Indigenous Creativity with Fiber

During a recent visit to Denver (my first trip since the onset of Covid), I went to the Denver Art Museum (DAM) twice, where an extensive exhibit of Indigenous arts caught my attention. It confirmed for me, yet again, that abstraction has been integral to native peoples’ creative expressions since long, long before it ever appeared in the Western modern canon. But, as with women’s handiwork—quilts come to mind—they were, with enormous hubris, relegated to a category called domestic crafts, in the case of women, and collectible archeological resources, in the case of tribal groups. About all that, there is much interesting and provocative discussion that is worth reading. However, in this post, I want to share with you some of the many fiber pieces I viewed. Although DAM has 18,000 plus diverse objects by artists from more than 250 Indigenous nations, I am particularly fascinated by the ingenuity and ability of people around the world to extract fibers from the plant kingdom to create things not only of beauty but also of functionality and practicality.

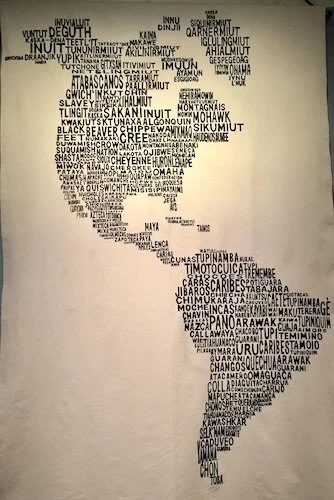

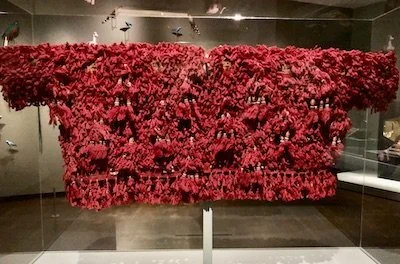

Pueblos originarios del continente [Original peoples of the continent] (2020), by Carla Fernández and Pedro Reyes; hand embroidered by Otomī artisans Endy López, Tericila Santiago, Dulce Pérez, Roxana Pérez, and Nayeli Juárez.

I invite you to take a brief walk with me through part of the DAM, one of the first art museums in the country to collect Indigenous arts from North America. While other institutions considered them anthropological material, since the 1920s DAM has recognized and valued their fine aesthetic qualities. The museum also includes the work of contemporary Native artists.

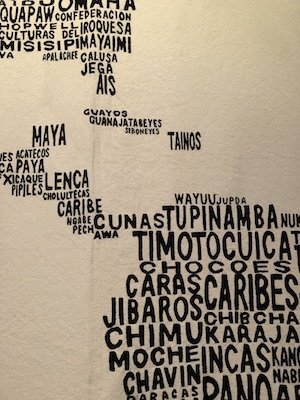

Detail of Pueblos originarios del continente [Original peoples of the continent] (2020), by Carla Fernández and Pedro Reyes

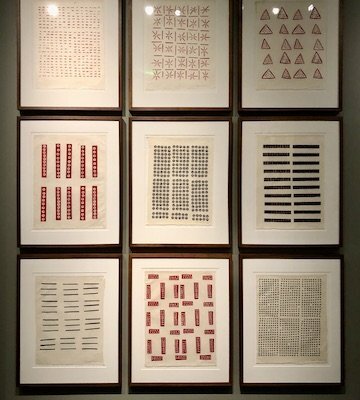

According to the DAM, Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë resides in a remote Yanomami community in the Venezuelan Amazon near the border with Brazil. In these monotype prints of oil-based ink on Hanji mulberry paper, we see a group of abstract designs that combine elements of Yanomami visual culture—e.g., patterns on baskets and body art—with his own motifs that represent animals living along the Orinoco River, the source of life for his people.

Top row from left: tipikirimi; kashihiwe; kohorarawe

Middle row from left: uwauwami; hisiriki; tipikirimi

Bottom row from left: pariki husepari; kashausi; shaririwe Il, by Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë (2019).

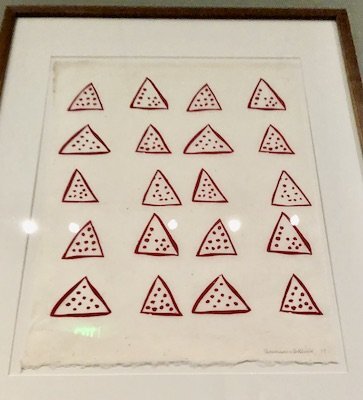

From the top row: kohorarawe (2019),

by Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë.

Tasseled tunic (900-1400), by unknown Chimú artist, Peru.

Cotton and camelid fiber.

Detail of tasseled tunic (900-1400), by unknown Chimú artist, Peru. Cotton and camelid fiber.

The Inka [Inca] employed khipus, a system of knotted cords, as a portable record of the movement of goods and people across their vast empire. Khipus served as accounting ledgers as well as devices to remember stories. When the Spanish eradicated the use of the khipu, the specialized knowledge necessary for understanding it also disappeared.

Khipu (around 1434-1533), by Khipucamayoc [Khipu maker], Cuzco, Peru. Camelid fiber.

