Art and Sibling Rivalry

What if your sister or brother is also an artist? What if you both paint or sculpt or dance? What if you both weave or compose or play the same instrument? Do you encourage and support each other or do you compete? Does resentful rivalry take over, leading to separation? Who gets to shine and who remains in the shadows? Who achieves world renown and who is forgotten?

Sisters Ida and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Source: okeeffemuseum.org/

What brought on all these questions was a brief notice I came across in Smithsonian Magazine (December 2018) about “The Other O’Keeffe: The painter who toiled in the shadow of her celebrated sister.” I wondered who that was, for the only O’Keeffe whose artwork I was familiar with was Georgia (1887-1986). I was taken aback to learn that Ida O’Keeffe (1889-1961) was considered the more talented of the two, at least by their family. But it was Georgia who became an iconic figure in 20th-century art. How did one publicly win out over the other, and what did that mean for sisterhood?

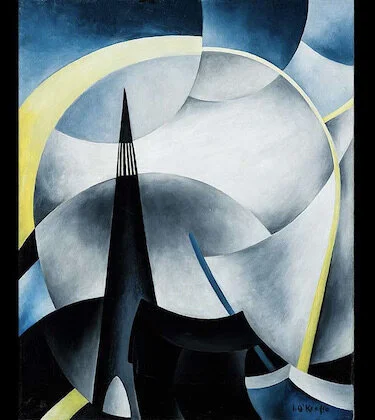

Variation on a Lighthouse Theme V (ca. 1931-32), by Ida O’Keeffe. Oil on canvas. Dallas Museum of Art.

Source: smithsonianmag.com/

It was only when I started reading about Ida that I also learned about another sister, Catherine O’Keeffe Klenert (1895-1987). The two of them, along with Georgia, were born into a middle-class family in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. Out of seven siblings, the five sisters were all taught drawing. In 1927, when Georgia curated a show at the Opportunity Gallery in Manhattan, she included the work of her sisters. At the time, Ida exhibited as Ida Ten Eyck so as not to be compared with Georgia. Then, in late 1932, the Delphic Studios, another contemporary art gallery in New York, showed work by Catherine and the sisters’ grandmothers, themselves artists. Two months later, Ida, followed with a solo show there. Once critics hailed the O’Keeffe sisters as a “Family of Artists,” an enraged Georgia demanded that her siblings forsake art and stop showing their work. This forever transformed sisterly affection into estrangement. Georgia broke communication with Catherine for four years, but eventually sent her a letter of apology. Stung by Georgia’s vituperation, Catherine ceased to paint. Ida, on the other hand, refused to give up, though she left New York and never reconciled with Georgia.

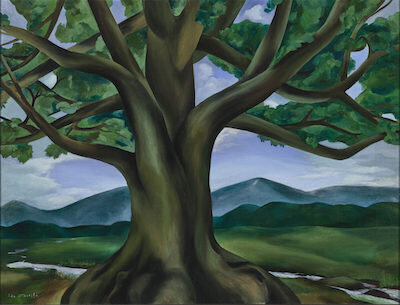

The Royal Oak of Tennessee (1932), by Ida O’Keeffe. Private Collection, New York. Source: apollo-magazine.com/.

Supposedly, Ida complained that she’d be famous too if she’d had a Stieglitz as her patron. [Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), at the center of American Modernism with his Gallery 291, brought Georgia to New York and financially backed her so she could leave her teaching job at West Texas State Normal College and begin to paint full time, and then boldly promoted her.] Unwilling to respond to his flirtatious innuendos with anything but friendship, Ida supported herself as a nurse and also taught art. While Georgia’s star rose with Stieglitz’s support, Ida’s art career never reached any heights during her lifetime until Sue Canterbury “discovered” her in 2013.

Variation on a Lighthouse Theme IV (ca. 1931-32) by Ida O’Keeffe. Oil on canvas. Source: newyorker.com/Courtesy The Clark Art Institute.

During a visit to a Dallas art collector, Canterbury, now The Pauline Gill Sullivan Curator of American Art at the Dallas Museum of Art, found herself drawn to a particular painting. It was “a lighthouse composed of dozens of swooping abstract blue, black, and gray segments, fragmented as though viewed through a kaleidoscope.” Not recognizing who the artist might be, she took a closer look and found the signature: Ida O’Keeffe. Despite her expertise, Canterbury wasn’t aware that Georgia’s younger sister was also an artist. After five years of extensive research to uncover Ida’s previously unexplored biography and practice, Canterbury organized Ida’s first solo museum exhibition of paintings, watercolors, prints, and drawings: Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow. Both the exhibition and the catalogue examine the obstacles that frustrated Ida’s professional ambitions as well as how art eventually led to breaking the close bond between her and Georgia. Ida O’Keeffe had its debut at the Dallas Museum of Art in November 2018 and then opened at The Clark Art Institute in July 2019.

