Taking in Art in Poland

The opening of the 15th International Trienniale of Tapestryon May 9th was one reason I recently visited Poland, for the event takes place in my father's city, Łódź. I first heard about it in 2013, but couldn't attend then. Though I had been in Łódź in the late 1990s, at that time I knew nothing about such happenings, for I had not yet gotten immersed in textile art. In fact, I didn't even know the history of the city. Imagine my surprise when I learned that it was the center of a thriving textile industry in the 19th century. Called the Polish "Manchester," Łódź supplied goods for the Russian Empire, which spanned from East-Central Europe all the way to Alaska.

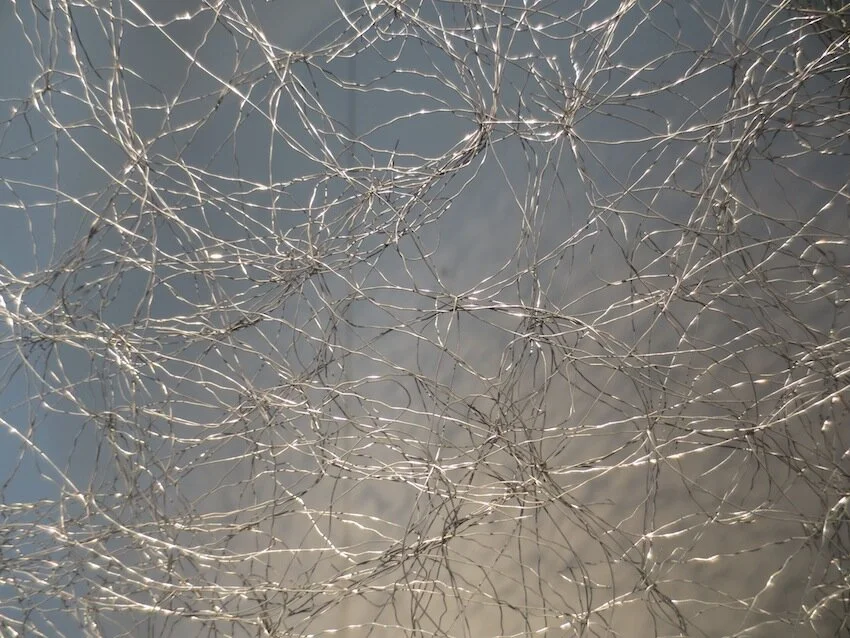

"Beautiful Waiting" (2015), by Sylwia Jakubowska. International Triennale of Tapestry 2016, Biała Fabryka ("White Factory"), Lodz, Poland.

Detail of "Beautiful Waiting" by Sylwia Jakubowska.

Photo taken from one of 4 wings of the Centralne Muzeum Włókiennictwa (Central Museum of Textiles), Lodz, formerly "The White Factory," erected by the family of Ludwik Geyer in 1835–1886. Site of the International Triennale of Tapestry.

This wouldn't mean anything to me except that my father once told me something about his father, who I now realize played a small role in that huge enterprise. My grandfather could look at a piece of cloth through a loupe and discern how to create that pattern, that is, how to set up the looms to weave it. That bit of family history remained in my memory bank for ages until one day it struck me that, though I had never learned how to weave, there I was, working with textiles. I felt a need to return to Łódź and see for myself where all this had started and how it eventually became a showcase for contemporary fiber art.

Briefly, Łódź began as a small settlement on a trade route and, by the early 20th century, grew into one of the most densely populated and polluted industrial cities in the world. Weaving originally took place in dark, dismal hovels, but some mill owners built huge steam-powered factories that turned their families into dynasties on a par with, if not wealthier than, the Rockefellers.

Izrael Poznański's Palace, originally a family residence, now the Museum of the City of Łódź.

Eventually, the boom went bust due to a series of catastrophes: The Bolshevik Revolution (1917) and the Civil War in Russia (1918-1922) ended the lucrative trade with the East; The Great Depression (1930s) and the Customs war with Germany closed western markets to Polish textiles. After decades of labor exploitation, workers' protests and riots erupted.

Today, the factories and mansions are museums and galleries, with parks and gardens. For example, Izrael Poznański's Palace (see photo above), originally a family residence in the Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque style, houses the Museum of the City of Łódź. Several rooms on an upper level are dedicated to a hometown boy, the renowned classical pianist Artur Rubinstein (1877-1982). The lower level is a gallery, where I viewed an exhibit of paintings and lithographs by local abstract artist and professor Andrzej Gieraga.

