Making Marks: Writing and Art

Source: https://www.craftsy.com/blog/2016/07/mark-making-ideas/

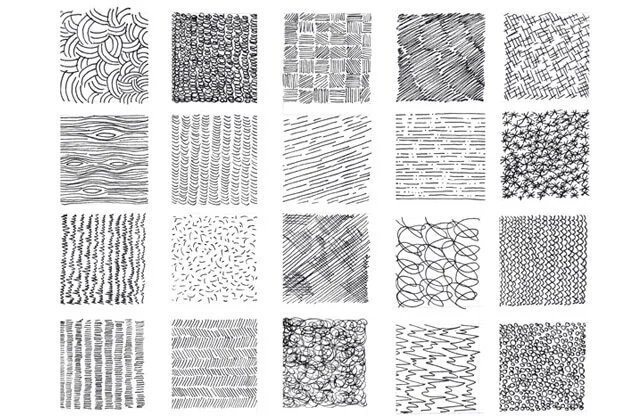

Mark making is an essential aspect of creating a work of art. We make marks with a pencil, a piece of pastel, charcoal or chalk, a brush and paint, a needle and thread, and all kinds of other instruments that let us incise lines, dots, shapes, and patterns into clay, wood, metal, stone, and plastic. The marks can be straight or squiggly, rigid or loose, singular or repetitive. They can express emotions, movement or stasis, order or chaos, weakness or strength. The range is infinite. It is with "letters" as well.

Writing is a particular form of making marks to communicate, record history, and preserve religious teachings. It is also an object of beauty in itself. That's why, ever curious, I went to the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco last Saturday to attend a program on "The Story of Writing in the Arts of Asia." I'm fascinated by the unusual and appealing marks that other people easily understand, but which I read simply as interesting lines and shapes, such as this sign in Seoul or these calligraphic versions of love in Arabic (al-hubb) and Hebrew (ah-ha-vah). To me, the elegant black lines appear to be dancing.

Al-hubb, by Larisa.lar24. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Ah-ha-vah, by Michel D'anastasio. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/maltin75/4803612829/

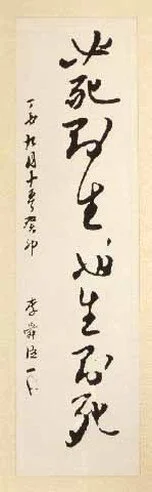

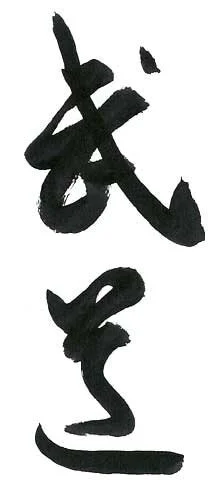

And then there's the calligraphy of China, Korea, and Japan. While the various images I include are from disparate regions and civilizations--Middle East and East Asia--I find mark making oddly unifying. Despite the barriers we encounter in language, there's something in the beauty of the strokes that connects all of us. Maybe it's because the arts have long had the power to transcend cultural differences.

"Crossing the Frozen River,"a poem in running script, undated, by the Kangxi Emperor (1654—1722). The Palace Museum, Beijing. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

E Sun-shin calligraphy. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

"Budo" shuji, brushed by Kondo Katsuyuki, Menkyo Kaiden, Daito ryu. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

I came to the tour, led by inspiring docent Julia Verzhbinsky, with some questions: Do the letters of the Hebrew alphabet have any bearing on those of Sanskrit? Do the hieroglyphs of Egypt share any commonality with the ideograms of Chinese? And where and when did writing first go beyond its practical purposes and blossom into art?

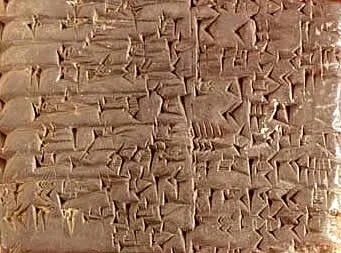

First, of course, there are those marks that were made on cave walls and rocks tens of thousands of years ago. Then, dating to around 3200 B.C.E., we have the earliest cuneiform tablets from Sumeria (between the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers) as well as small bone and ivory tablets in early hieroglyphic form from Abydos (on the Nile). Gradually, those marks morphed into others.

