Big Fiber/Small Fiber: Ursula von Rydingsvard’s Contours of Feeling

When I was in Colorado in May, a friend graciously invited me to meet her at the Denver Botanical Gardens, where she is a member. I didn’t anticipate how much art I would be viewing: not only the spectacular plant life as we walked through the grounds and tropical house, but also the kind of art one can make with natural fiber. Some of the flora even suggested ideas for fiber art.

I don’t know the name of the plant below, but I was drawn to it because it stimulates my imagination for mark making on textiles and paper with thread or ink. The leaves’ variegation could even be asemic writing.

I don’t design textiles, but this lacebark pine from China challenges me to come up with a green, gray, black, and pink pattern. Because of the plaques of color, I also see collage possibilities with paper or fabric.

And, in this tree, the pink blossoms look like huge French knots emerging from the bark!

Then, once inside the gallery, I had the unexpected opportunity to experience Ursula von Rydingsvard’s exhibition of outsized abstract cedar sculptures and delicate pieces created with other organic materials. It was definitely an instance of synchronicity because, not long before, I had watched a series of videos on women artists and one of them was about Ursula von Rydingsvard. I hadn’t remembered her name, only how mammoth her works are. That’s why, until I stepped into the gallery, I had no idea that I was going to have an in-person view to flesh out the on-screen observation. No matter how good a video or photograph is, there’s no comparison—especially when it comes to size and texture—with being right there, standing in front of or walking around the artwork. This is particularly true for von Rydingsvard’s massive pieces. Despite their monumental dimensions, there is also an intimacy to them because each cut in the wood, each shaping of the cedar, reflects the presence of hands. [For a more immediate sense of the artist and how she works, see the short videos at the end of this post.]

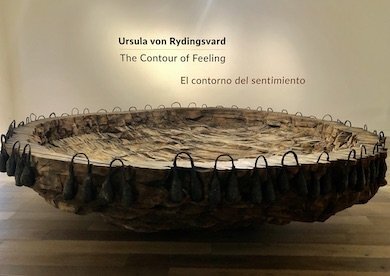

Ocean Floor (1996), by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

Cedar, graphite, cow intestines.

Ursula von Rydingsvard: The Contour of Feeling was organized by The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia and guest curator Mark Rosenthal, former curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The title of the exhibition is taken from a line by the Austrian poet Rainer Marie Rilke (1875-1926), von Rydingsvard’s favorite: “We don’t know the contour of feeling, we only know what molds it.” Although the titles of her works do not indicate the feelings behind them, I suspect the artist is drawing on some difficult memories from her early childhood and perhaps from later on as well. However, she prefers that viewers come up with their own interpretation rather than expect it from a title. Von Rydingsvard says that her titles in no way explain the pieces because words cannot accurately describe the emotions that inform her urge to create.

Detail of Ocean Floor (1996), by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

Cedar, graphite, cow intestines.

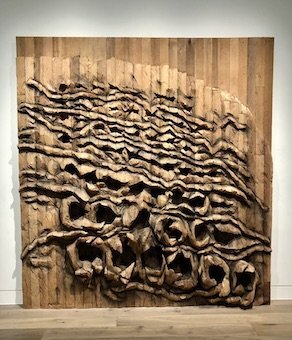

Despite her admonition, I can’t help but think that the title Zakopane refers to a resort town in southern Poland, at the base of the Tatras Mountains, popular for both winter sports and summer mountain climbing. It is also known for its old wooden chalets, symbols of Zakopane-style architecture.

Ocean Floor in front of Zakopane (1987),

by Ursula von Rydingsvard. Cedar, paint.

Detail of Zakopane (1987), by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

Although von Rydingsvard was born (1942) in Deensen, Germany, her parents were Polish and Ukrainian, from a long line of peasant farmers. Her father worked as a forced laborer under the Nazis during World War II. Afterward, the family lived in nine different displacement camps for Polish refugees in Germany. They emigrated from Europe at the end of 1950 and took up residence in Plainville, Connecticut. Von Rydingsvard does not consider her sculptures as directly autobiographical, but they are imbued with her life experiences. I can imagine her as a very young girl during and after the war, not yet able to make sense of what was happening; nonetheless, a range of feelings and memories registered in her body.

Collar with Dots (2008), by Ursula von Rydingsvard. Cedar, pigment.

