Art in the Diaspora

Diaspora is a word that comes up a lot in the news, especially in regard to refugee disasters. It signifies a population scattered from its homeland. It especially defines forced mass migration, often due to political, ethnic, and religious persecution and/or severe social and economic conditions. Because dispersion is worldwide, it’s perhaps not surprising that the phenomenon has led to what we call “Diaspora Art.”

Diaspora art is created by artists who have moved from their geographic origin to another place (or whose families have) and express their diverse experiences as immigrants. Coming into contact with cultures, societies, philosophies, arts, and technologies different from their own heritage leads to a range of articulations in their art. Diaspora artists investigate their complex sense of identity resulting from trauma and displacement, challenge the established art world, offer alternative narratives, protest conditions inflicted on their group, and influence how we think about multicultural living.

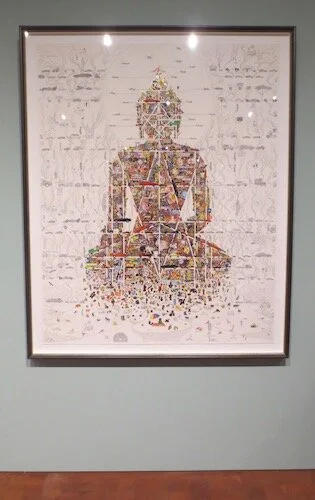

Two mixed media pieces by Tenzing Rigdol flank a traditional seated Buddha. “The White Proposal” on the left; “Wrathful Dance” on the right.

People are constantly relocating from every continent across the globe. But that doesn’t always result in diaspora art. I arrived in the U.S. from Europe with my parents when I was a young child. However, I can’t say that I create diaspora art, either as a writer or fiber artist. However, others certainly do. Recently, I witnessed the impact of the worldwide phenomenon of migration on the art of a particular community.

At the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) until May 26, the exhibit “Boundless: Contemporary Tibetan Art at Home and Abroad” features work by internationally renowned Tibetan artists side by side with rare historical pieces. This juxtaposition enables viewers to perceive how the past inspires modern representations and how the present transforms ancient traditions. Applicable to this exhibit is the term “hybrid aesthetics," which describes the combining of different art cultures, styles, or techniques to create something uniquely contemporary. The artists in the exhibit are based in the East and the West: Lhasa, Tibet; Dharamsala, India; Kathmandu, Nepal; New York; and the San Francisco Bay Area, which has the fourth-largest Tibetan community in North America. Their work varies from painting and sculpture to multimedia, performances on video, and collage.

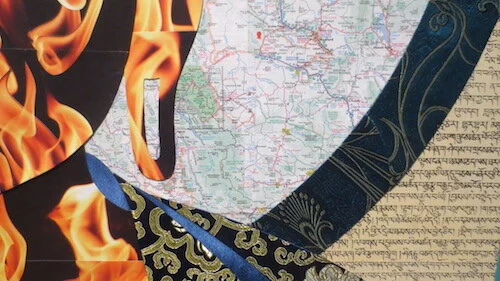

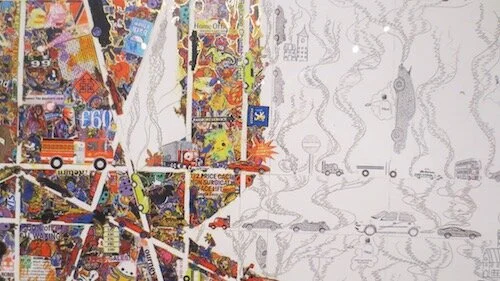

Detail of “Wrathful Dance” (2014), by Tenzing Rigdol. Mixed media on canvas.

Artist, poet, and activist Tenzing Rigdol was born in Nepal in 1982. He employs the silhouette of the Buddha to highlight issues Tibetans are dealing with today. In both mixed media pieces, he used silk appliqué and collage to reflect the complicated threads that weave together Tibetan communities in the diaspora. In “Wrathful Dance,” the mandorla around the Buddha’s head is a map of the Denver, Colorado area, where the artist immigrated and earned a degree in studio art. Woodblock-printed Tibetan texts make up the background behind the textile halo and robe. These written prayers also hark back to the artist’s paternal family, who once produced ink for printing scriptures. In the detail image above, the dramatic flames reference self-immolation protests made in an effort to bring international attention to the plight of Tibetans living under Chinese rule. In the image below, in addition to Tibetan text, there is Chinese text, a white-paper proposal for self-governance, which the Tibetan Government in Exile prepared for the Chinese government to consider.

