Art and Time

Time is nothing we can grasp in our hands and yet we talk about it as a physical presence in our lives. It's simply how we measure the period in which an action, a condition or a process occurs. It's also the continuum in which one event succeeds another from the past through the present and into the future. It's real and virtual, historical and recorded. Some cultures conceive of time as cyclical; others map it linearly. While we can't control it, too often it controls us.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Recently, I listened to an audio version of Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. It’s not yet another dissertation on how to manage our time, but a series of insights from ancient and contemporary philosophers, psychologists, and spiritual teachers on the nature of time, so elusive and confounding to everyone who seems never to have enough of it. According to Burkeman, even the expression “to have time” or “not have time” is debatable. He gave me a lot to reflect on in general, but also with respect to art.

Sundial on Church of Saint Rupert in Šentrupert, Slovenia. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Reading about time reminds of Alice, who shrinks or grows larger as circumstances change in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. In art, there's the time it takes to create an object, be it a painting, tapestry, sculpture, or musical composition. When the process is running smoothly, it's as though time disappears; when we hit a snag, it seems to take forever.

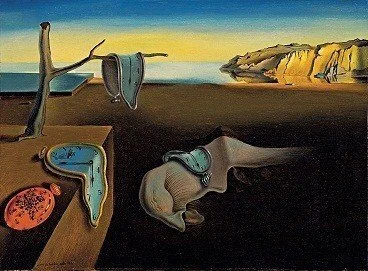

The Persistence of Memory (1931), by Salvador Dali. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

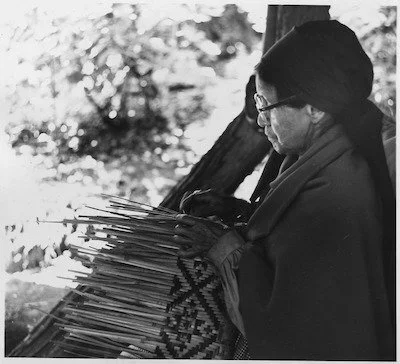

In Baskets as Textile Art, Ed Rossbach looks at the time involved in a creative activity through a particular lens. While he specifically addresses basketry, his perspective could just as easily apply to working with cloth and thread or canvas and paint. He suggests understanding basketmaking as more like music than a visual art:

...more of a time experience than a space experience...an experience in dividing and organizing time, breaking time into modular units...more complex than minutes and seconds, to be arranged in sequences and patterns. Basketmaking might be a sort of clock, not a measuring device, but something devised by [wo]man to enforce an awareness, a savoring, of time through its arbitrary division into rhythmic units.

Native American woman weaving a basket at Oconaluftee Village, NC. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

In our nano-second culture, how often do we savor time anymore? We feel the urgency of its passing as we rush to complete this or that task, to keep up with emails, texts, or tweets, to respond to the demands of work and family. Writing fifty years ago, Rossbach decried this aspect of modern life and suggested a different experience of perceiving time in an art object:

[W]hen a person says, upon looking at a basket or any other textile, "Think of the time it took to make it," [s]he may be doing more than merely illuminating...the distorted values which are part of the detestable illness of the [20th] century, that anything which takes time is not worth bothering with. It has become essential to feel a pressure of time, to reject anything which requires an abundance of time. And with such a rejection...we reject any full appreciation of what others are doing or have done. Yet by feeling "time" when [s]he confronts a piece of quilting or embroidery or lacemaking or basketry, the viewer may be close to the essence of the art.

Rossbach died in 2002, so I don’t know whether he was aware of the Slow Movement (slow food, slow art, etc.) that has developed to counter the pressure and poverty of time in the 20th and now also 21st centuries.

