Windows in Art: Looking Out, Looking In

For most of us, windows are something we probably take for granted. They let in light and views and, if openable, air and sounds as well. Although glass-making took place some 3,600 years ago in Mesopotamia, and even earlier in Egypt, it didn’t produce the kind of windows we are familiar with. Not until the Renaissance did Italian glass blowers start to turn out relatively large and transparent glass. Previously, windows were small and dull. One could not gaze out and contemplate the beauty of the surrounding environment.

A Japanese garden scene through a window from the Keitaku-en chickee, Tennoji Park, Osaka, Japan.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

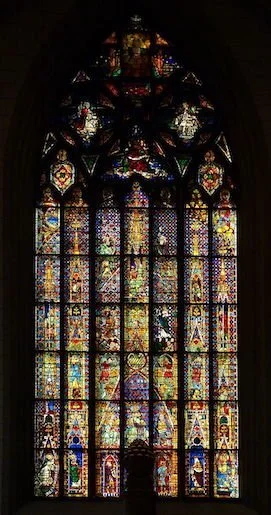

Before transparent windows became available, there were stained-glass versions. There is evidence of them in British monasteries as early as the 7th century. The building of great cathedrals and churches during the Middle Ages called for massive amounts of colored glass held together with lead. Given the illiteracy of the general population, the stained glass illustrated Bible stories and the lives of saints.

The Augsburg Cathedral, Roman Catholic church, Bavaria, Germany. The exact origin of the stained glass is debated as from the building’s consecration in 1065 or dated to first half of 1100s. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

After stained-glass windows, clear windows in artwork became not only architectural elements, but also atmospheric backgrounds and framing devices as well as symbolic motifs for hope, inspiration, aspiration, change, illumination, even spiritual vision. Windows serve as a transition between the interior (of a room or a person in it) and the exterior (landscape, seascape, or urbanscape). They may be representational or abstract. In some works, we are looking from the inside out and, in others, from the outside in, even unexpectedly into a person’s dream or philosophy. In yet others, we are doing both, observing from inside a window at the windows across the way.

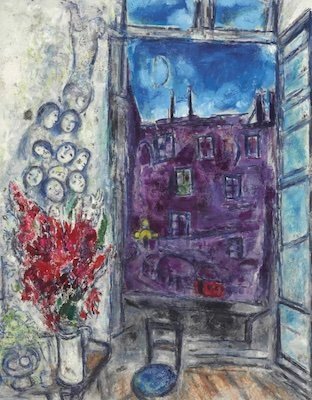

The Window (1959), by Marc Chagall.

Source: arthive.com/encyclopedia/

Although there’s some history to the images below, delving into it for every artwork would make this an overly long post. I also would rather leave you with some questions to reflect on, rather than describe all the paintings through my own lens:

What captures your attention?

What is the artist trying to convey by including a window or windows in the composition?

What do the various windows suggest to you—mythically, realistically, surrealistically, psychologically, religiously?

How important a role does the window play—central or incidental?

No matter what the artist intended, I imagine each of us will offer a different interpretation, based on our individual experiences. Please enjoy musing on the images below. Their range reflects how diverse something as ordinary-seeming as a window can appear. I hope they stimulate not only your own creativity, but also how you view windows from now on. Especially in times of confinement, such as a pandemic, real windows and windows in art allow us to move beyond the walls that might confine us.

The Dreyfus Madonna (Madonna with child and pomegranate), (1475-1480), by Lorenzo di Credi. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

The Return of Odysseus (Penelope with the Suitors), (1508-1509), by Pinturicchio. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

A Boy Blowing Bubbles (1663), by Frans van Mieris, the elder. Museum kunstpalast, Düsseldorf, Germany. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

The artist’s' wife, Caroline Friedrich, in Caspar David Friedrich’s studio, Dresden, Germany (1822). Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