“The White Proposal” (c.2014), by Tenzing Rigdol. Mixed media on canvas.

The artwork in “Boundless” made me realize how much change has transpired since I sojourned in the Tibetan refugee community of Dharamsala during my first visit to India in 1981-82 . For more than a thousand years, Tibetan artists/artisans made paintings, murals, statues, and buildings in service to the practice of Tibetan Buddhism, not unlike what has taken place elsewhere, such as in ancient and medieval Europe. Sacred art has as its intention the spiritual uplifting or awakening of devotees, whereas contemporary art is generally secular. While thangkas (scroll paintings), sand mandalas, and other items are still created, after exposure to different styles, techniques, and materials, contemporary Tibetan artists do not necessarily follow a long-established protocol or patently religious purpose.

“Milarepa” (18th c., Tibet). Opaque pigments and gold on textile. This portrait was the first of what was once a set of 19 thangkas. The composition relates a Buddhist teaching lineage as well as the first important scenes from the life of Milarepa life (1052-1135), one of Tibet’s most famous yogi/saints and poets.

Detail of “Milarepa” thangka.

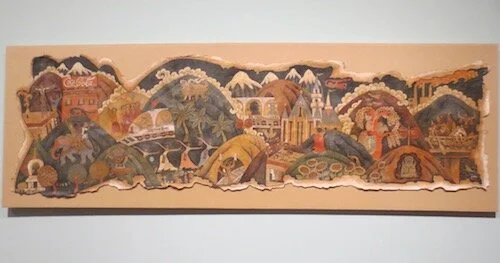

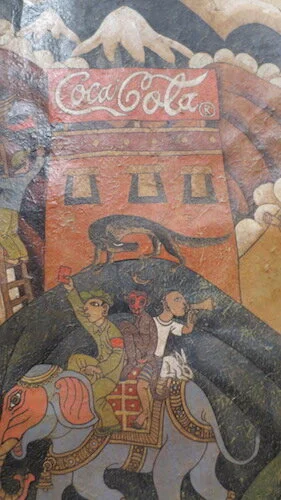

The artist Gade, born in Tibet in 1971, painted “Lhasa Train” in response to the opening of the Lhasa-Qinghai railway in 2006, a major event with far-reaching repercussions. The images capture a jarring mixture of cultures and belief systems. Gade has said, “My generation has grown up with thangka painting, martial arts, Hollywood movies, Mickey Mouse, Charlie Chaplin, rock ‘n’ roll, and McDonalds. We still don’t know where the spiritual homeland is—New York, Beijing, or Lhasa. We wear jeans and T-shirts and when we drink a Budweiser, it is only occasionally that we talk about ‘Buddhahood’.”

“Lhasa Train” (2006), by Gade. Acrylic and mineral pigments on handmade paper mounted on canvas.

Detail of “Lhasa Train” (2006), by Gade.

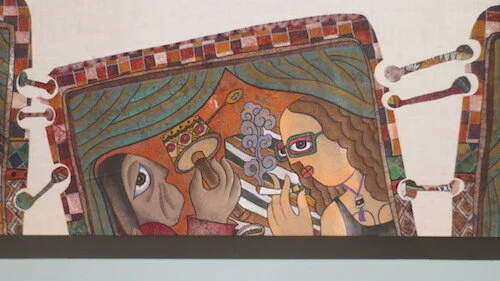

Dedron is another artist hailing from Tibet (b. 1976) who addresses the arrival of the Lhasa-Qinghai train. In her image, she reflects the odd coming together that is taking place: a Euro-American tourist is smoking in the face of an older Tibetan woman pilgrim lifting her prayer wheel. Tibetan goods (carpets, Buddhist figurines) and Tibetan mastiffs fill another car. At one end of the canvas, there are wispy mists around the serene Tibetan plateau while, at the other end, gray smog envelops a Chinese city. According to the title card, Dedron is a self-taught artist who has instructed blind children in the visual arts at a local school. Both her piece and that by Gade are in the shape of traditional scriptures, which are held by carved wooden covers (see below her work) .

“Train” (2006), by Dedron. Mineral pigment on handmade paper.

Detail of “Train” (2006), by Dedron.

Wooden scripture cover (c. 15th c., Tibet). Wood and mineral pigments.

Born in Lhasa in 1961, Gonkar Gyatso immigrated first to Dharamsala, then to London and New York, and now lives in Chengdu, China. His work “Buddha in Our Times” alludes to themes of non-duality and non-differentiation. In it, a proliferation of Chinese, American, and European logos merge into the shape of a Buddha. Buildings and vehicles spewing noxious emissions enter and exit the Buddha along roads that cross each other. They imitate the lines and measurements used by traditional Tibetan Buddhist thangka painters to ensure that the icon’s proportions are accurate. According to Gyatso, the Buddhist form accepts, without discrimination, all positive and negative aspects of society.