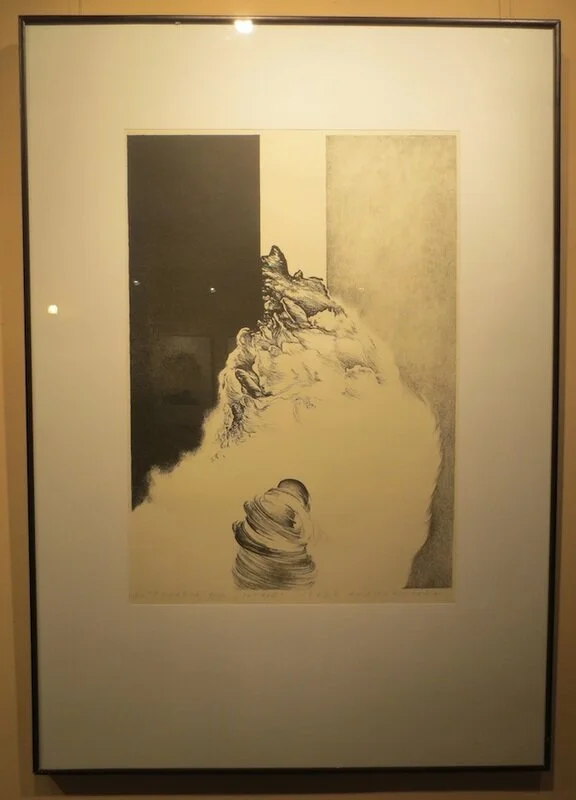

"Intruz" (1973), by Andrzej Gieraga.

"Bez Tytulu III, ok" (1973), by Andrzej Gieraga.

Walking along city streets, I also came across art on old building walls and in alley ways: The face/tree directly below and the mirrored glass in a pattern of roses underneath that are two instances.

Street art on a building in Lodz, Poland.

In this alley off Piotrokowska St. in Lodz, someone created a pattern of roses, using bits of mirrored glass to cover building walls.

