Memories and Art

We all have memories, lasting and fleeting. Over time, new ones appear while others gradually fade away; some become more vivid or change in tone and content. And then there are those memories that aren't really our own yet haunt us, memories of episodes that occurred many decades before we were born.

The arts have been and continue to be a particularly fertile ground where all kinds of memories, pleasant and unpleasant, have seeded new work. An exhibit in San Francisco is a particularly good example of this. From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memory and Contemporary Art is on view at the Contemporary Jewish Museum (CJM) until April 2. It brings attention to the stories that were lived by others but somehow turned into the artists' stories as well.

"What Goes Without Saying" (2012), by Hank Willis Thomas. Wooden pillory and microphone.

CJM Assistant Curator Pierre-François Galpin and independent curator Lily Siegel have brought together the work of 24 artists who grapple with their past--secondhand rather than direct experiences. A widely diverse group, they question and reflect on ancestral and collective memory through sculpture, installations, fiber, photography, sound, video, and mixed media. While at least five artists focus on the Holocaust, others address the American War in Vietnam and Cambodia, the Turkish genocide of Armenians, the legacy of racial injustice in America, the Korean War, World War II in Okinawa and Greece, the Mexican Revolution, indigenous culture in Alaska, and more.

Kevlar Fighting Costumes (2015), by Nao Bustamente. An homage to the courageous women soldiers (soldaderas) who fought in the Mexico revolution (1910-20. Re-imagined traditional garments, only now with protection against bullets and knives.

The exhibit is multi-layered, appealing to our senses and emotions, provoking not only thought but also compassion. It was originally inspired by Dr. Marianne Hirsch's research on what she calls "postmemory." Because there is so much to convey about this subject and about the individual artists themselves--how such memories affect them and how they work with them through their art--I can't begin to address this all here. Nor can I include photos of everything, especially because of the mirror effect of some pieces (basically, you'd see me taking a picture!). I'll introduce a few examples and, if you're interested, you can watch vimeos, skypes, panel presentations, and other communications from the artists on the CJM website. Given the enormous number of refugees in the world since the 20th century, this is an extremely compelling issue. I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that there is a huge population suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome because of their own memories and those of generations before them.

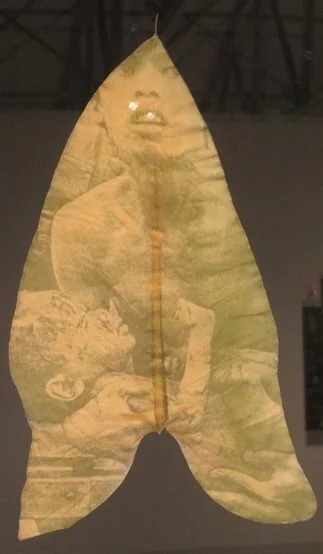

From the series "Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War,” by Binh Danh.

Artist Binh Danh, who visited Vietnam for the first time since he left as a child on a refugee boat in the 1980s, was struck by how much the landscape has remembered the trauma of war. Growing up in the U.S., he saw photos of children with missing limbs because of bombings and Agent Orange. To capture those times and effects, Binh Danh uses the natural chlorophyll process. He produces a digital transparency, places it on top of a living leaf, sandwiches that between glass and a backing board, and then exposes it to the sun. Combining technology and nature in this way is new to me, so I was especially struck by how well it represents the poignant tragedy of war in Vietnam in the fragility of a leaf. As the leaves die, so will the pictures, though memories linger.