“Buddha in Our Times” (2010), by Gonkar Gyatso. Screen print, gold and silver leaf on paper.

Detail of “Buddha in Our Times” (2010), by Gonkar Gyatso.

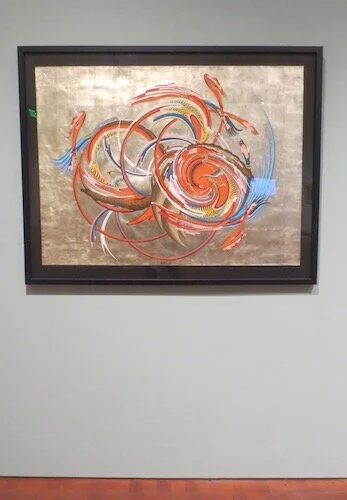

Trained as a traditional thangka painter by his renowned father Urgen Dorje, Tsherin Sherpa began experimenting with contemporary forms after his arrival in San Francisco in 1998. He was born in Nepal in 1968. In “Red Protector,” he digitally altered a traditional image of a protector deity, then painted the resulting form onto a larger canvas, combining traditional (gold leaf) and nontraditional (acrylic paint) materials.

“Red Protector” (2015), by Tsherin Sherpa. Gold leaf, acrylic and ink on linen.

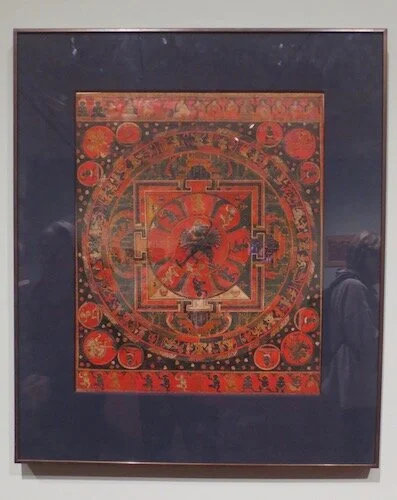

The mandala below is an ancient representation, giving a sense of where the whirling in Dorje’s painting might have come from.

“Hevajra Mandala” (14th c., Tibet). Opaque pigments and gold on textile. The central blue figure, Hevajra, a meditational deity of Anuttarayoga Buddhist Tantra, has 8 faces and 16 hands holding skull cups. Holding a curved knife and skull cup, his consort, Vajra Nairatmya (Selfless One) embraces him.

Detail of “Hevajra Mandala” (14th c., Tibet).

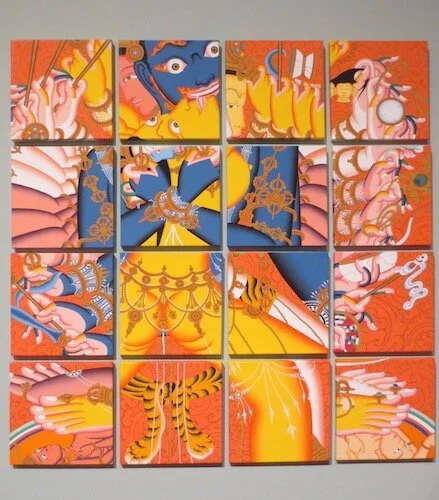

Tsherin Sherpa also created “Kalacakra,” a 16-panel work in which he explores issues of illusion and perception. He dissected the image to provide an opportunity for viewers to complete it in their own minds. He uses the traditional form of the father-mother (yab-yum) union that represents wisdom and compassion, both of which are necessary to attain enlightenment. Despite the nearby sculpture of Cakrasamvara with Vajravarahi (see below Sherpa’s painting), it is difficult to bridge the gaps in canvas, suggesting that we question our perceived assumptions about the world around us.

“Kalacakra” [“wheel(s) of time”] (no date), by Tsherin Sherpa. Mineral pigments on canvas.

On the right, Sahaja Cakrasamvara with Vajravarahi (16th c., Tibet), silver, copper and gilt-copper. On the left, Vajrapani (16th c., Tibet), represents an unwavering ability to vanquish negativity.