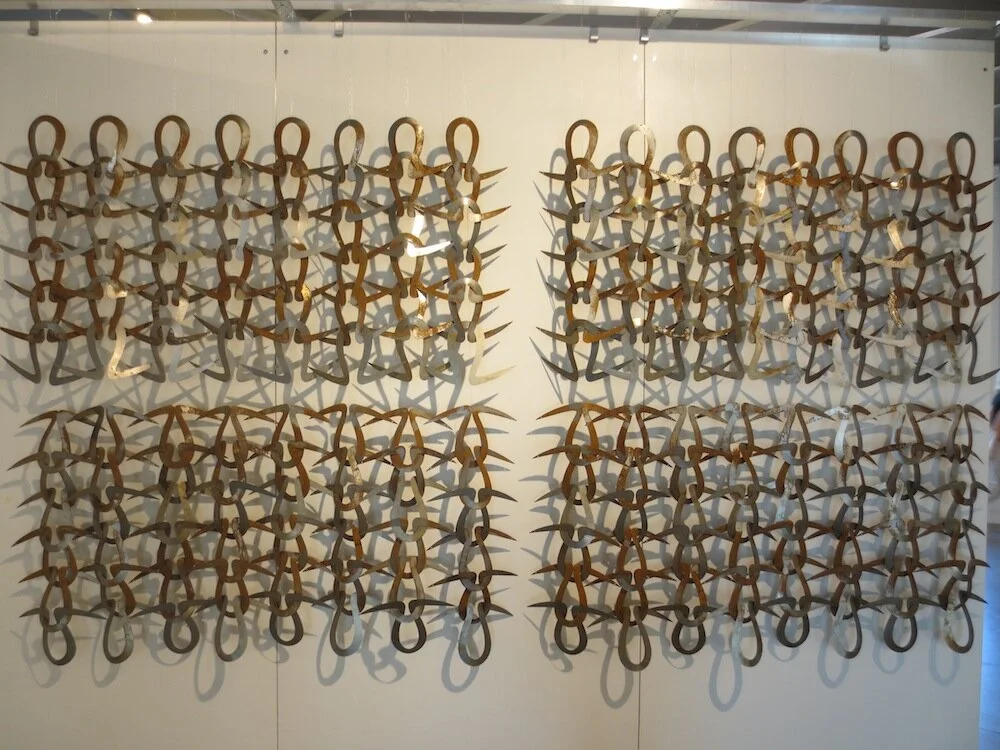

I visited the Museum of Art, located in another Poznański palace, and a cultural center where shows ancillary to the Triennale were hung. There are more than 90 such related exhibitions and events that take place across Poland as well as its borders during this year. But the most extensive exhibit is the one for which I had traveled so far, the Triennale itself. With the work of 136 artists from 46 countries displayed on 3 floors, there's no way I can include everything here. Instead, what follows is a mere sampling of the wide variety of fiber art I witnessed. It's come a long way from the cotton and wool textiles once woven for an entire empire. The definition of fiber art is stretched to include pieces that do not even consist of fiber, but may entail a relevant interlacing technique, such as the rusted metal in "Modulator" by Leonora Vekić of Croatia.

While I took photos of the entire show, it is hard to capture the feeling of being in the presence of particular pieces. Photographic images just don't have the same impact as standing in front of or walking around them. I've selected those that come across more sharply in terms of shape, color, and texture, or that are unexpected in some way.

"Modulator" (2014), by Leonora Vekić, Croatia.

Detail of "Modulator" by Leonora Vekić.

"A Dream in the Rain (En la lluvia el sueño) (2010-2013), by Sara María Terrazas., Mexico.

Detail of "A Dream in the Rain," by Sara María Terrazas

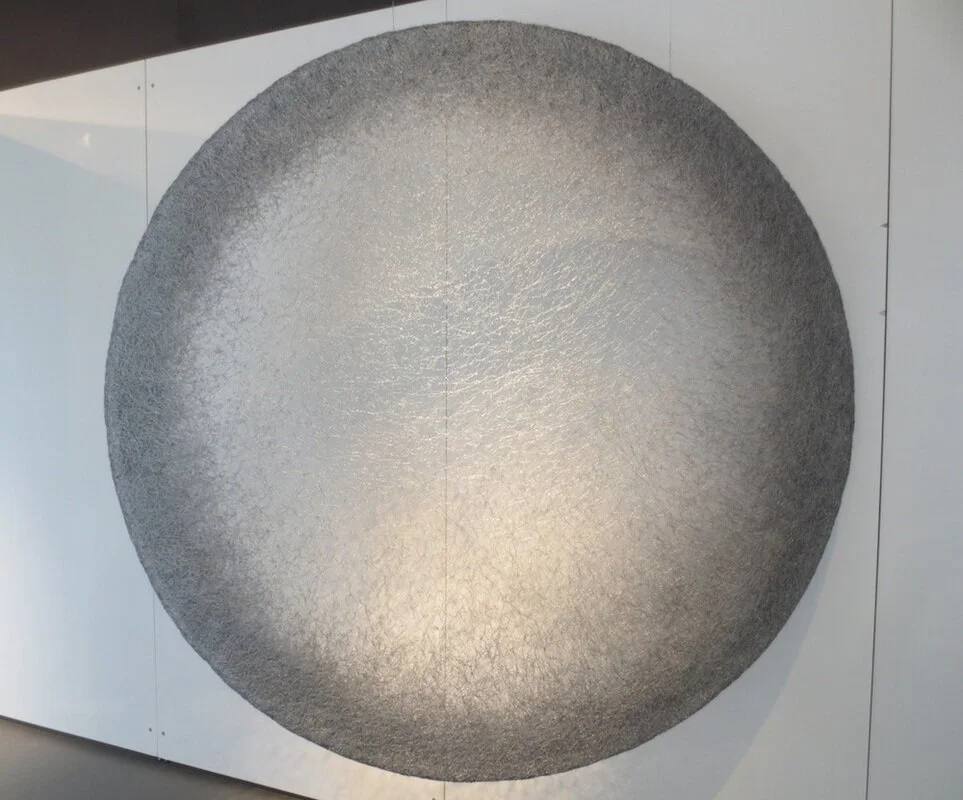

"The Round of the Wind" (2014), by Nadya Bertaux, France.

Detail of "The Round of the Wind" (2014), by Nadya Bertaux, France.