Ritmal-Cuneiform tablet (ca. 2400 B.C.E., Kirkor Minassian

Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Source:https://commons.wikimedia.org

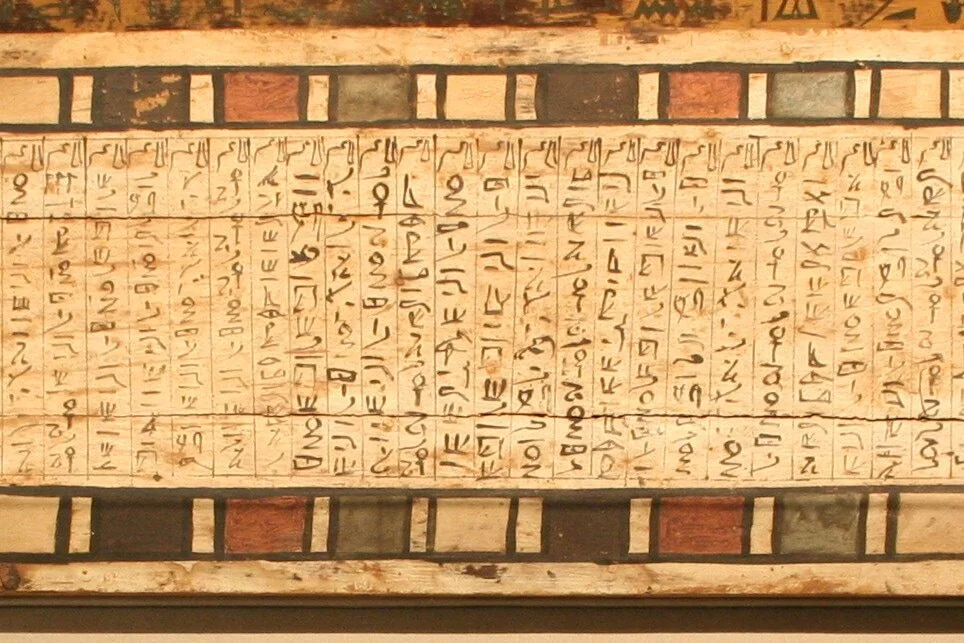

Coffin of Herishefhotep; Abusir, 9th/10th dynasty. Ägyptisches Museum, Leipzig, Germany. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Too readily, we forget that extensive travel over trade routes has existed for many thousands of years (without jets!) and that soldiers and merchants carried a lot more than arms and material goods. For example, Aramaic, which originated in Mesopotamia and is ancestral to Hebrew, Syriac, and Arabic, spread all the way to the Indus Valley under the Archaemenid Empire (4th to 6th centuries B.C.E.). I saw evidence of this on a miniature Buddhist stupa from the ancient area of Gandhara and on statues of the Buddha. Although Chinese is considered completely original, it's hard not to notice similarities between early marks in China and those made elsewhere.