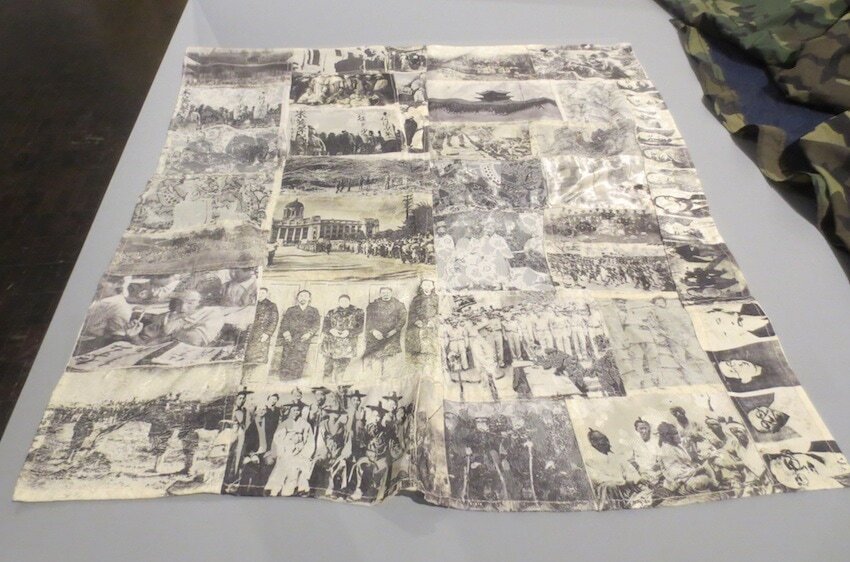

"Mother Load" (1996), by Yong Soon Min.

Yong Soon Min, born as the Korean War ended, immigrated to California when she was seven years old. She uses the Korean tradition of bojagi (patchwork) to create her installation representing different eras. She sewed together black and white photographs from the Japanese colonial period that she printed on fabric. She also stitched together color photographs to make a carrying cloth for a bundle. In addition, there is camouflage fabric representing the Korean War, her mother's red scarf, hanbok (traditional women's costume), and shoes. The artist cut some of these items in half to indicate that a part of oneself gets left behind in the native country while the other starts a new life elsewhere. "Mother Load" is about bearing the load of memories her mother transmitted.

"Mother Load" (1996), by Yong Soon Min.

If you've read the book or seen the movie, "The Garden of the Finzi-Continis," you'll recognize the name Eric Finzi and the objects in his aluminum and glass sculpture. He is a descendant of a family that witnessed the fascist takeover of Italy and that was deported to concentration camps in Germany. Strong memories related through stories told to us by others can become internalized and deeply entangled with our identity and place in the world. As Finzi says, "A story and family memory can assume as much importance as anything that has happened to you. The collective memory can be incredibly powerful." Perhaps this is so because memory is not necessarily voluntary nor dependent on historical facts, but can be a conglomeration of feelings and sensations.

"Tennicycle" (2014), by Eric Finzi.

