What Does a Portrait Tell Us?

The Mona Lisa or La Gioconda (1503-1505), by Leonardo da Vinci. Louvre Museum, Paris. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Today, with a selfie feature on cell phones, a single touch makes creating a portrait of yourself easy and simple. Plus you can keep clicking until you get just the right look you want. But this was definitely not always so. Portraits have been around for a very long time, maybe for as long as 27,000 years. Whether painted, sculpted, carved, or built with clay, creating them took patience and effort, one at a time. In representing someone with paint, stone, metal or wood, and now with textiles and recycled objects, an artist generally is aiming for some kind of likeness, be it realistic or idealistic. More than a physical resemblance, does the portrait also give us a sense of the individual’s personality or a particular mood, and how does one capture that? Beyond any personal aspects, what does the portrait convey politically, historically, spiritually, socially? What do we learn about the place and time in which it’s set, the disparity between classes and ethnic groups? A portrait is not just a beautiful or handsome face. It can reveal aspects of society.

Plastered skull, Tell es-Sultan, Jericho, Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, circa 9000 BCE. Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Source: en.wikipedia.org/

Moche ceramic portrait vessel (100–800 C.E.), north coast Peru. Fowler Museum, University of California, Los Angeles. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Traditionally, portraits recorded the appearance of people who held power, wealth, and royal/aristocratic titles. The images could reflect that person’s dominance, comeliness, even virtue or learning. Portrait artists were expected to execute flattering images of the patrons who commissioned the work. Take Bernhard Strigel (1460-1528), a German painter in favor with Emperor Maximilian I and for whom he repeatedly journeyed to Augsburg, Innsbruck, and Vienna.

Emperor Maximilian I and his extended Hapsburg family (after 1515), by Bernhard Strigel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Art historians have revealed that some paintings, formerly attributed to men, were actually rendered by women, often in the same family. Artemisia Lomi Gentilischi (1593–c. 1656) may have been one of them. Recognized for her talents in her teens, she became known for her ability to depict the female figure with great naturalism and to handle color skillfully in demonstrating dimension and drama. Today, she is considered one of the most progressive and expressive painters of her generation, when women were seriously hampered by legal and social restrictions to owning property and running their own affairs, not to mention limited freedom of movement.

Does the portrait of the woman below reflect a contemplative mood, composure or concern, possibly confidence in her station in life? That she could afford such a sumptuous outfit certainly indicates wealth, though it was likely to be her family’s or husband’s.

Portrait of a seated lady, possibly Caterina Savelli, Principessa di Albano, in gold-embroidered dress (c.1625), by Artemisia Gentileschi. Private collection. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

Long before selfies came into vogue, artists also created self-portraits. German painter, printmaker, and theorist of the German Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) did a silver point drawing of himself as early as the age of thirteen.

Self-portrait at Thirteen (1484), by Albrecht Dürer. Albertina Museum, Vienna. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-69) is reputed to have created a kind of visual autobiography with some 80 self-portraits. Having experienced personal and financial losses through the decades of his life, perhaps those self-portraits tell us something about how he felt during those unfortunate times. In the one painted only nine years prior to dying, is he sad, resigned, or philosophical about how things turned out?

Self-portrait (1660), by Rembrandt. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

When she was still a young woman, Italian Renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1532-1625) was able to travel to Rome and meet Michelangelo, who immediately recognized her talent. She later became an official court painter to the Spanish king, Philip II. Although known for such portraits as well as religious paintings, I find her self-portraits and depictions of her family more appealing. I admire how much she was able to achieve despite the limitations placed on women in her time. As young as she appears, she comes across as clear-eyed, capable, and self-assured in front of a painting on her easel.

Self-portrait at the easel (1556), by Sofonisba Anguissola. Łańcut Castle, Poland. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Over time, portraits were no longer confined to the rich and famous and also became more impressionistic than realistically detailed. Like Rembrandt, Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-90) created many self-portraits in his short life—36 in the span of only ten years. While they represent him as having red hair, green eyes and an angular face, each face shows us something different. Van Gogh wrote: People say–and I’m quite willing to believe it–that it’s difficult to know oneself–but it’s not easy to paint oneself either. In none of them is he smiling; his visage is serious, maybe even grim. In the self-portrait painted a year before his untimely death, what is he thinking about? Does he sense the end is near? Is he finally satisfied with his oeuvre? Does he have any regrets or is he accepting? And does his injured ear still hurt?

Self-portrait with bandaged ear and pipe (1889), by Vincent van Gogh. Kunsthaus Zürich, Switzerland. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Of her 143 paintings, 55 are self-portraits of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907-54). Filled with physical and emotional pain and a turbulent marriage to fellow artist Diego Rivera (1886-1957), she became an important subject of her artwork. As she said: I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.