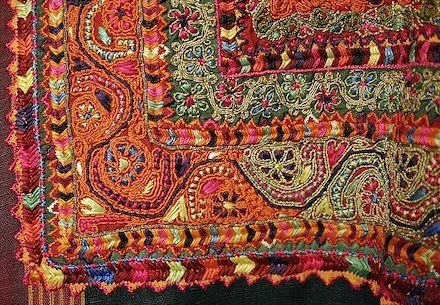

Embroidery from a Bethlehem thobe (ankle-length robe).

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Weaving an Inca textile, Peru. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Rossbach made me consider another aspect of time in art--timelessness. While some art appears meaningful only in its era, other art seems to transcend the period in which it was created. We can view work from centuries ago, or even longer, and recognize something about it that time doesn't erase. Its beauty or message or spirit--its je-ne-sais-quoi quality--is indifferent to time. British writer, broadcaster, and activist Jeanette Winterson (1959- ) notes this in Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery:

If truth is that which lasts, then art has proved truer than any other human endeavour. What is certain is that pictures and poetry and music are not only marks in time but marks through time, of their own time and ours, not antique or historical, but living as they ever did, exuberantly, untired.

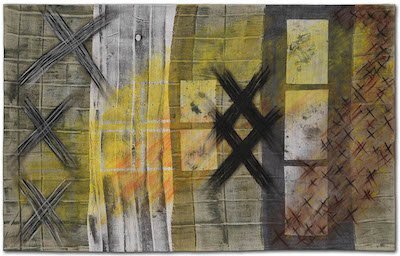

Textile artist Cynthia Corbin's wall hanging "Marking Time" seems to visually capture Winterson's thoughts.

Marking Time, by Cynthia Corbin.

Source: cynthiacorbin.com/index.html

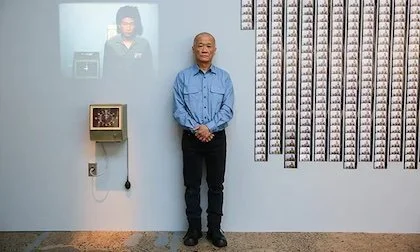

Another way of marking time comes across in "0 to 60", a 2013 show on the concept of time and its artistic manifestations at the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. Two particular conceptual artworks stimulated the curator to formulate this exhibit. Both strike me as conveying a sense of time that is tedious, even grueling. In "Punching the Time Clock," Taiwanese performance artist Tehching Heieh (1950- ) punched a time clock every hour on the hour for a solid year (April 1980-April 1981), never sleeping more than an hour at a time during the entire twelve months. Each time he punched the clock, he also took a single photo of himself, which became a 6-minute video. Part of the performance was shaving his head before the piece began, so that his growing hair would reflect the passage of time. Documentation was originally exhibited at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2009, using film, punch cards, and photographs.

Tehching Hsieh with One Year Performance 1980-1981 at Carriageworks, Sydney, Australia. Photograph: Anna Kucera/The Guardian Photograph: Anna Kucera/The Guardian. Source: theguardian.com/artanddesign/australia-culture-blog/2014/apr/30/

Another artist who marks time in an unusual way is Irish artist John Gerrard (1974- ). Oil Stick Work depicts a grain silo in Kansas being painted at the rate of one square meter a day for thirty years (to be completed in 2038!).

Oil Stick Work, by John Gerrard. Source: johngerrard.net/

And then, of course, there’s British sculptor, photographer, and environmentalist Andy Goldsworthy (1956-). I remember watching Thomas Riedelsheimer's 2001 documentary "Rivers and Tides." Revisiting Goldsworthy now, I see how time is actually the medium in his site-specific land art. I guess I shouldn't have been surprised that, when I looked up the etymology of "time," I learned that it originates from the Old English tid, for tide. I can still visualize one of Goldsworthy’s sculptures gradually succumbing to the tide rolling in. Right there on the beach was the intersection of art and time.

Source: thamesandhudson.com/

Questions & Comments:

How do you think of time? How does it play a role in your creativity?

Which artworks convey a sense of time?

What are the ways in which an artist can represent time?

What artwork has a timeless quality for you?