built.

Grodno synagogue: view from the south (1922). Photographer unknown.

In an interview conducted by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Stella goes on to explain how this inspiration resulted in shaping the canvas.

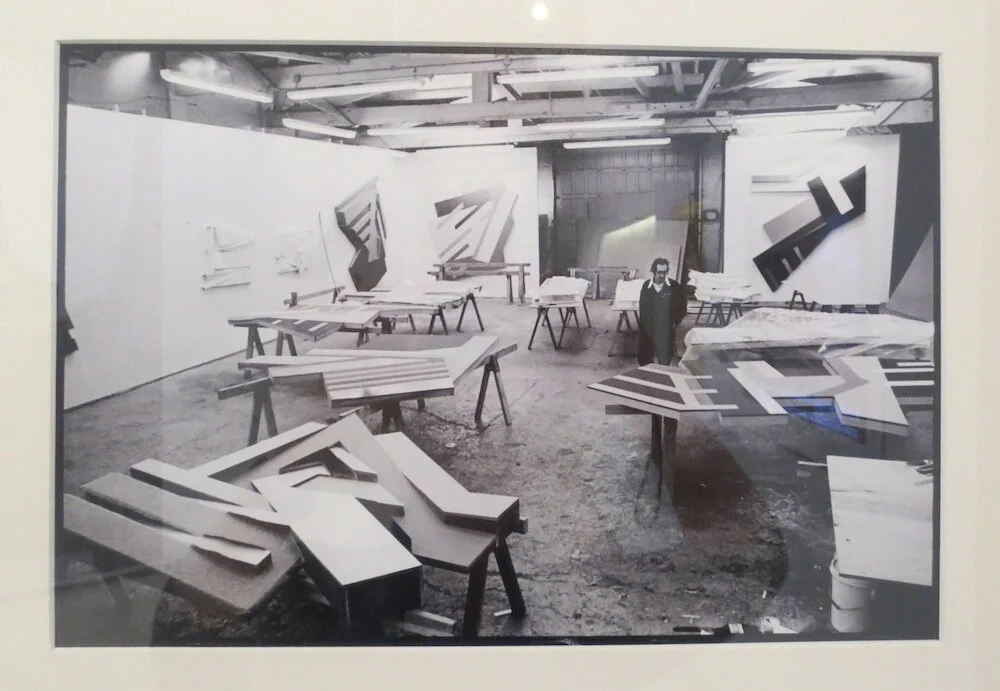

Frank Stella at his West Houston studio with works from the Polish Village series, 1974. Original photo by Nancy Crampton.

The real problem in painting has always been the same one--to make art--and so it's really a question of how you make art. Shaping the canvas was something that, I don't know, I just drifted into it. It had an appeal to me. I was never sure how much appeal it would have to anyone else. But I liked it. I liked the way it defined things and it defined the gesture of the painting in a way. Rather than having a painting full of a lot of gestures, the painting itself became a gesture. 'Make what you want to paint on' would sort of be my theme. I like to make what I'm then going to paint on.

Maquettes for Odelsk (1971-1974).

Odelsk I (1971), by Frank Stella. 90x132 in.

Odelsk I (1971)--sideview--by Frank Stella.

Bogoria V (1974/1982), by Frank Stella. 88.5x110.5x4.75 in.

Bogoria V (side view detail) , 1974/1982, by Frank Stella.

Bogoria IV (1971), by Frank Stella. 90x110x5 in.

Olkienniki III (1972), by Frank Stella. 95x84 in.

Inspiration can come from anywhere. All we have to do is pay attention to what intrigues us, moves us, captures our imagination.

[If you happen to be in Warsaw, the exhibit continues until June 20. And the Polin Museum itself is extraordinary, using the latest technology to provide a multi-sensorial experience for visitors.]

Questions and Comments:

What inspires you as an artist?

How has what inspires you affected your work, even changed your artistic orientation?

*Note: To view the conversation that was started on the former Weebly site of this blog and add your comment, click here or to start a new conversation, click "Comment" below.