Collar with Dots (2008), by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

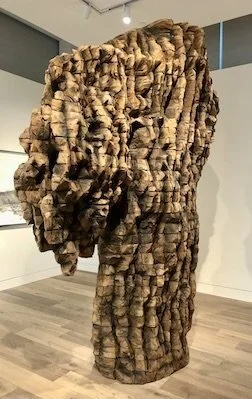

To get a sense of the scale at which von Rydingsvard sculpts, For Natasha (below) stands 9 ft. 1 in. x 6 ft. 7 in. x 3 ft. 6 in. Her outdoor installations are often twice that size.

For Natasha (2015), by Ursula von Rydingsvard. Cedar, graphite.

So how does a not hefty woman manage such daunting structures? Small parts grow into something gargantuan, and von Rydingsvard works with a team of assistants. First, she imports the wood in four-by-four beams from a mill in Vancouver to her studio in Brooklyn, New York. Before working with it, she draws a chalk outline of a base on the floor, moving intuitively and making adjustments along the way. “The worst thing is for me to try to figure out exactly and specifically what the sculpture needs to look like,” von Rydingsvard has said. Then her team stacks 4” x 4” cedar boards, which she marks to indicate where details are to be carved. Based on these lines, she and her assistants use circular saws to shape each piece. With extra-strength adhesives, they glue the layers together.

Ursula von Rydingsvard applies graphite through perforated plastic on For Staś (2011–17); © Ursula von Rydingsvard, Courtesy of Galerie Lelong & Co.;

Photo by Morgan Daly. Source: https://nmwa.org/blog/artist-spotlight/finding-meaning-in-form-ursula-von-rydingsvards-process/

This is not work for the fainthearted. Everyone wears protective masks and suits because of the dangerous equipment, blowing sawdust, and toxic fumes. Sections of each piece are carefully numbered and screwed together. The last step in the process is rubbing the wood with pigment or graphite to bring more details to the surface. This intensive labor can take a year or more for a single sculpture. Even when von Rydingsvard makes one in bronze or copper, she first renders it full-sized in cedar in order to retain the kind of textural quality that is essential to her aesthetic. The result is that every square inch has been manipulated.

Thread Terror (2016), by Ursula von Rydingsvard. Cedar, graphite.