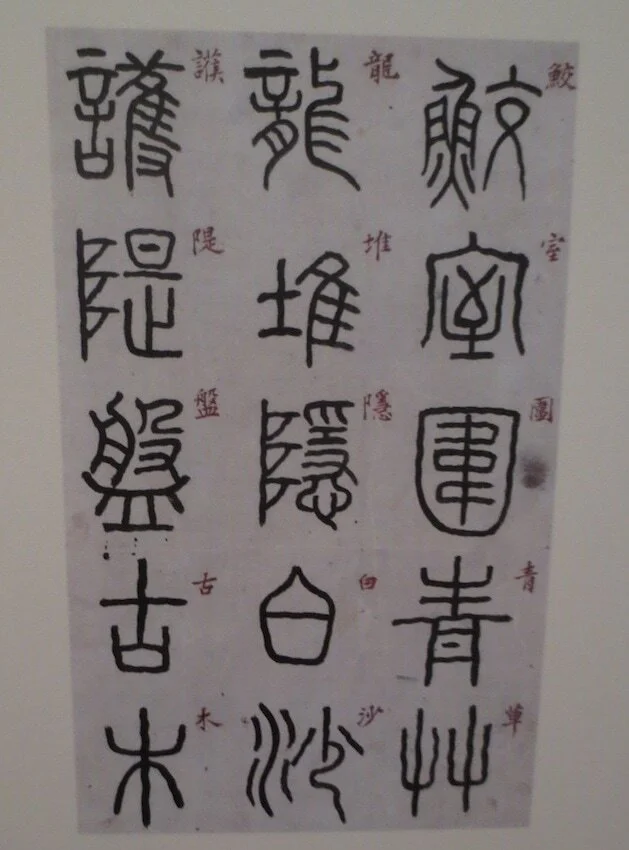

Chart of seal script, National Museum of Korea, Seoul.