The title cards at the Triennale do not contain information about materials and methods, but in many cases, I could guess. In the two images (one full and one detail) that follow of Judith Content's work, I know that her wall pieces are hand-dyed, pieced, and quilted silk.

"Labyrinth" (2015), by Judith Content, USA.

Detail of "Labyrinth" (2015), by Judith Content, USA.

The slightest breath of air set Alina Bloch's multi-layered "Genesis" in motion, so it never looked the same from moment to moment.

Front view of "Genesis" (2015), by Alina Bloch, Poland.

Side view of "Genesis" (2015), by Alina Bloch, Poland.

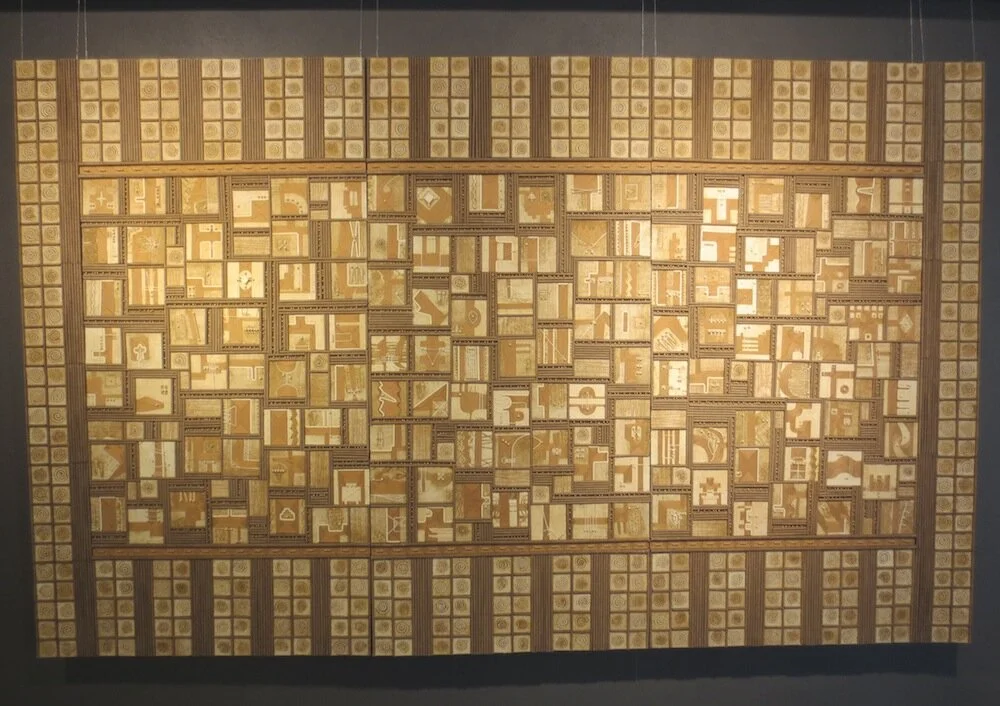

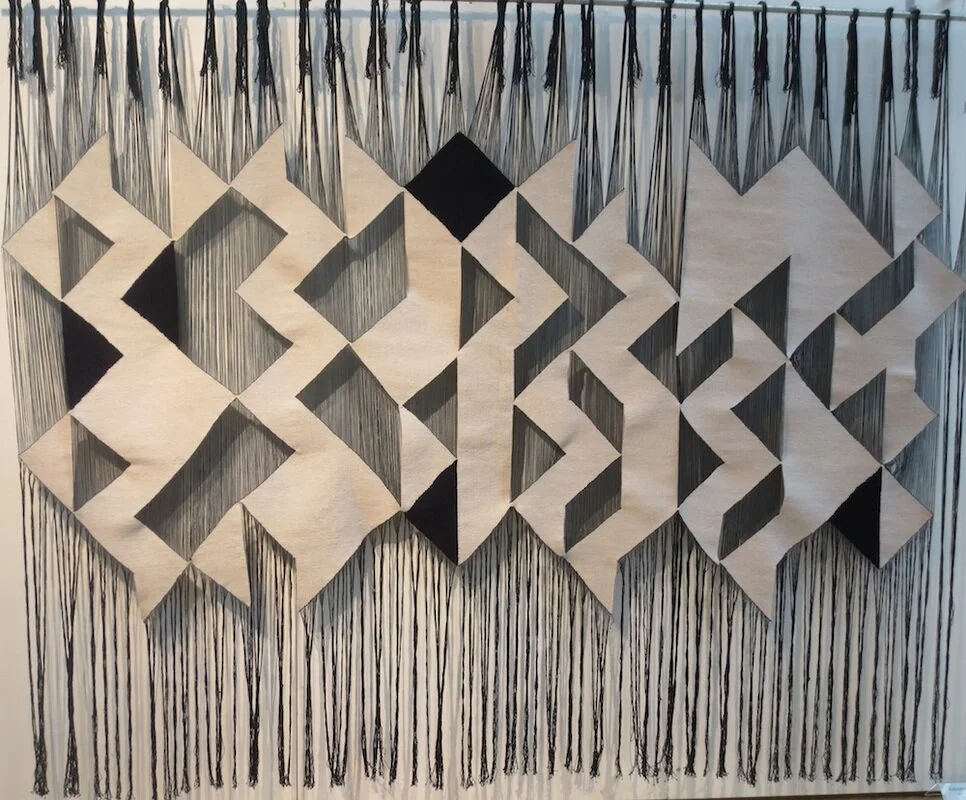

"Rhythms" (2013), by Alexandar Kulekov, Bulgaria.

Detail of "Rhythms" (2013), by Alexandar Kulekov, Bulgaria.

"Porcelain Coasts" (2015), by Rolands Krutovs, Latvia.

Detail of "Porcelain Coasts" (2015), by Rolands Krutovs, Latvia.

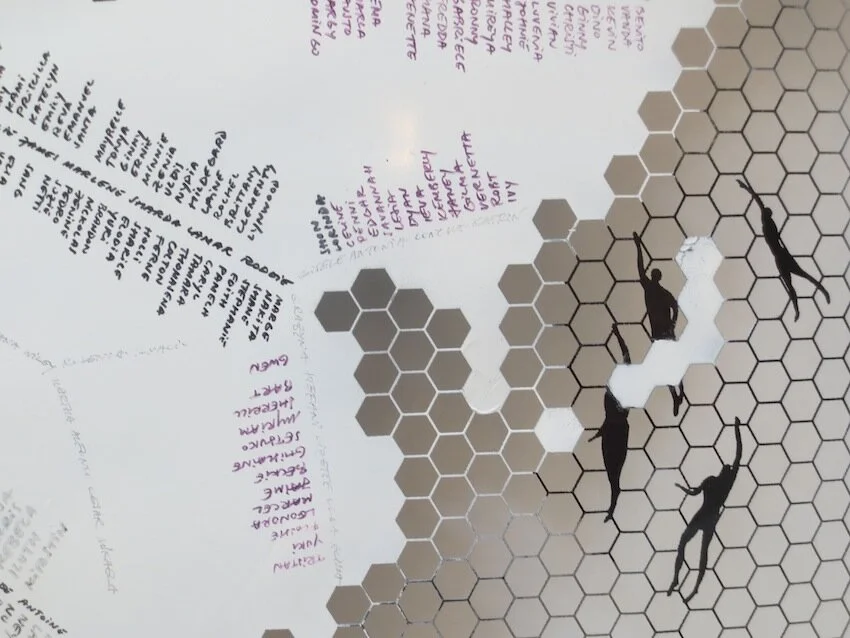

In her piece, "Mass Suicide," Androna Linartas of Mexico replicates the ancient system of quipu to convey a powerful message about the dangers of smoking. Quipus, also known as "talking knots," were devices used in the Andean cultures (South America) to collect data and keep records. A quipu usually consisted of colored, spun, and plied thread or strings made from cotton or camelid fiber. Linartas created hers with cigarette butts.

"Mass Suicide" (2011-2015), by Androna Linartas, Mexico.

Detail of "Mass Suicide" (2011-2015), by Androna Linartas, Mexico.

"Mutatis Mutandis" (2014), by Emöke, France.

Detail of "Mutatis Mutandis" (2014), by Emöke, France.

Questions and Comments:

Does your family have a particular textile history? Where did it come from?

What surprises/fascinates/interests you about fiber art today?

What traditional techniques with non-traditional materials (or vice versa) have you used in your art?

*Note: To view the conversation that was started on the former Weebly site of this blog and add your comment, click here or to start a new conversation, click "Comment" below.