Detail of Thread Terror (2016),

by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

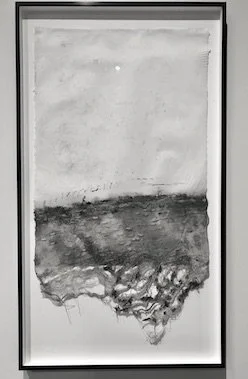

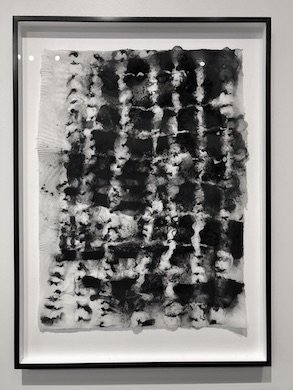

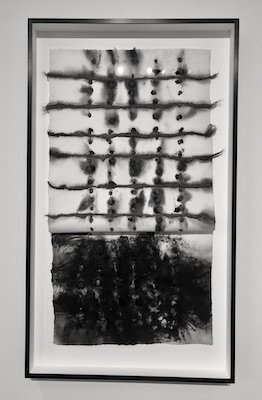

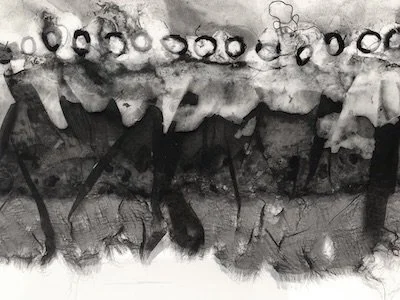

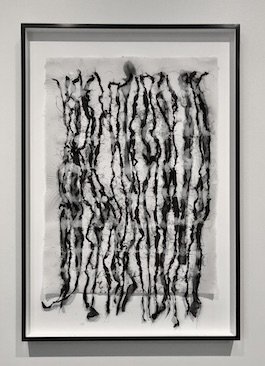

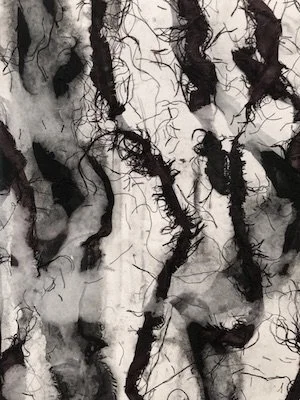

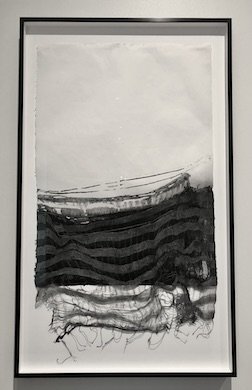

Having watched a video about von Rydingsvard, I certainly didn’t expect to see anything but the exceptionally heavy wood sculptures. I was pleasantly amazed to encounter a whole other side to her creativity. On a wall opposite the large works hung a series of lightweight fragile works on paper that she started in 2009 during a residency at Dieu Donné, a non-profit cultural institution in Brooklyn dedicated to art using hand papermaking. In the pieces below, von Rydingsvard incorporates pigments, fibers, and personal objects into wet paper pulp. In terms of process, this practice seems in stark contrast to the laborious one demanded by the massive works. It allows her, as the curator notes, “to explore immediate, gestural ideas.” I understand the appeal. It used to take me years to complete a book, but with fiber art there is the possibility of fulfillment so much sooner.

The pieces below are from 2016-17. All are linen handmade paper with mixed media. From a distance, some of them evoke, for me, a feeling of landscape and seascape.

Artwork by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Detail of work immediately above by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Artwork by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Detail of work immediately above by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

Artwork by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Detail of work immediately above by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

Artwork by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Detail of work immediately above by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Artwork by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Detail of work immediately above by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

Artwork by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Detail of work immediately above by

Ursula von Rydingsvard

Artwork by Ursula von Rydingsvard

Detail of work immediately above by

Ursula von Rydingsvard.

There are other works in the exhibition that have similarities to and differences from all the images so far. Perhaps Book with No Words is a statement about not having the literal vocabulary to describe her interior states, though from things von Rydingsvard has said, her entire oeuvre is an expression of what’s hard to describe yet must get externalized in some way.

Book with no words I (2018), by Ursula von Rydingsvard. Cedar, linen.

And what might the artist be alluding to with Ten Plates, the large family she comes from?

Ten Plates (2008-11), by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

Cedar, plaster, and mixed media.

Nor do I know what von Rydingsvard intends with the title Krasawica, so I looked it up. I thought that, like Zakopane, it might be a place in Poland, but it seems to be borrowed from the Russian краса́вица (krasávica), which translates as “a beauty” or “beautiful.”

Krasawica II (1998-2001), by Ursula von Rydingsvard.

Cedar, graphite.

While there are more works in the exhibition, I’ll close with the last thing(s) I looked at and her statement about why she makes art. In the image below is her ever-growing assemblage of what she calls “little nothings.” They adorn the walls of her studio, a space which is her sanctuary. There are miscellaneous tools, cedar objects, copper wires, photographs, lace, threads, and drawings on paper. According to the curator, these represent the artist’s admiration for the “humble.” Some are discoveries that she will explore further and in which she might find inspiration for colossal pieces.

Little Nothings (2000-15), by Ursula von Rydingsvard. Various materials.

On one whole wall I read why von Rydingsvard makes art:

Mostly, to survive.

To survive living and all of its implied layers.

To ease my high anxiety, to numb myself with the labor and the focus of building my work.

Objects or the process by which I concretize my ideas feels so good.

…intense anxiety moments from which I have to unravel myself.

Because there’s a pleasure in it.

Because there’s pain in it.

Because I endure a hefty load of self-doubt.

Because I have confidence in the possibility of seeing this work through.

Because I see life as being full of abominations.

Because life is full of marvels close to miracles.

Because I still don’t get who I am.

Because I will never get who I am.

Because my deepest admiration goes to those who have made art that has interested me.

Because I want attention from those who make good art.

Because I need to use both my body and mind. The labor of my body is what keeps me awake and alive…what numbs me and offers a kind of veneer between me and the things in life which are painful to face.

Because the visuals—that which I perceive through my eyes—are an extraordinarily important part of my life.

Because I don’t want to be doing anything else with my life…the building of my art work feels like the most consequential thing I could be doing with my time.

Because I can run into a world of my making, both physically and mentally.

Because I like working with a group of assistants who become another kind of family.

Because I like the daily rhythm of going to my studio.

Because it’s a place to put my pain, my sadness.

Because there’s a constant hope inside of me that this process will heal me, my family, and the world.

Because it helps fight my inertia.

Because I like embroidering around my long-ago Polish fantasies.

Because I can reach into the future with my work.

Because I constantly need to try to better understand the immense suffering and pain of my family that I never seem to be able to really understand.

And also, because I want to get answers to questions for which I know there are no answers.

Questions & Comments:

If you have seen von Rydingsvard’s works, what impression did they make? What do you think she’s expressing through them?

Do you sense a disjunct between the hefty sculptures and the delicate fiber pieces in frames or are they two sides of one coin?

If you work large, how do you manage it?