Trashing Your Art: Why?

When we talk about art, we generally refer to creativity rather than to destruction. Yet destruction can also be part of the creative process. Different artists have different reasons for engaging in the obliteration of their work. Art collectors cringe at the thought of “lost” artworks, while museums bemoan their absence for a retrospective. However, the decision to save or to demolish is in the hands of each artist.

Waterloo Bridge (1904), by Claude Monet.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

French artist Oscar-Claude Monet (1840-1926) destroyed many of his paintings out of despair over their quality. Before a 1908 Paris exhibition alone, he slashed anywhere from 15 to 30 of them. At other times, he would thrust his foot through a canvas or throw his easel into the river. None of the annihilated paintings had reached his high standards. In a hopeless mood, he once said, “My life has been nothing but a failure, and all that’s left for me to do is to destroy my paintings before I disappear.” The value (not just monetarily) of his work today belies his self-doubt.

The Deposition (Florentine Pietà or The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1547-1555), by Michelangelo. Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

It was rare for artists to intentionally damage their work in much earlier times—that is, before the art market and its galleries emerged in the eighteenth century—because raw materials for paintings and sculptures were too exorbitant to squander. Nevertheless, Michelangelo (1475-1564) trashed many of his drawings and preparatory sketches. According to Noah Charney, in The Museum of Lost Art, the Italian artist sought to make a final masterpiece appear even more spectacular by presenting it as having sprung whole from a blithe creative genius rather than from a man who labored in a scrupulously meticulous manner. Michelangelo also violently attacked The Deposition with a hammer after working on it for eight years. A church official rescued and partially restored it, but Christ’s missing leg was never replaced.

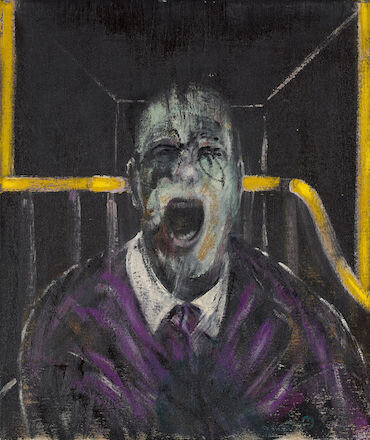

Study for a Head (1952), by Francis Bacon.

Source: www.artsy.net/

After Irish-born British artist Francis Bacon ( 1909-1992) died, a great deal of destruction was evident. His home and his studio in South Kensington (like the untidy one in Dublin in the photo below), which was already littered ankle-deep in art materials and non-art objects, contained hundreds of canvases that Bacon had vandalized. According to the Tate, one of them, Study for Man with Microphones, was completed and exhibited twice in 1946. Some time between then and a 1962 exhibit at the Galleria d’Arte Galatea in Milan, Bacon reworked the unsold composition and presented the revised form as Gorilla with Microphones. Although this was a case of transforming an older work into a newer one, too many other canvases became the fatal victims of Bacon’s violence.

Francis Bacon’s studio in Dublin, Ireland.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

As the Tate informs, the artist found it hard to finish his paintings; he had to discard canvases that became too clogged with pigment. Bacon also regularly destroyed works that he was disappointed with. That’s why, in the piles found on the studio floor after Bacon’s death, there were portraits with faces cut out. Against windows and walls, larger slashed works were stacked. “In some cases the damage had evidently been inflicted even while the paint was still wet. In others, the fracturing of the dry paint showed they had been cut long after completion." This was the case with Gorilla with Microphones: Two large sections were cut away from the center of the canvas, but they were found in the same room. Although Bacon had radically reworked the original painting, he later destroyed it again. The Tate concludes that it is “a tangible reminder that artists sometimes destroy works as part of a pained and tortuous creative process.” And sometimes an artist reconsiders and looks back at those destroyed works as among the best, as Bacon did.

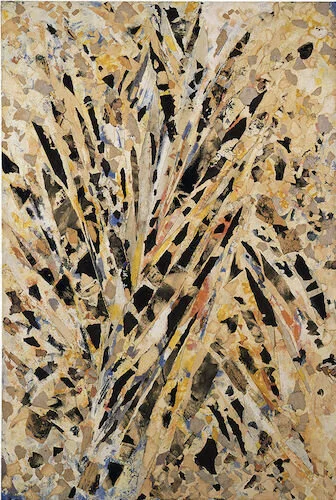

Lee Krasner: Collage Paintings 1938-1981. Exhibition (March 11-April 24, 2021) at Kasmin Gallery, New York. Photo by Diego Flores.

Source: www.kasmingallery.com/.

What got me thinking about the creation/destruction dichotomy of the artistic process was a recent Zoom presentation on the collage paintings of American artist Lee Krasner (1908-1984), on exhibition at Kasmin Gallery in New York until April 24. Creativity might lead to a finished piece that the artist accepts, maybe even celebrates. On the other hand, the same piece might elicit dissatisfaction followed by destruction. But, depending on the artist, that doesn’t always spell the end of it.

