What's Underneath?

When you look at a painting, do you ever wonder what’s underneath the image you’re viewing? Have you imagined what secrets might lie hidden below the surface?

There’s a long tradition of underpainting. An artist applies an initial layer of paint to the surface which acts as a base and defines color values for all the paint applications to come. Some artists treasure this phase of the process because they find it terrifying to face a blank canvas. Spreading a color across the empty expanse is a way to break through that fear and get started.

underpainting and finished work, Evening Flight by Jan Blencowe. Source: jerrysartarama.com/blog/

But that’s not the kind of underneath I’m referring to. Rather, what else might we discover beneath the picture in front of us? Did the artist paint something and then change her/his mind and depict a different landscape, portrait, or still life? Or was there an element in the composition that the artist simply decided to eliminate, for whatever reason?

For centuries, it was not possible to discern what was beneath the finished version of a painting. But the development of technological innovations has enabled us to perceive what exists under the many layers of paint. It’s as though we can peer into the mind of the painter and get a glimpse of earlier ideas and images to understand the process behind the artwork. Or, in yet other cases, might it be a sleight of hand by another person?

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (circa 1657-59), by Johannes Vermeer. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Take Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, by Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). To the young woman’s right is a blank wall. In front of her a window is wide open and, to her left, drapery is pulled aside. In her hands is a letter, the contents of which we are not privy to. This was the domestic scene art viewers witnessed for a good deal of the painting’s life.

Then came a surprise. The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, Germany, where the painting has been housed for a very long time, revealed a secret hidden below layers of paint. After a laboriously slow and meticulous restoration over a period of four years, the wall is no longer empty. Instead, it contains a huge painting of Cupid, which was first discovered by X-ray in 1979.

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (circa 1657-59), by Johannes Vermeer. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

The assumption was that Vermeer had done the overpainting himself because it was not uncommon for him to rework his compositions until he achieved a certain harmony. But when conservators started to clean the painting, they found inconsistencies in varnish and paint. It took two and a half years to painstakingly chip away at layers of paint with a medical scalpel under a microscope of 120x magnification. They could cover only a few square millimeters per day. In an archaeometry laboratory, dirt was discovered between those layers, indicating that someone other than Vermeer had added the overpaint at a later time, maybe in the early 1700s. Who did it, where, and why remains a mystery.

Cupid, the Roman god of love. Detail from Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (circa 1657-59), by Johannes Vermeer.

However, the image of Cupid might be a clue as to the unknown message of the letter. The appearance of the Roman god of love may hint at affection and yearning, an amorous relationship or the desire for one. Aesthetically, I prefer the empty wall, for it allows me to focus more on the young woman and what’s immediately around her, rather than having my eyes drawn to the outsized Cupid. The blank wall makes me envision more possibilities for the letter-reader.

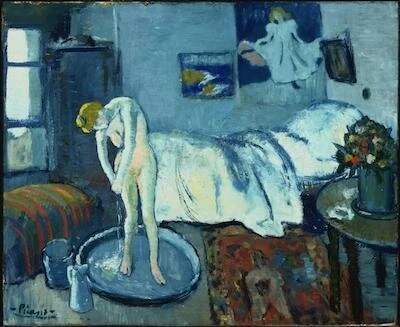

The Blue Room (1901), by Pablo Picasso. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Source: phillipscollection.org

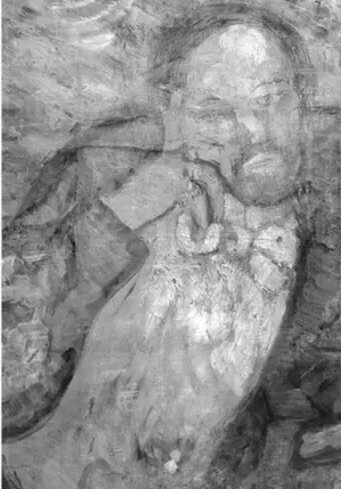

There are many other examples of overpainting as well as a variety of explanations to go with them. One was the simple fact of being too poor to purchase a new canvas when a painting proved unsatisfactory. This was common practice for Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) when he worked on The Blue Room in 1901. Infrared reflectography points out that this piece from his Blue Period was painted on top of an earlier portrait of a bearded man wearing a jacket and bow tie and resting his hand on his cheek.

