Art: A Tool for Social Change?

Roman collared slaves in a marble frieze from Smyrna (Izmir, Turkey), 200 C.E. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

“No people, in all of human history, have ever been liberated by the creation of art. None,” says Henry Louis Gates, Jr., an American literary critic, historian, filmmaker, and professor who also directs the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. Taken at face value, that statement might dampen my spirits as an artist. But in examining Gates’s premise, I imagine he means that a work of art can’t literally free a slave or political prisoner. On the other hand, art can definitely inspire people to act, to do something about slavery, to campaign for the release of someone unjustly imprisoned, to protest against war. Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937) is a perfect example.

Tiled version of Picasso's famous painting “Guernica” in the Basque town of Guernica, Spain. Photo by Tony Hisgett. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

“Guernica” was Picasso’s immediate reaction to the Nazis’ devastating bombing practice on the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. In depicting the tragedies of war—the suffering inflicted especially on innocent civilians—the painting became an anti-war symbol that continues to serve as an admonition by reminding us of these horrors. A brief tour of the painting helped to bring the war to the world’s attention. It also had a significant impact on Faith Ringgold (b. 1930).

Ringgold, an American painter, writer, mixed media sculptor, activist, quilter, and performance artist, used to visit New York’s Museum of Modern Art to look at Guernica, where it had its own room. She decided long ago that she wanted to make a difference and would use art to do so. Her work reflects her political activism and personal story within the context of the women’s movement.

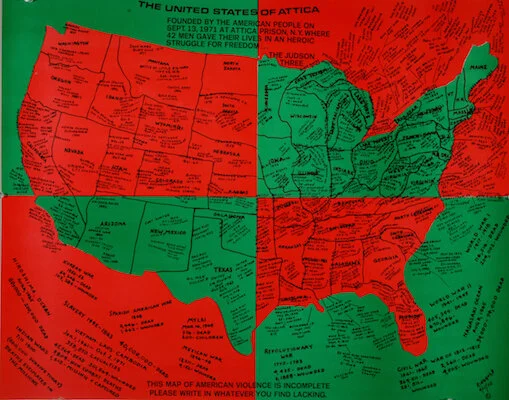

“The United States of Attica” (1971-72), by Faith Ringgold. Source: acagalleries.com/faith-ringgold-the-70s/

Resolute in her belief that “artists have the job of documenting their times,” through her art Ringgold grappled with the social and political issues of the 1960s and 1970s, including race, identity, and violence. Creating political posters, she intended to makes these problems not only visually prominent but also to encourage awareness and dialogue toward solving them. In “The United States of Attica” (1971–2), Ringgold presents a map that cites the location of numerous riots, murders, and wars, thus chronicling casualties of hate and violence.

“The Sunflowers Quilting Bee at Arles” (1991), by Faith Ringgold. Source: sites.google.com/a/odu.edu/teaching-learning-in-2015/

Ringgold also re-interprets the traditional function of quilt making, using quilts not for beds but for narratives about her life and those of others in the black community. In "The Sunflowers Quilting Bee at Arles," prominent black women (e.g., Mary McLeod Bethune, Sojourner Truth, and Rosa Parks) are stitching a sunflower-patterned quilt in a sunflower-filled field where van Gogh looks on. In bright colors, she highlights female solidarity as well as individual and group struggle in black history.

Did Ringgold’s artistic output result in direct liberation? As Gates believes, probably not. However, in her efforts to be a power for positive change, she has been a tremendous role model who has inspired and influenced many artists and non-artists alike. Why? Because artists generally sit in the vanguard of social and political movements. They employ stories to open the eyes of viewers and reflect upon their relationships to the world around them. For Ringgold, the concern is about racism and violence. For other artists, it’s about our environment—species going extinct, climatic extremes, polluted waterways. They ask whether art can play a role in sustaining the earth. Some of them have answered with projects to restore blighted landscapes.