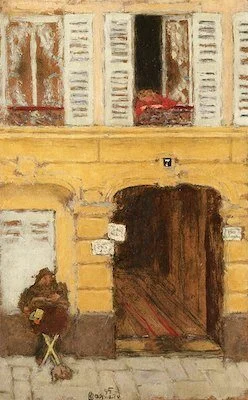

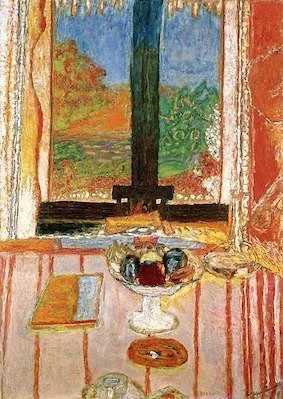

French painter, illustrator and printmaker Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) features windows regularly in his many boldly colorful paintings.

The Barrel Organ (date?),

by Pierre Bonnard. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Table in Front of the Window (date?), by Pierre Bonnard.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Russian-French artist Marc Chagall (1887-1985) offers a glimpse of Paris through a window.

Paris through the Window (1913), by Marc Chagall. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Source: guggenheim.org/artwork/793

French artist Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) created an entirely abstract city view through windows, one in a series.

Simultaneous Windows on the City (1912), by Robert Delaunay. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

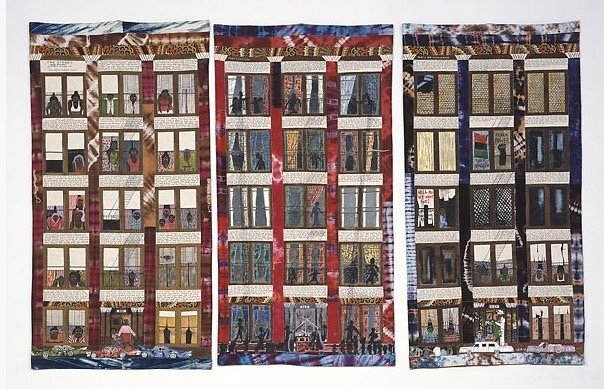

American artist and activist Faith Ringgold (1930-) conveys stories about African American life, history, and identity, especially in her resident community of Harlem. There are lots of windows in this triptych of quilted fabric that she painted with acrylic and embellished with sequins and printed and dyed strips of fabric. Each window has a story to tell about the person(s) in it.

Street Story Quilt (1985), by Faith Ringgold. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Source: metmuseum.org/

American modernist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) sparingly captures a window in her compound in Abiquiu, New Mexico.

Door Through Window (1956), by Georgia O'Keeffe. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Source: architecturaldigest.com/

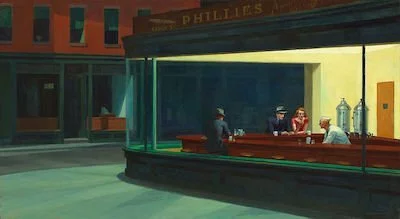

Whether we’re looking into the windows of a home or a business, what story is unfolding on the other side of the glass?

Nighthawks (1942), by Edward Hopper. Art Institute of Chicago. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

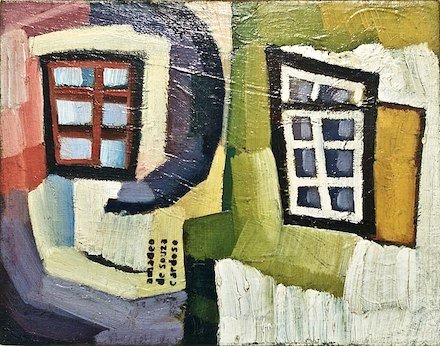

The Fisherman’s Window (c.1916), by Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso.

Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea do Chiado, Lisbon, Portugal. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

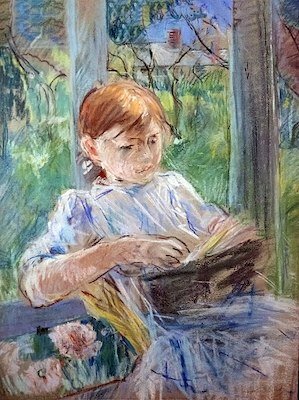

Reading, writing, or simply daydreaming by a window is a popular theme in the pastels of French artist Berthe Morisot (1841-1895).