Painting underneath The Blue Room (1901) by Pablo Picasso. Source: BBC via mentalfloss.com/

Why a seascape by Dutch marine artist Hendrick van Anthonissen (1605-1656) was overpainted is, like Vermeer’s work, another conundrum. According to conservator Shan Kuang at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England, it was puzzling why people were clustered on the sands, or peering down from the dunes, merely to look at a bleak stretch of a windswept beach in the winter. It was only after she skillfully took a scalpel to the painting that she found the answer.

View of Scheveningen Sands (1641), by Hendrick van Anthonissen. Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. Source: news.artnet.com/

In 2014, Kuang described the delicate process she went through. As she slowly removed the varnish from the painting’s surface, lo and behold, a floating figure gradually emerged on the horizon line, followed by a fin. Eliminating more paint eventually disclosed an entire beached whale, which substantially alters the composition and elicits the viewer’s attention. Suddenly, it is no longer a quiet, chilly, waterfront vista but an unexpected drama on the beach.

View of Scheveningen Sands (1641), by Hendrick van Anthonissen. Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. Source: en.wikipedia.org/

When French post-Impressionist artist Georges Seurat (1859-1891) created a portrait of his mistress Madeleine Knobloch applying makeup, he also concealed an image of himself. But for an entirely different reason than Picasso’s, he covered over it. Knobloch was an artist’s model with whom his affair was a secret. Supposedly, a friend of Seurat, ignorant of this liaison amoureuse, commented that the portrait appeared comical to him. Seurat, embarrassed by this remark, painted over his only self-portrait.

Young Woman Powdering Herself (1888-1890), by Georges Seurat. Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

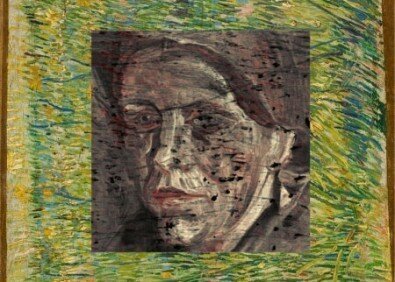

Patch of Grass, by Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) is another instance of a ghost figure in a painting. Under the brightly colored and exuberant nature scene is a serious portrait of a peasant woman. The artist possibly painted her early in his career, when he resided in the Dutch town of Nuenen in late 1884 and worked with peasant models in their cottages to create a series of portraits. It is believed he did this to master his control over light and color.

Patch of Grass (1887), by Vincent van Gogh. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Detail of underpainting of Patch of Grass, (1887),

by Vincent van Gogh.

So was the woman’s portrait simply a practice piece to be discarded later? Did he paint over the woman’s image because, usually penniless, he needed the canvas? Or had his focus shifted from people’s faces to the outdoors? Did he turn to vivid colors and a different style because of a change in his own mood? Perhaps he describes the shift in one of the many letters he wrote to his brother Theo. In any case, it happened quickly, from 1884 to 1887. And an interesting note is that this painting was one of the first to be analyzed by an X-ray technique that is able to accurately determine the original pigments of the hidden portrait. Dutch scientists Joris Dik and Koen Janssens invented the technology.

Mary Queen of Scots underneath a painting of Sir John Maitland, a Scottish nobleman. Courtaulde Institute of Art, Cambridge, England. Source: independent.co.uk/

Ghostly images appear in many more paintings, including but not limited to Picasso’s The Old Guitarist, Ingres’s Portrait of Jacques Marquet de Montbreton de Norvins, Rembrandt’s Old Man in Military Costume, van Gogh’s Still Life with Meadow Flowers and Roses, Goya’s Portrait Of Don Ramon Satue, Millet’s The Wood Sawyers, Malevich’s Black Square, and da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Artists, whether they work with paint, textiles, thread, paper, clay, wood, stone or metal, are always at liberty to change their mind and come up with a different composition, design, or color. From one change to another, the creative juices keep flowing. If a piece doesn’t turn out as anticipated, there’s always the opportunity to transform it into something else.

Questions & Comments:

If you’re a painter, how do you use underpainting and/or overpainting in your work and why?

If you use other materials, how do you alter a work when you want to do something different? What if you’ve already chipped away at the marble, stitched fabrics together, woven a length of tapestry, or dyed cloth but weren’t happy with the color?