“Wheatfield—a Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan” (1982), by Agnes Denes. Source: observer.com on widewalls.ch/environmental-artists.

Hungarian-born conceptual artist Agnes Denes (b. 1938) is often called “the grandmother” of the early environmental art movements. Her interest is in our perception of natural cycles and stewardship. She spent six months creating her most famous artwork “Wheatfield” (1982), which included cultivating a field of golden wheat on two acres of landfill covered with rubble near Manhattan’s Wall Street.

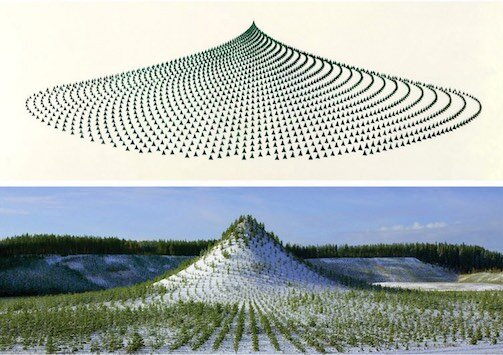

“Tree Mountain” (1992-96), by Agnes Denes. Source: kottke.org/tag/Agnes%20Denes. Website also includes a brief video.

Another nature-reclamation art project by Denes is “Tree Mountain,” a human-made mountain in Finland that is 125 feet high and covered in 11,000 trees that were planted in a Golden Ratio configuration. Her four-year project of bioremediation was intended to restore the land that had been destroyed by mining activity. The virgin forest protects against erosion, increases oxygen production, and provides a home for wildlife. It took 11,000 planters to initiate an ecosystem that will take 400 years to fully develop.

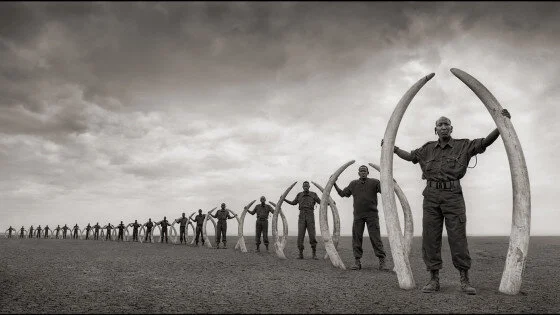

Line of Rangers Holding Tusks Killed at the Hands of Man, Amboseli National Park, Kenya (2011), archival pigment print by Nick Brandt. Source: artworksforchange.org/portfolio/extinction/

According to their website, Art Works for Change “strives to harness the transformative power of art to promote awareness, provoke dialogue, and inspire action…to address…human rights, social justice, gender equity, environmental stewardship and sustainability…creating experiences that are at once emotional, intellectual, and sensory…as a crucible where artists, museums, advocacy organizations, and local community may unite as a collective force for change.” For example, the exhibition “Ethics, Excess, Extinction” explores the reality of endangered wildlife, as well as a vision of a world in which animals are respected and protected from suffering and commercial exploitation. Participating artists include Nick Brandt, Antonio Briceño, Rohan Chhabra, Ryder Cooley, Billie Lynn Grace, Gale Hart, Andrea Hasler, Chris Jordan, Kahn & Selesnick, Karen Knorr, Kiki Smith, Karolina Sobecka, and Esther Traugot.

“Cigarette Butts” (2013), part of “Running the Numbers: An American Self-Portrait (2006 - Current),” by Chris Jordan. Source: chrisjordan.com/gallery/rtn/#cig-butts/.

Here’s what one of those artists does in his art practice. The image above looks like a quiet forest somewhere in the Northwest. But in a close-up image below, Seattle-based environmental artist Chris Jordan (who used to be a lawyer) is making a statement about environmental and individual health. The forest picture is comprised of 139,000 cigarette butts, equal to the number of cigarettes that are smoked and discarded every 15 seconds in the U.S. They represent the number one littered item found in America’s public spaces (parks, beaches, waterways, urban environments). Because the butts leach numerous toxic chemicals and carcinogens, they have such far-reaching effects on the environment as contaminating water sources and poisoning wildlife. And the filters don’t biodegrade because they are made of a plastic called cellulose acetate.