Young Girl Reading (date?) by Berthe Morisot.

Fondation Bemberg, Toulouse, France.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Young Girl Writing (date?), by Berthe Morisot.

Source: wayfair.com/

Daydreaming (1877), by Bethe Morisot. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Source: art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/4465/

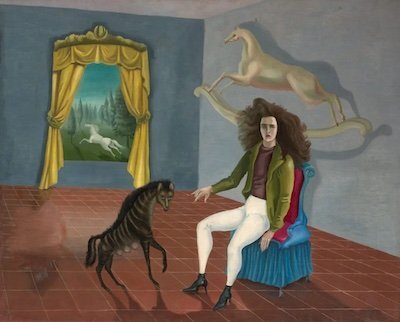

British-born Mexican artist, surrealist painter, and novelist Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) includes a window in her self-portrait. Does it represent a dreamscape?

Self-portrait (c. 1937-1938), by Leonora Carrington. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Source: metmuseum.org/

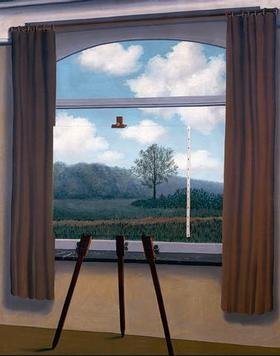

Also intriguing is this window by Belgian surrealist Réné Magritte (1898-1967). He explains in a letter to the Belgian poet Achille Chavée: “This is how we see the world. We see it outside ourselves, and at the same time we only have a representation of it in ourselves.”

The Human Condition (1933). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Source: en.wikipedia.org/

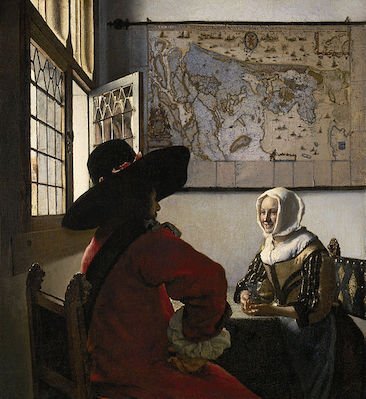

I can think of at least a dozen paintings by Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) that incorporate a window on the left side. Was it a device that enabled him to infuse his art with a signature kind of light or simply indicative of buildings in that time and place?

The Astronomer (1668), by Johannes Vermeer. The Louvre, Paris.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Officer and Girl (c.1657), by Johannes Vermeer. The Frick Collection, New York.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

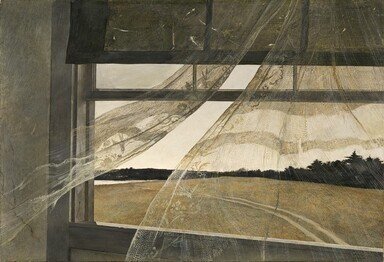

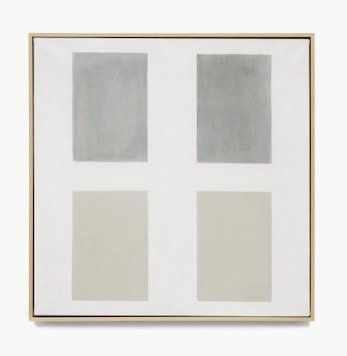

Although there are hundreds more works of art with windows, I’ll end with two in soft, neutral tones, a contrast to the brilliant colors used by Matisse, Bonnard, van Gogh, and others. I sense a quietness in these final two images—one representational, the other geometric—a stillness that easily induces one toward pensiveness. I can envision myself sitting by Andrew Wyeth’s window, smelling and feeling the sea air, letting thoughts blow away. I can also imagine myself gazing at Agnes Martin’s “windows” in open-eyed meditation. Both offer an opportunity to pause from the busyness of everyday life and perhaps to look inward.

Wind from the Sea (1947), by Andrew Wyeth. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Source: nga.gov/

Window (1957), by Agnes Martin. Dia Art Foundation, New York. Source: diaart.org/