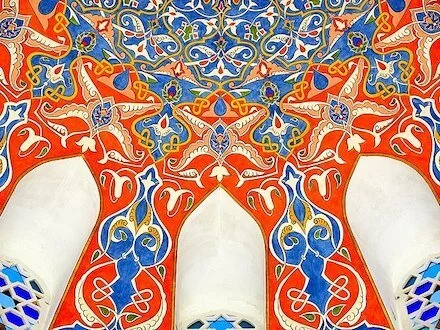

Symmetry and Asymmetry

Ferhat-Pasha mosque arabesque (Banja Luka, Republika Srpska, Bosnia/Herzegovina. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Is symmetry the norm in life and in art? Without looking more closely, we might assume that it is. Symmetry surrounds us in nature and in ourselves. But that’s not the entire picture. Though the body appears bilaterally symmetrical—two ears, two eyes, two arms, two legs, two breasts—it actually isn’t a copycat version on both sides. If you view your eyes in a mirror, do they appear exactly the same? Even the walls of our heart are asymmetrical. And research indicates that we are more likely to consider people attractive when they have slightly asymmetrical facial features. According to a proverb attributed to Egypt, “A beautiful thing (or a thing of beauty) is never perfect.”

Portrait of a man, Delhi, India, by Jorge Royan.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Nor are artworks necessarily a completely even distribution of halves—mirror images on either side of a center line—though many are, especially in earlier centuries. Symmetry may create a sense of harmony and balance as well as convey order rather than chaos, even in complicated patterns (as in the mosque arabesque above), but too much of it can also be undesirable. For some people, perfectly symmetrical compositions or designs may become boring rather than beautiful. Perhaps that’s why I find fukinsei, a Japanese aesthetic principle of asymmetry or irregularity, more appealing. Instead of controlling balance in a composition through regularity and symmetry, dynamic interest is created with just the opposite.

Fine Wind, Clear Weather (Gaifū kaisei), also known as South Wind, Clear Sky or Red Fuji, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji (1830-1832), by Katsushika Hokusai, published by Nishimuraya Yohachi. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Serving container (Mukōzuke), Japan (between 868 and 1912). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

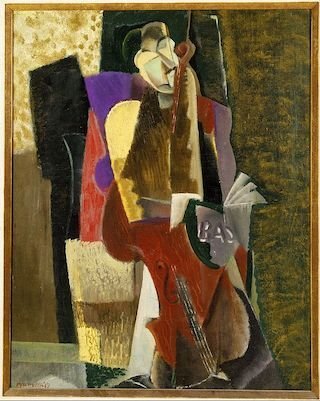

The asymmetry that I admire in East Asian art is not the same as what I notice in cubism and surrealism, in which artists distort the human figure.

The Cellist (1917), by Max Weber.

Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

The Weeping Woman (La Femme qui pleure), 1937, by Pablo Picasso. Tate Modern, London. Source: en.wikipedia.org/

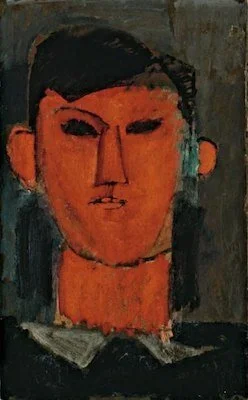

Portrait de Pablo Picasso (c.1915), by Amadeo Modigliani. Private collection. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

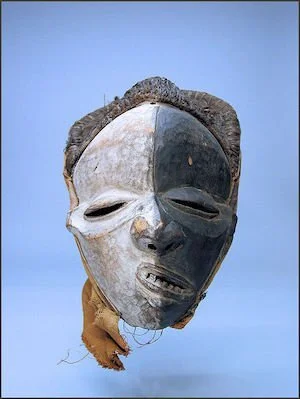

It’s likely that such artists in Europe were inspired by African masks and sculptures on display at the Musée du Trocadéro in Paris. In various indigenous cultures, some masks are asymmetric distortions for a purpose. A recent article by Lincoln Perry in The American Scholar notes that, traditionally, when a respected Pende hunter developed facial paralysis, a mbangu sickness mask was worn as a cure. What we might call a craft or an art object was not created as such but as a healing tool. The distortion or facial asymmetry reflects something is quite amiss.