Close-up of “Cigarette Butts” (2013), part of “Running the Numbers: An American Self-Portrait (2006 - Current),” by Chris Jordan. Source: chrisjordan.com/gallery/rtn/#cig-butts/.

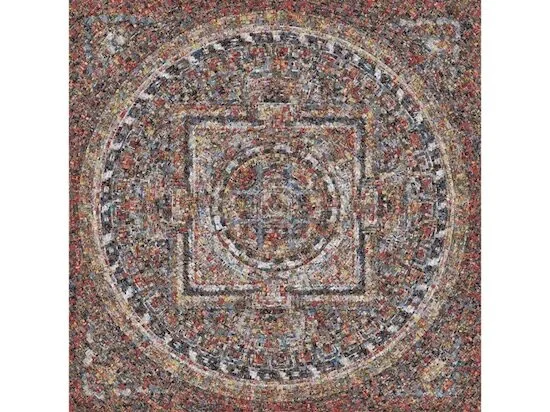

“Three Second Meditation” (2011), by Chris Jordan. Source: chrisjordan.com/gallery/rtn/#meditation/.

In “Three Second Meditation” (2011), Jordan uses the traditional Tibetan art of making a mandala to convey another message. The image depicts 9,960 mail order catalogs, equal to the average number of pieces of junk mail that are printed, shipped, delivered, and disposed of in the U.S. every three seconds—consumerist culture in extremis. It’s another example of Jordan’s efforts to translate enormous statistics that don’t seem to touch us into a visual language that we can feel, so they’ll matter to us. He’s not assigning blame, only suggesting that we face the question of how do we change as a culture collectively and individually? You can watch his 2008 TED talk here. And you can watch a film he made here.

Close-up of “Three Second Meditation” (2011), by Chris Jordan. Source: chrisjordan.com/gallery/rtn/#meditation/.

There’s no question that I could add so many more names and images—including Judy Chicago, Nina Simone, and contemporary work about the #metoo movement—but I’ll end with a few comments. If this topic interests you, there is more to read in an earlier post (2/14/16) exploringtheheartofit.weebly.com/blog/responding-artistically-to-our-times.

If we consider art a form of communication, then artists express what’s important to them, and there’s no judgment about what they choose to focus on. Some want to depict Nature’s beauty or their own dreamscapes; others want to convey a political stance or economic inequity. Whatever it is, aren’t we hoping to change minds and hearts in some way? Maybe challenge assumptions, spark new ideas, and create a different vision for the future? A gorgeously rendered landscape could lead us to pause and appreciatively take in our surroundings while out walking. A sympathetically painted or photographed portrait could transform how we look at an old woman or a homeless man or a person of color or culture different from our own.

Pearl Primus in Folk Dance (1945). Photo by Gerda Peterich. Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival Archives. Source: danceheritage.org/primus.html

While art itself will not directly solve such deeply-rooted problems as racism, homophobia, misogyny, or anti-Semitism, it can play an informative role, one that animates discussion and engagement by interpreting abstract concepts as something concrete that we can see, touch, and hear. Nor can art free people from the tyranny of their despotic government, but it can generate worldwide solidarity for their struggle. As Pearl Primus, (1919-1994), American dancer, choreographer and anthropologist, said of her artistic exposition of Strange Fruit on the trauma of lynching: This dance is truly a social weapon. Its results are not immediate, for education is a slow process, but it contributes something.

Questions and Comments

Do you have a specific message you want to communicate through your art? How do you go about it?

How does other artists’ work that addresses social and political issues affect you? Does it influence how you feel and think about them? What art has changed your mind and heart?

Do you find yourself more likely to remember something through a story or an image than through the facts you read in a textbook? If so, why do you think that’s so?