Still Life, Art of the Inanimate

Still Life with Mice (1619), by Lodewik Susì. Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Anyone who has studied the history of art and/or walked through a museum housing the gamut of art genres will have seen still-life paintings. The term itself has long struck me as odd. How can life be still? Even when we sit quietly in meditation, the body is not completely motionless. While breathing in and out, our torso expands and contracts. Otherwise, we’d be dead! Many still-life works do contain dead creatures as well as flowers, fruits, and vegetables no longer hanging on trees or stalks. They also include human-made objects.

Still Life found in the Tomb of Menna (1550–1069 B.C.E.).

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

I learned that the term comes from the Dutch word stilleven, for the genre as we recognize it seems to have gained ascendancy in the Netherlands during the 16th and 17th centuries. Yet there is evidence of such compositions in Egyptian tombs, on ancient Greek vases and Roman walls, and as early as the 11th century in East Asia. Maybe natura morta or nature morte (“dead nature”) would be more accurate than “still life.” And, anyway, no painting is truly alive, except in our imagination.

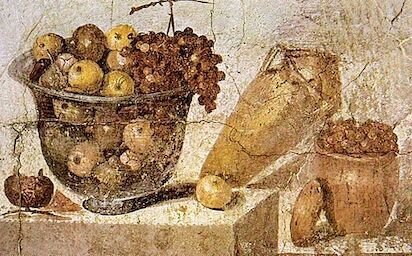

Natura morta con fruttiera di vetro colma e vasi (before 79 C.E.). House of Julia Felix, Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

While I am accustomed to think of still-life art as comprising various food items, flowers, and dead game or fish, some artists arranged other kinds of inanimate objects. The one below by Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627-1678) seems of a more modern era than the 17th century.

Trompe-l'oeil still-life (1664), by Samuel van Hoogstraten. Dordrechts Museum, The Netherlands. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

But certainly not as modern as A Painter’s Table by Canadian-American artist Philip Guston (1913-1980).

A Painter’s Table (1973), by Philip Guston. Source: nga.gov/.

© The Estate of Philip Guston.

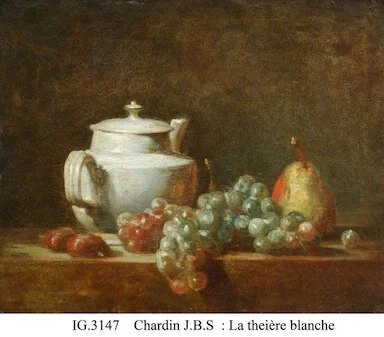

Over the centuries, still-life styles have, of course, changed. I remember viewing pictures in which the objects appeared quite real, so three-dimensional and eminently edible. Yet a closer look always revealed they were not. There was no actual food, only paint strokes on a substrate. As Siri Hustvedt has pointed out in Mysteries of the Rectangle: Essays on Paintings, “Like all mimetic painting, traditional still life is in the business of illusion. Only a mad person would reach out to take a grape from a Chardin canvas in order to eat it, and yet the fact is that the painting of a table laid for dinner, flat as it is, bears a resemblance to the reality of the things it refers to by virtue of its deadness.”

La theière blanche (18th century), by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779). Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

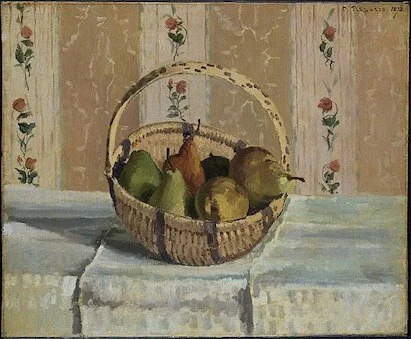

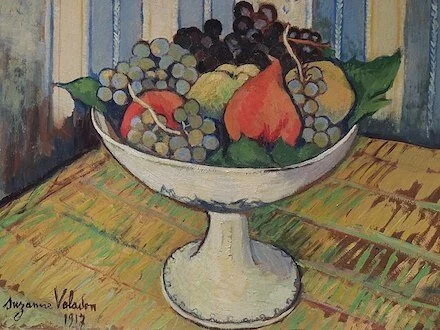

In more abstract renditions of fruit and flowers, such as those by Impressionists and Cubists, I no longer imagine I can reach out and eat them!

Still Life: Apples and Pears in a Round Basket (1872), by Camille Pissaro. Princeton University Art Museum.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Bowl of Fruits (n.d.), by Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938), Musée de Montmartre, Paris. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Nor do I consider drinking from the bottles and goblets.

Still Life (1915) by Ilmari Aalto. Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

And I certainly can’t smell the flowers. These artists were not trying to scientifically capture what was in front of them. Rather they were experimenting.

Lilacs in a Window (1880s), by Mary Cassatt. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Sunflowers (1889), by Vincent van Gogh. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

As different art movements have come and gone, their still lifes reflect the times in which they were created. For example, the flower arrangement by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573-1621) represents a trend in the Netherlands and Germany at the end of the 1500s. A rising interest in botany and a passion for flowers led to an increase in painted floral still lifes. Bosschaert, the head of a family of artists, rendered flowers with scientific accuracy. Sometimes they included symbolic and religious meanings. In the painting below, the butterfly, dragonfly, and flowers remind the viewer of the brevity of life and the transience of its beauty. Considered the first great Dutch specialist in fruit and flower painting, he established a tradition that influenced an entire generation of such artists in the Netherlands.