Pende mbanga mask, southwester Democratic Republic of Congo.

Source: randafricanart.com/

Inuit mask, Greenland. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

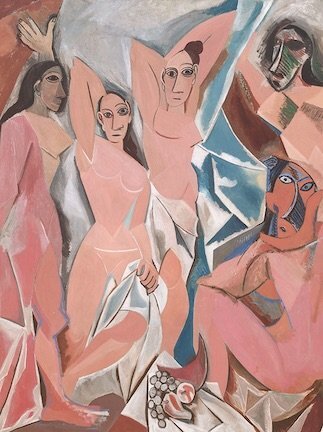

Then Perry points to the influence of masks in the faces of the nude prostitutes in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. [The artist’s attitude toward and treatment of women is for a different discussion.]

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), by Pablo Picasso. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Source: artsy.net/

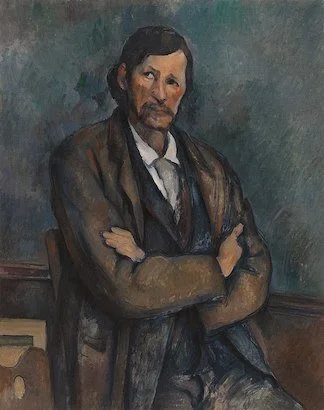

Though they might seem similar, asymmetry and distortion differ, in life and in art. Distortion is defined as “the act of twisting or altering something out of its true, natural, or original state.” It’s no wonder then that distorted faces and bodies might strike us as not only disagreeable, but also as disturbing. This is probably why most people prefer symmetry. On the other hand, asymmetry is simply, and less dauntingly, the “lack of equality or equivalence between parts or aspects of something.” Cézanne’s Man with Crossed Arms is asymmetrical yet not distorted in an unsettling way.

Man with Crossed Arms (c.1899), by Paul Cézanne. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Asymmetry in the arts does not mean a lack of balance. Each half of a composition can be different yet have equal visual weight. Consider the “Cara Grande” mask, which is symmetrical, and then the asymmetrical ikebana floral arrangements. Is there equilibrium in all three objects?

Cara grande (“large face”) mask, by the Tapirapé people in Mato Grosso State, Brazil. Museum of the American Indian, the Smithsonian, Washington, D.C.

Source: americanindian.si.edu/collections

Ikebana flower arrangement from the Kadō Kōya-san at the Nagoya Ikebana Art Exhibition, Citizens' Gallery Sakae, Nagoya, Japan (November 2018). Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Ikebana flower arrangement from the Kadō Kōya-san at the Nagoya Ikebana Art Exhibition, Citizens' Gallery Sakae, Nagoya, Japan (November 2018). Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

As you look at paintings, sculptures, fiber art, ceramics, and even people, here’s a question you might ask: Am I seeing symmetry or asymmetry? What makes it so? Which do I consider more attractive, and why? So often, I have an immediate and unconscious preference for what I’m seeing. Now I’m going to probe whether that’s because, beyond the colors, images, or patterns, I sense balance symmetrically or asymmetrically.

Bound (2007), tapestry by Alex(andra) Friedman. Source: textilecurator.com/

And as I observe my environment, I’m going to take in how Nature creates that balance too.

Poertschach Landspitz Eiche im Herbstkleid, Carinthia, Austria. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Questions & Comments:

Which appeals to you more, symmetry or asymmetry? How do you explain your preference?

What favorite artworks most represent for you these two kinds of balance?

As an artist, how do you achieve balance through symmetry or asymmetry in your own work?