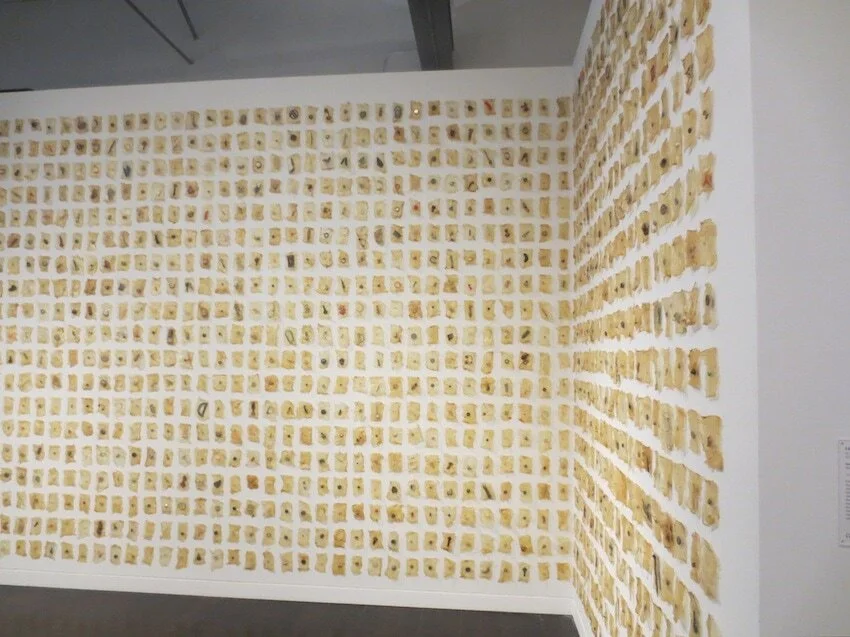

Loli Kantor, a photographer based in Fort Worth, Texas, was born in France and grew up in a Holocaust survivor community in Israel. Bernice Eisenstein, a mixed-media artist based in Toronto, also was raised among survivors. On the other hand, Lisa Kokin is not a child of survivors, yet watching film footage of Holocaust victims as a child in Long Island, New York, traumatized her as though she, too, could experience the horrors. She has spent a great deal of her artistic career confronting the fears that were embedded by what people she never knew had endured. "Inventory," her mixed-media gut installation on two walls, is composed of more than 1,000 scraps of cloth and paper, earrings, buttons, and other small found items that comprise the lives of such individuals. Kokin created it after visiting the Buchenwald concentration camp, where she saw piles of humble objects left behind by those who were killed. She says that her artwork is a way to process information. Though it doesn't entirely eradicate the terror, it does help. She believes it's her responsibility as an artist to address past events of import so that future generations can place them in an appropriate context. All of these artists are using their work to oppose the unfortunate tendency toward cultural amnesia.

"Inventory" (1997), by Lisa Kokin.

Detail of "Inventory" (1997), by Lisa Kokin.

Although raised on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, Silvina Der-Meguerditchian had four grandparents who were Armenian refugees. When her uncle approached her with her grandmother's suitcase and said he'd throw it out if she didn't take it, she found a treasure trove of documents and photographs. She knew this was her connection to the many people who were part of her heritage, people spread far out from their homeland. She decided to knit them all together by crocheting the photographs with wool to create the "carpets" she calls "Family I and Family II." They're a reconstruction of something old and something new, a way to recover a sense of belonging that she felt had been taken away from her.

"Family I and Family II," by Silvina Der-Meguerditchian.

Detail of "Family I and Family II," by Silvina Der-Meguerditchian.

My final images are of a rug cooperatively woven of 2,000 silk ties in the village of Kalavryta, Greece. Foutini Gouseti, born in Athens but now based in Rotterdam, heard a story from an old man who was only a boy during World War II. In 1943, the entire male population over the age of 14 was executed and the town destroyed by the Nazis. Only women and children survived in ruins, partly through international relief efforts. The boy was sent to pick up and bring home what was designated for them. When his mother opened the big package, rather than badly needed food and clothing, she found 2,000 silk ties. For the boy, this was a happy memory because of the many bright colors during such a dark time. For the mother, it was not the hoped-for relief. Not knowing what else to do with the ties, she wove a traditional kourelou carpet. The old man remembers that they were starving and freezing, but they could walk and sit on silk. Gouseti's Kalavryta 2012 is a contemporary recreation of the one that was made from the strange gift of ties.

"Kalavryta 2012," by Fotini Gouseti.

Detail of "Kalavryta 2012," by Fotini Gouseti.

While the exhibit title refers to a phrase found in word and song in Jewish practice: l’dor vador—the call to pass tradition from one generation to another--the exhibit itself embraces many historical events of different cultures. Who could have anticipated that this phrase would eventually take the form of passing on memories from generations that actually experienced dreadful events?

Questions and Comments:

What memories have you inherited about experiences that are not your own? Have you incorporated them in your artwork and, if so, how?

French writer Marcel Proust (1871-1922) is famous for pointing out how our senses trigger memories. Dipping a madeleine into a cup of tea--the smells wafting into his nostrils--unleashed a flood of memories that became his 7-part novel, À la recherche du temps perdu(Remembrance of Things Past). Has something similar happened to you? Did you turn those memories into some form of art?

*Note: To view the conversation that was started on the former Weebly site of this blog and add your comment, click here or to start a new conversation, click "Comment" below.