Self-Portrait with Monkeys (1943), by Frida Kahlo.

Museo delle Culture di Milano, Milan. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Some portraits, painted or sculpted by men and women of dominant white society, portray people of color or of other cultures, as exotic and even sexualized.

Woman of Algiers (Odalisque) (1870), by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Through a note in one of French artist Édouard Manet’s (1832-83) notebooks, the model for his painting La Négresse was identified as Laure, a young woman of Antilles origin, who lived close to his Paris studio. Rather than exoticism, Manet may have been referencing the end of slavery in France, abolished in 1848. Laure may also have been the model for the maid holding a bunch of flowers in Olympia (1863-65).

La Négresse (1862), by Édouard Manet. Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli Gallery, Turin, Italy. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

It’s hard not to notice the difference in the women’s expressions in these two paintings and the sculpture by French artist Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-75). Can we ever know what these women were truly thinking and feeling, though their eyes and mouths seem to talk to us?

La Négresse, by Abigail May Alcott Nieriker. 1879 Paris Salon. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

La Négresse (1872), Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

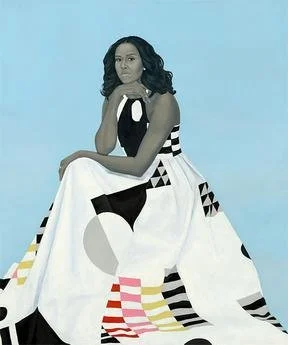

Do you sense a difference in portraits painted instead by African-American artists?

First Lady Michelle Obama (2018), by Amy Sherald. National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. Source: en.wikipedia.org/

President Barack Obama (2018), by Kehinde Wiley. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Source: en.wikipedia.org/

Some artists, such as American painter Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) add a soft touch in portraying the everyday lives of women and children rather than the careers of kings and generals. American visual artist Alice Neel (1900-84) depicts friends, family, lovers, poets, artists, and strangers of different ethnicities and socio-economic groups.

Young Mother Sewing (1900), by Mary Cassatt. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

Blanche Angel Pregnant (1937), by Alice Neel. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/

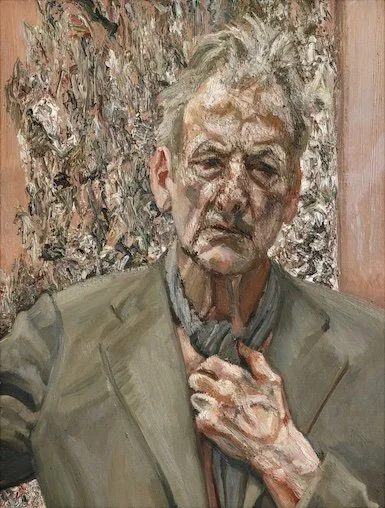

And there are artists, such as Lucian Freud and Alice Neel who, like Rembrandt, don’t balk at showing every wart and wrinkle of their aging body in a self-portrait.

Self-Portrait (Reflection) (2002), when Lucian Freud was 80 years old. Art work © The Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman Images. Source: newyorker.com

Self-Portrait (1980), by Alice Neel. © The Estate of Alice Neel. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Source: npg.si.edu/

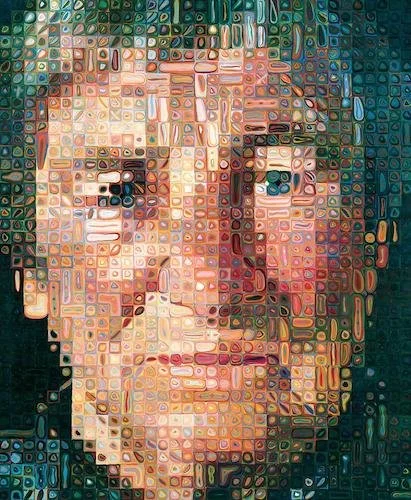

There are so many ways and so many materials with which to create portraits. Despite his disabilities, American artist Chuck Close (1940-2021) made massive-scale photorealist and abstract portraits of himself and others with grids of tiny squares of paint that, when viewed all together, become a face.

Agnes (1998), a portrait of Canadian artist Agnes Martin (by Chuck Close. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

©Estate of Chuck Close. Source: sfmoma.org/

Other artists make portraits with fabric scraps, buttons, zippers, and all kinds of other recycled objects (bottle caps, plastic bags, cables, etc.), as you can see in this brief video. There’s no end to the creative resourcefulness of artists from the earliest times till today. So how would you like to be portrayed? What would you want your portrait to tell us?