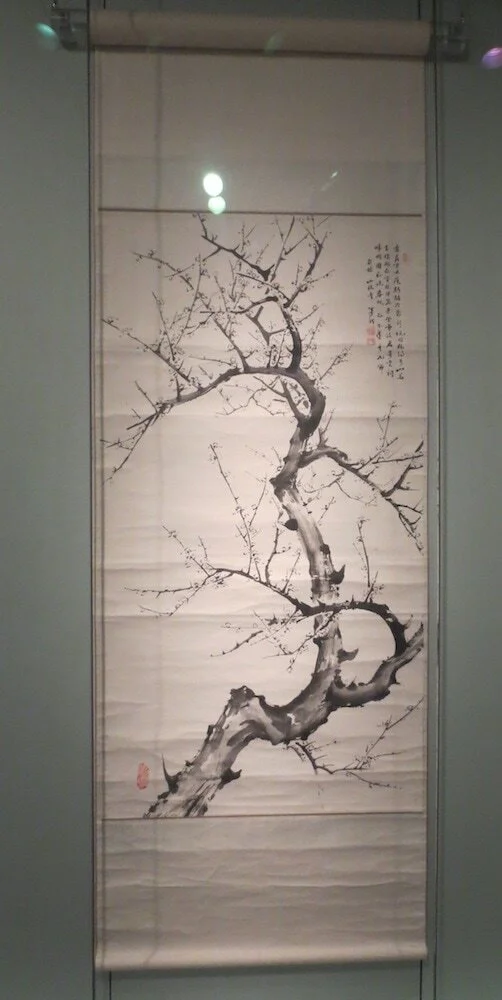

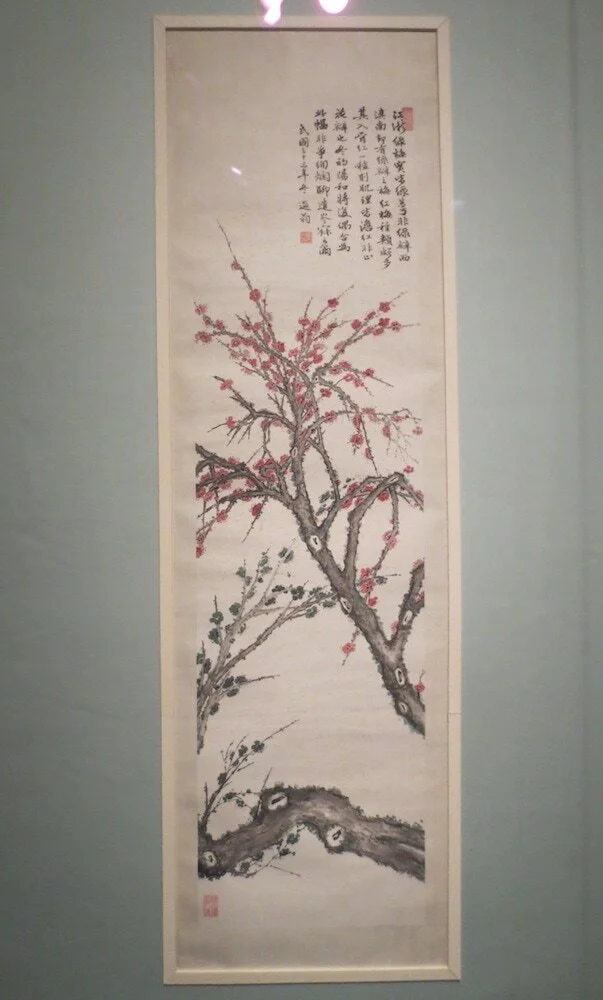

The earliest mark making in China seems to have been on oracle bones. I am drawn to the seal script that was derived from such "pictures." I can guess what they represent and find out what they mean through Google, but I appreciate them just for their interesting combination of lines. Since I'm not a calligrapher, instead I'm eager to abstract and stitch them onto fabric or paper. Although I've never been to China, I saw the marks above at The National Museum of Korea in Seoul. There I also learned about the Korean attitude toward calligraphy, which is considered one of the major arts that a true intellectual should master. Historically, to be truly adept, the calligrapher needed great knowledge about literature, history, art, and philosophy, for spiritual depth was valued along with artistic beauty. Even modern Chinese scroll paintings that I've seen, for instance, at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, bring together the three arts of painting, poetry, and calligraphy.

"Plum Blossoms" (1965), by Xiao Ru. Asian Art Museum,

San Francisco, California.

"Red and Green Plum Blossoms" (1944), by Ye Gongchuo (1881-1968). Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, California.