Star Gazing in Texas (1938), by Ida O’Keeffe. Oil on canvas. Dallas Museum of Art. Source: collections.dma.org/

One by one, Ida’s works were brought out of oblivion. They had been sold for a pittance, including at a flea market and thrift shop. Their appearance in public not only casts a brighter light on Ida, but a darker one on Georgia. As Canterbury points out, “She [the latter] wasn’t particularly supportive of other women artists. It speaks to Georgia’s insecurities, in spite of her fame at that time.”

Creation (c. 1936), by Ida O’Keeffe. Oil on canvas, 23 x 28 in. Source: themagazineantiques.com/

Courtesy Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe.

But it wasn’t only a sister who thwarted Ida. An interview with curator Gordon Gilkey (1912-2000), who studied printmaking with her in the late 1930s, indicates that Stieglitz convinced a dealer in New York not to exhibit Ida’s work. Was he pressured by Georgia or was it his own reaction after Ida rebuffed his flirtations? How odd to do so when he had once written to journalist Paul Rosenfeld in 1924: “Ida is truly an artist, too, if ever there was one. She has done things in that way which compare with Georgia’s best paintings—the same spirit—the same balanced sensibility—the amazing feel for color and texture.”

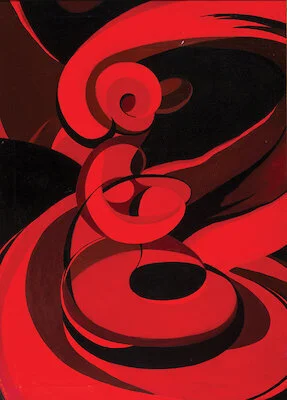

Whirl of Life (1936), by Ida O’Keeffe. Oil on canvas. Collection of Paul and Sherlea Taylor. Source: themagazineantiques.com/

photo© 2018 Dallas Museum of Art.

For a view of the exhibit and comments about Ida and her work, here is a short video.

The O’Keeffe sisters were not the only siblings to experience artistic antipathy. On June 20, 1993, The New York Times reported on the first show in which sculptures by the Borglum brothers—Gutzon (1867-1941), of Mt. Rushmore fame, and Solon (1868-1922)—were exhibited together. Competitors that focused on different styles and subjects, they did not get along. According to the article: “Their lasting rivalry stemmed from Solon's breaking his promise that he would remain a painter and not venture into sculpture. Gutzon tried to obliterate the fact that Solon was even related to him.”

Part of Wars of America (1926), by Gutzon Borglum. Military Park, Newark, New Jersey. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

“Indian Love Chase” (1899), by Solon Borglum. Bronze. New Britain Museum of American Art. Source: ink.nbmaa.org/

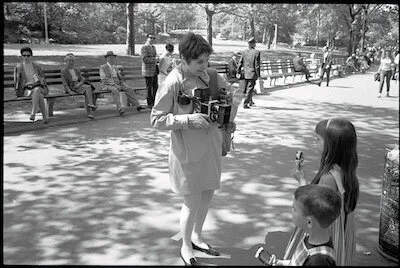

Sometimes sibling competitiveness exists even between different mediums. In his book Silent Dialogues, art historian Alexander Nemerov notes that his father, former U.S. Poet Laureate Howard Nemerov (1920-1991), and his aunt, photographer Diane Arbus (1923-1971), shared a similar quest for a kind of spiritual revelation in their respective arenas. Yet, instead of mutual support, the poet, prejudiced against photography, was dismissive of his younger sister’s efforts. But that disregard actually clarified for Arbus what and how she would photograph. Once he began to see her photographs not as grotesque and odd but rather revelatory, Nemerov’s poetry practice nosedived into a writer’s block that lasted two years. She had achieved what he’d once had ambitions for himself.

Diane Arbus, New York City. Source: artnews.com/.

Arbus’s reputation burgeoned and photography increasingly earned respect as an art. However, the fame she had aspired to did not come until after her suicide. A retrospective at New York’s MoMA the following year drew visitors that waited in lines winding around the block, and her monograph sold half a million copies. Only when looking into the Nemerov family did I learn there was still another sibling in the arts, sculptor/painter Renee Nemerov Sparkia Brown (1928-2012), who was overshadowed by her older sister and brother.

Jack Dracula, The Marked Man, photo by Diane Arbus. Source: port-magazine.com/

Competition has both benefits and downsides. For some artists, competing plays a vital role in pushing them to stretch and grow, while for others, it has an inhibiting effect, killing their curiosity and experimentation. Not everyone has the personality to withstand the pressure, especially when the rivalry is antagonistic rather than amicable. Do we give up our art because a sibling (or spouse) has a bigger ego and stronger drive? What do we need in order to follow our individual path in art, no matter who else is there striving for recognition and kudos? In the end, how much does creating mean to us?

Questions & Comments:

What other siblings in the arts were/are intensely competitive? Who became acclaimed and who remained in obscurity?

What siblings have worked together cooperatively rather than antagonistically?

What experiences have you had around this issue in your own art practice?