Flower Still Life (1614), by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder. The Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Bosschaert might have influenced Clara Peeters (1594-after 1657). Like Bosschaert, she was born just over the border in Belgium and later moved to the Netherlands. Since women were restricted from learning how to portray human figures from life, that pretty much eliminated paintings of people. However, still life, the least prestigious genre, was available to them. By the time she was 18 years old, Peeters was producing large numbers of painstakingly created still lifes, often groupings of such valuable objects as elaborately decorated metal goblets, gold coins, and exotic flowers. These were in keeping with the moral belief that all is vanitas, the futility and limits of our earthly existence. Her work was successful internationally.

Still Life with Venetian Glass, Roemer and a Candlestick (1607), by Clara Peeters. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Despite the initial emphasis on vanitas, over time Peeters also began to celebrate the earthy pleasures of food. As poet Mark Nepo has remarked, “The extraordinary is waiting quietly beneath the skin of all that is ordinary.”

Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels (c. 1615), by Clara Peeters. The Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Another woman painter who took up still life was the Dutch artist Maria van Oosterwijck or Oosterwyck, (1630–1693). Among her patrons were Louis XIV of France, the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, Augustus II the Strong, William III of England, and the King of Poland. Although her skillfully executed paintings were in high demand by Dutch and other collectors, because she was a woman, she was barred from membership in the painters' guild.

Flower Still Life (1669), by Maria van Oosterwijck. Cincinnati Art Museum.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744-1818) had a better situation in that, at the age of 26, she was elected as an associate and a full member of the Royal Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture and became a major 18th-century painter in France.

Attributes of Music (1770), by Anne Vallayer-Coster. Louvre Museum, Paris. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

During the Joseon period of Korea, from the second half of the 18th century to the first half of the 20th century, chaekgeori ("books and things") were an especially popular genre of still-life painting in which books are the dominant subject, along with writing implements used by scholars, luxury goods, and gourmet delicacies, all neatly arranged. The chaekgeori or chaekgado were appreciated by the entire population, from King Jeongjo (1752-1800), a bibliophile who promoted studious learning, to the commoners, who decorated their homes with them.

Chaekgeori (late 19th century), artist unknown.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Detail from chaekgeori (late 19th century), artist unknown, 6-panel screen. Ink and color on paper, 59" (H) x 114" (W). Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Some still-life art from Japan, such as the one below by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), also incorporates poetry. In the upper part of the print, two poems focus on the theme of cherry blossoms. They were composed by Asakusa-an (1755–1821) and his contemporary Teika-an.

These and other still lifes from East Asia never purported to be realistic, as in the style of European painters. There’s a softness to them, rather than a sharp photographic likeness. They do not pretend to be real.

Still Life: Double Cherry-Blossom Branch, Telescope, Sweet Fish, and Tissue Case (ca. 1804–13). Source: metmuseum.org/

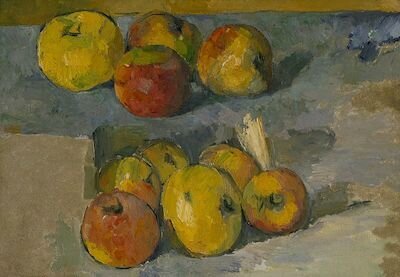

Food writer Ruth Reichel remembers a professor she had long ago. One day in class, he announced that the next lecture would be dedicated to the food of French artist Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). When he showed a slide (pre-digital era) of Apples, he told the students that the painter had once said to a friend that fruits “love having their portraits done” and that he wanted to “astonish Paris with an apple.” When she stared at the painting, Reichel found herself not at all astonished. The apples were not apples. They were not three-dimensional fruit but two-dimensional art. Was that Cézanne’s point?

Apples (1878-1879), by Paul Cézanne. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

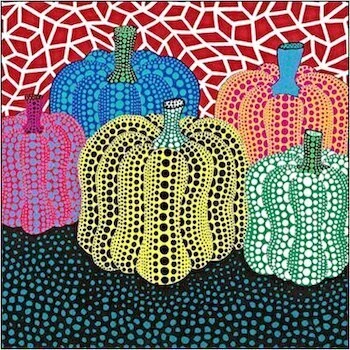

And Yayoi Kusama’s pumpkins are not pumpkins.

Pumpkins (n.d.), by Yayoi Kusama. Source: https://www.sketchbookstudiosf.com/camps-1/yayoi-kusama-fall-pumpkins

So what is it about these compositions of mundane objects that draws us in, even if we’re not astonished? Hustvedt captures their appeal:

Still life is the art of the small thing, an art of holding on to the bits and pieces of our lives. Some of these things we glimpse within the frame of a painting are ephemeral—food, cut flowers, tobacco—and others, like the clutter in a dead man’s attic, are objects that will survive us….[T]he space inside the frame is a figment and the things it holds are imaginary….Because the objects of still life are ordinary—a sausage, a melon, a bowl, a boot—their translation into paint intensifies them. They are dignified by the metamorphosis we call art.

Questions & Comments:

If you’re attracted to still lifes, what is it about them that you find interesting, stimulating, pleasurable?

How are artists today working in this genre? Are any hearkening back to the old masters, adding a feminist touch, going completely contemporary, displaying the objects that are so much a part of daily life now?