Stretched Yellow (1955), by Lee Krasner. Oil with paper on canvas. Collection of Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld, Contemporary Art Museum of California State University, Long Beach. Source: kasmingallery.com/

When Krasner considered some of her paintings unsuccessful in the early 1950s, she tore, slashed, and cut up the canvases. The act seems reminiscent of something her teacher, German-born artist Hans Hoffmann (1880-1966), did one day in class: He picked up her sketch, ripped it, and repositioned the pieces. Also inspired by Matisse and his cutouts, Krasner turned her demolished paintings into raw materials for collages.

Burning Candles (1955), by Lee Krasner. Oil, paper, canvas on linen. Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York. © 2015 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo ©Jim Frank. Source: purchase.edu/

Decades later, Krasner would revisit this process. In an interview conducted by Eleanor Munro, she explains that her tendency to revision and repurpose her paintings and charcoal drawings can be attributed to her belief in paying attention to cycles. Krasner said about her paper and canvas collages: “Obviously I’m hauling out work (drawings) of 30 years ago…Dealing with it. Not ignoring, hiding it. I’m saying, here it is in another form. This is where I’ve come from: from there to here. It gives me a kick to be able to go back and pick up 30 years ago. It renews my confidence in something I believe. That there is continuity.”

To the North (1980), by Lee Krasner. Oil and paper collage on canvas. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Source: dreamideamachine.com/

The delightful conversation between Eric Gleason, Senior Director at Kasmin, and London-based curator and art historian Katy Hessel, founder of The Great Women Artists, describes Krasner’s abandonment of early works and her later reinvention of them as collage paintings. Gleason quoted her: “I am not to be trusted around my old work for any length of time.” In her creative process of recycling, Krasner was reflecting a transformation of herself as well. As she evolved her artistic expression through various periods, she incorporated the past—what she had destroyed—while giving birth to fresh compositions.

If you’re interested in viewing the exhibit and listening to the conversation, here’s the video from Kasmin Gallery.

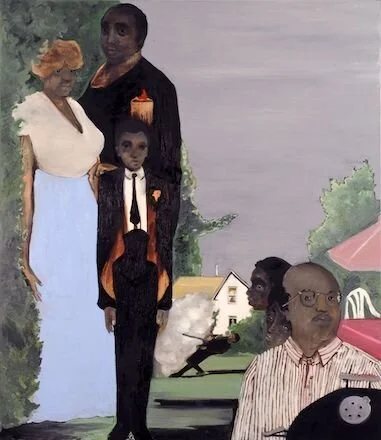

Like Russian avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) and Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Noah Davis was not averse to painting on top of another painting. Born in Seattle in 1983 and then based in Los Angeles, Davis died at 32 of a rare form of soft tissue cancer in 2015. He was prolific in his short life, producing some 400 paintings, collages, and sculptures. He worked so quickly that others couldn’t keep up with him. As Bennett Roberts, founder of Roberts Projects in Culver City, California, has said, “The only problem with Noah [was that] he would call me and say, ‘Come to the studio, I painted 10 great new paintings.’ He was very fast when he was working. I’d go in there and just be mesmerized. ‘These are unbelievable, can we get them to the gallery? I’ll photograph them.’ Two days later, he would say, ‘Oh, sorry, I painted over every one of them.’” Was it because another idea grabbed hold of him in an instant that he couldn’t stop to prime a blank canvas or did his vision of the painting simply change too dramatically to let the first “draft” be?

The Last Barbeque (2008), by Noah Davis. Source: www.artsy.net/ (Courtesy of Roberts Projects).

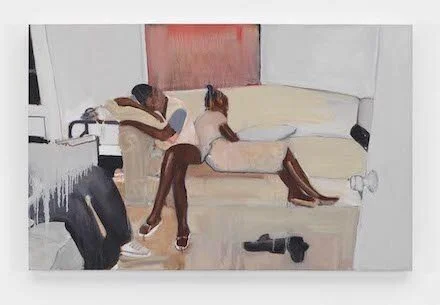

Untitled (2015), by Noah Davis. ©The estate of Noah Davis.

Source: news.artnet.com/

The artists I’ve mentioned belong to a long line of creatives who have similarly rid themselves of old work as they moved forward. Some burn their oeuvre (notably, John Baldesarri), others slash or paint over. Maybe they don’t want to be associated with the figurativism or social realism they once engaged in since now they consider themselves part of the abstract art community, or vice versa. Perhaps they’re trying to make a political point. For others, destruction of their art might be the result of insecurity or madness, even disgust with not achieving their vision. Whatever the reason, doing away with art pieces can also be an indication of courage, a bid for liberation from a specific form or style or medium. By wiping the slate clean, an artist enters an open space in which to discover even more creativity.

Questions and Comments:

Do you destroy work you’ve created and, if so, what is the impulse behind doing that?

What other artists come to mind when you consider destruction as part of their creative process?

How can destruction benefit an artist? How can it harm an artist?