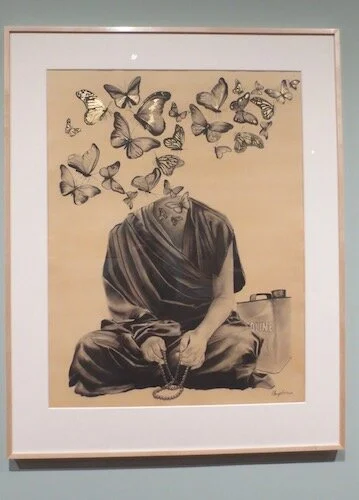

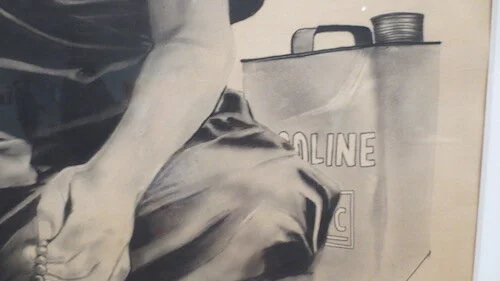

References to self-immolation appear in several other works. Although violence is done to one’s body, Tibetans recognize the self-sacrifice as an act of determination for the entire community. The images can be calm and beautiful, softly rendered, despite the harsh subject they point to.

“Ahimsa” [“non-violent protest”] (2016), by Chungpo Tsering. Charcoal and gold leaf on paper.

Detail of “Ahimsa” (2016), by Chungpo Tsering.

“Gas Can” (2012), by Tsherin Sherpa. Archival ink, gold leaf, and gouache on paper.

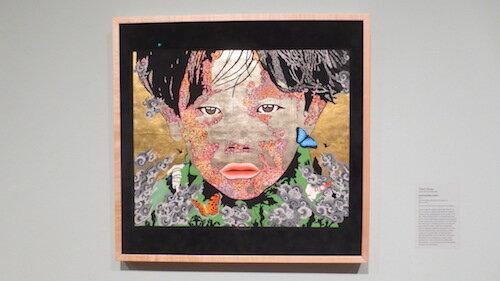

“Gold Child/Black Clouds” (2013), by Tsherin Sherpa. White and yellow gold leaf, acrylic, alcohol ink, glitter on linen.

Detail of “Gold Child/Black Clouds” (2013), by Tsherin Sherpa.

Three videos offer further examples of combining new technology with ancient practices. In her 2018 video, Marie-Dolma Chophel, born in France in 1984, works with illusory mountainscapes. She hand-pours sand, which is traditionally used for Tibetan Buddhist mandalas, onto pre-existing forms to create new ridges, slopes, and crags. Eventually, these give way into the reality of a pile of sand and break the illusion of a landscape. Then she sweeps away the sand and reveals an underlying painted image. Tsewang Tashi’s 2010 video refers to the dissonance between Tibetan and Chinese cultures in Lhasa, as does Benpa Chungdak’s 2003 performance on video. It shows him at the intersection of Beijing Middle Road and Dekey Road in east-central Lhasa, where devout practitioners holding prayer wheels are on a circumambulation route as dogs bark, cars honk, and Chinese restaurants feature lavish banquets. Everyone is trying to adjust to unprecedented circumstances in Tibet.

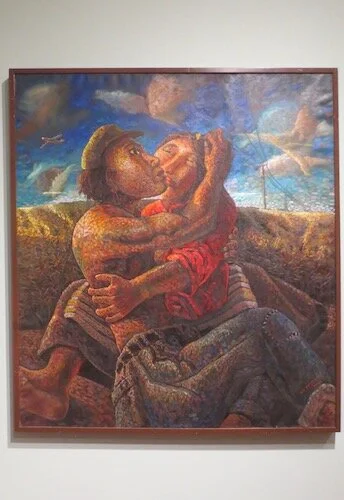

“Lovers, No. 6” (2003), by Tsering Nyandak. Oil on cotton canvas. Created in a near-pointillism style, this contemporary version of the traditional father-mother (yab-yum) pairing is both rustic and modern, with an airplane, electrical lines, and odd clouds as part of the scenery.

Detail of “Lovers, No. 6” (2003), by Tsering Nyandak.

Given similar situations other groups are facing as well, I wouldn’t surprised to see more diaspora art appearing from every part of the planet. Haven’t artists always had a need to express what they’re experiencing?

Comments and Questions:

If you consider yourself a diaspora artist, how does your art reflect your transcultural experience?

Is it futile to try to preserve ancient indigenous traditions? Is it more viable to hybridize or should we make every effort to keep one’s heritage alive?

What other diaspora artists are you aware of from different parts of the world? How do they combine aspects of various cultures in their art? What impact, if any, does their art have on you and your work?