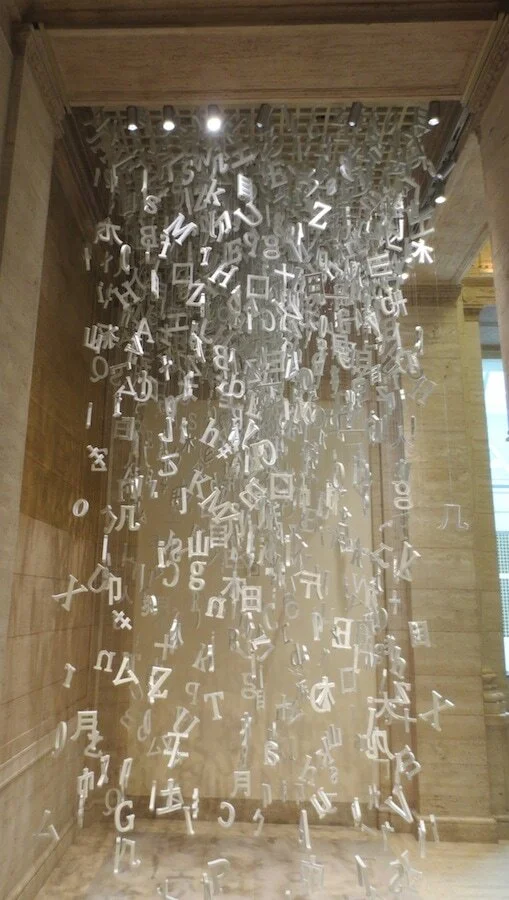

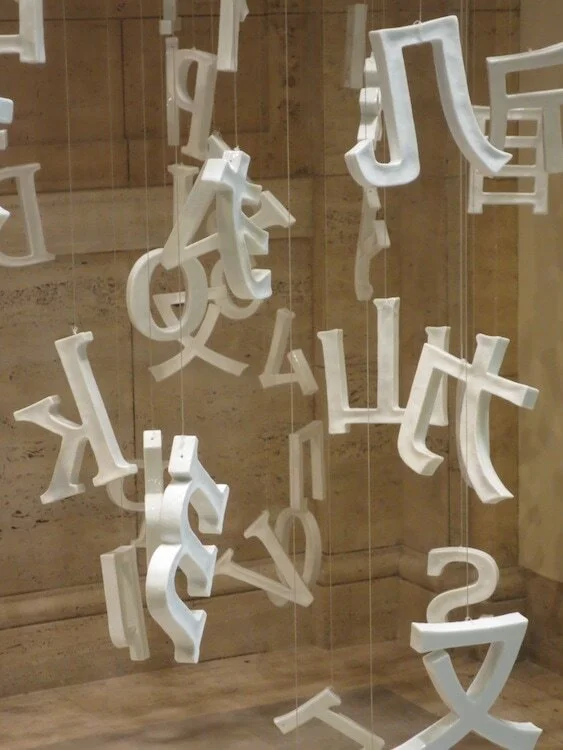

"Collected Letters" (2016), by Liu Jianhua. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, California.

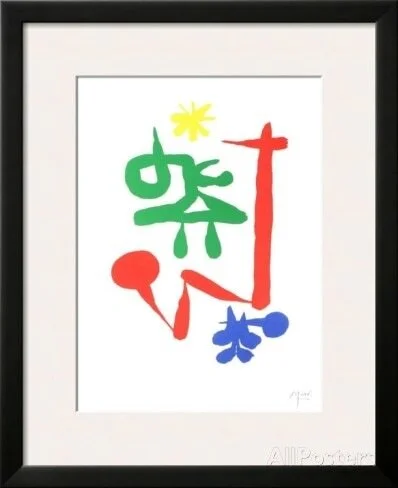

"Parler Seul" (1947), by Joan Miró. Source: http://www.

allposters.com/Posters_i10212240_.htm

For some artists today, such as Shanghai- based Liu Jianhua, a letter can be a visual unit of art in itself. He created Collected Letters (2016) by suspending cascading porcelain letters of the Latin alphabet and the radicals that form Chinese characters. Taken out of their practical role as building blocks of language, they become sculptural compositions in their own right. Liu Jianhua was inspired by the Asian Art Museum's collection of Chinese ceramics and the building's original identity as the main public library of San Francisco.

"Collected Letters" (2016), by Liu Jianhua. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, California.

Those of us involved in fiber/textile art are aware that mark making is a big topic of conversation these days. Some artists stitch in abstract marks while others add actual text and recognizable letters. Painters such as Paul Klee and Joan Miró included marks that are reminiscent of scripts from long ago in other cultures. It's ironic that the more we think we're creating something new, the more we realize that we're tapping into something very old. Ancient art, contemporary art. The East, the West. In the end, I don't see any divisions. Influences and inspirations run in both directions.

"Insula Dulcamara" (1938), by Paul Klee. Source: https://learnodo-newtonic.com/paul-klee-famous-paintings

Questions and Comments:

What kinds of marks are you drawn to in art and writing?

What do you use in your artwork: your own marks? lettering/script in your language or other languages?

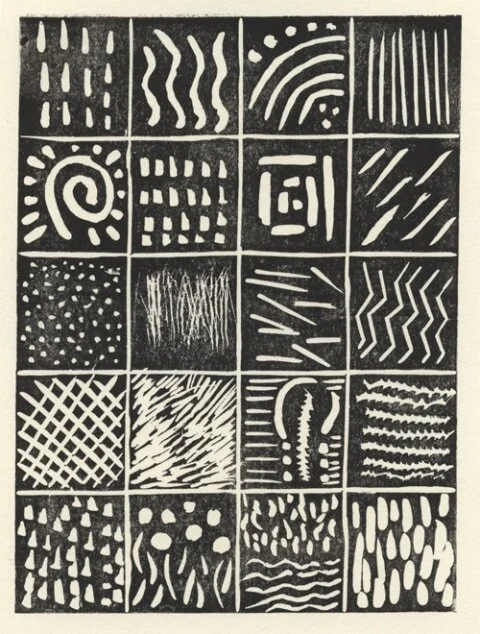

Lino cuts on polymer blocks, by digital designer and artist Charmaine Watkiss.

Source: https://charmainewatkiss.wordpress.com/2010/11/01/lovely-lino/

*Note: To view the conversation that was started on the former Weebly site of this blog and add your comment, click here or to start a new conversation, click "Comment" below.