In the Chilkat (Naaxein) blanket below, a Tlingit weaver of Southeastern Alaska used dyed yarn made of mountain goat wool twisted around a cedar bark core for the vertical strands of the warp and mountain goat wool for the horizontal strands of the weft.

Chilkat (Naaxein) blanket (mid-1800s), by a Tlingit artist. Dyed mountain goat wool and cedar bark.

This open work headpiece (k'ise:qot) is made from iris fibers. It is decorated with feathers that trail down the wearer's back. Such a headdress is part of the important White Deerskin Dance in World Renewal ceremonies. Typically, it is worn beneath a sea lion-tusk headband by the ceremony's most important male dancers, known as obsidian bearers because they carry sacred obsidian blades.

Headdress (1900), by Hupa (Athabaskan) artist. Iris fiber, feathers, and animal hide.

Headdress (1900), by Hupa (Athabaskan) artist.

Long before others began using cotton, by 700 CE, the Puebloan people (sometimes called Anasazi by archaeologists) were growing the plant in New Mexico. The mantas (shawls) shown here on the left include some of the earliest complete Acoma textiles. Artists at Acoma Pueblo weave a variety of white and black mantas (shawls), sometimes with colorful embroidery along the top and bottom borders in sophisticated designs. Blankets on the right were traded by their Navajo makers to Ute and Shoshone tribes who, in turn, traded them to high-ranking families from tribes on the Plains and Plateau. This is how they became known as hanoolchaadi or Chief's blanket.

Four Acoma mantas (shawls) on the left; wool or wool and cotton; from about 1860 to 1910. Navajo First-, Second-, and Third-Phase Chief’s blankets on the right; dyed and undyed wool; from the 1820s to about 1870.

Detail of Acoma manta.

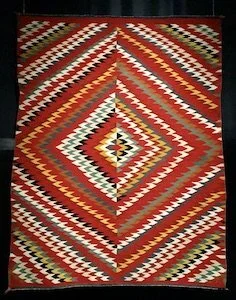

Before op art sprang up in Europe, there were the bold and complex designs of Navajo “eyedazzlers” (dah’iistt'ó).

Dah’iistt'ó (Eyedazzler), by a Navajo artist, about 1885; dyed wool/cotton.

Detail of dah’iistt'ó (eyedazzler), by a Navajo artist, about 1885.

Dah’iistt'ó (Eyedazzler), by a Navajo artist, about 1890; dyed wool and cotton.

I had never heard of stitching with moosehair before I stood before this tablecloth. Huron-Wendat women were so prized for their moosehair embroidery that the French considered their work superior to the best European embroidery being made in the 1600s to 1800s. Fewer than 10 moosehair tablecloths of this scale, like the one below, are known to exist.

Embroidered tablecloth (mid-1800s), by Wendat artist, Wendake, Quebec. Wool and moosehair.

Detail of embroidered tablecloth (mid-1800s), by Wendat artist, Wendake, Quebec.

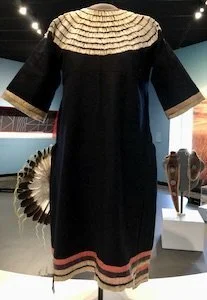

And, of course, clothing and accessories.

Girl's dress (late 1800s), by Apsáalooke (Crow) artist. Cloth, bone, elk teeth, hide, string, dye.

Dress (1800s), by Ochéthi Sakówin (Sioux) artist. Cloth and dentalium shell.

In the Andean regions, such as Peru and Bolivia, the fiber was hair shorn from camelid animals (llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos). When the Spanish colonized the continent, they introduced sheep, providing wool as an alternative. Cotton was cultivated at lower elevations.

Four-cornered hat (800-1000 CE), by unknown Wari artist, Central coast of Peru.

Knotted camelid fiber.

Detail of four-cornered hat (800-1000 CE), by a Wari artist.

Bag with silver plaques (1300-1400 CE), North Coast, Peru. Cotton, camelid fiber, cochineal dye, silver, shell beads.

Coca bag (200-600 CE), by unknown Nasca artist, South Coast, Peru.

Camelid fiber.

Detail of coca bag (200-600 CE), by a Nasca artist.

While the Denver Art Museum has many more objects of fiber from other parts of the world, it would be too much to incorporate all of them here. The Americas alone have a great deal to say about fiber art and abstract design. Contemporary work carries on evolving traditions while also making statements about today’s issues. But they’re for another post.

I’ll end with this last image, one of two Pueblo vessels—no, not made of plant fiber but of clay—because of the striking geometric patterns. Indigenous arts have always been way ahead of movements in the West thought of as avant-garde. But more than that, as Inupiaq artist Sonya Kelleher-Combs says in a video at DAM, “Our objects are…incised with beautiful motifs and patterns to strengthen or give power to an object. [They] are imbued with history…and a connection to community.”

Questions and Comments:

What indigenous arts have influenced your artwork?

What is it about them that inspires you?

Do you make a distinction between Indigenous arts and so-called fine art? If you do, how would you describe that?