Chaos and Art

The word "chaos" is unlikely to be a stranger to any of us. All we have to do is read or listen to the latest news, not to mention the dramas that occur in our families and workplaces. Chaos is everywhere and, too often, destructive. This past winter in northern California was certainly proof of climate chaos as we experienced what meteorologists called “atmospheric rivers.” They resulted not only in severe flooding, but also in hundred upon hundreds of trees falling onto roads, streets, cars, and houses.

Yet, there is also a creative side to chaos. Webster's defines chaos as "the confused unorganized state of primordial matter before the creation of distinct forms; a state of utter confusion." It makes sense to me that artists can create something out of chaos. But I was surprised by the opposite.

Credit: NASA HST / CXC / MAGELLAN. Source: pbs.org/newshour/science/primordial-black-holes-could-explain-dark-matter-galaxy-growth-and-more

Quite a number of years ago, I read two collections of interviews with artists in which the word “chaos” popped up several times: Edouard Roditi's Dialogues: Conversations with European Artists at Mid-Century (1990) and Cindy Nemser's ART TALK: Conversations with 15 Women Artists (1975/1995). In her discussion with German-born American sculptor Eva Hesse (1936-1970), Nemser mentions Morse Peckham's book, Man's Rage for Chaos (1967). Its central premise is that art does not unify and order experience. Instead, art is an area where we involve ourselves in chaos. In this way, art breaks up one's ordinary orientation by frustrating and weakening a tyrannical drive to order. Whether or not I agree with this perspective, I am curious as to how artists look at their own work and the work of their fellow artists, past and present. Do they see themselves as creating order out of chaos or creating chaos to disturb and disorient?

Addendum (1967), by Eva Hesse, Tate Liverpool, England. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

Nemser says to Hesse: "Art basicaIly makes people aware of the chaos that surrounds them so that they become alive to it." In response, Hesse, who pioneered working with plastics, latex, and fiberglass, points out that this order-chaos relationship can move in two directions:

When Van Gogh first did his paintings, that was fantastic chaos. Now it's so conventional. Jackson Pollack showed us that. What is more chaotic than those drips, but he made his order out of that, so it was the most ordered painting.

Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (Arles, 1888), by Vincent van Gogh. Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

Lavender Mist (1950), by Jackson Pollock. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

In a 1958 conversation with Roditi, Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), a Czech-Austrian painter, poet, and playwright, expressed his understanding of art and chaos:

The world of experience, as it is revealed to our senses and our understanding, is always chaotic. Each one of us must seek to organize so many conflicting facts, impressions or sensations in some kind of understandable synthesis...which will allow one to face the world as an individual, without being overwhelmed by the kaleidoscopic flow and swirl of phenomena...It is the task of the artist to organize the chaos of the visible world in patterns from which some meaning can emerge.

Portrait of a Woman Facing Left (1923), by Oskar Kokoschka, Botero Museum, Bogotá, Colombia. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

Art has certainly depicted chaos, for there’s enough of it in history: environmental catastrophes and wars are easy examples. I think of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), which conveys the suffering wrought by violence and chaos, or Anselm Kiefer’s Burning Rods (1984-87), which refers to nuclear power plants, such as the one at Chernobyl that cataclysmically failed in 1986.

The Last Day of Pompeii (1830-33), by Karl Brullov. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

The Battle of Onin During the Onin War (1467-1477), by Utagawa Yoshitora, created between 1847 and 1852. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

Burning Rods (1984-87), by Anselm Kiefer. Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, Missouri. Source: mlkemperartmuseum.wordpress.com/2013/08/02/

Guernica (1937), by Pablo Picasso. Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain. Source: en.wikipedia.org/.

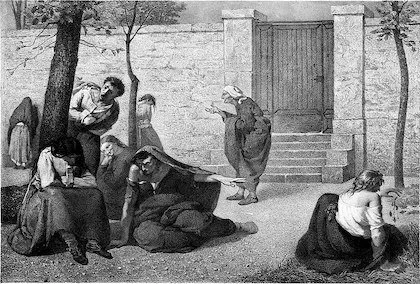

And, of course, there are evocative portrayals of personal chaos, such as The Scream, by Norwegian expressionist painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944), or the lithograph representing various mental conditions in the gardens of the Hospice de la Salpêtrière in Paris.

Folles de la Salpétrière (1857), by Armand Gautier. Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, New Haven, Connecticut. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

Still, I don't recall ever reflecting on the role of art as either creating order or unleashing chaos, though some artwork feels chaotic to me. When I stop to consider what I'm generally drawn to, it's art that imparts a quality of serenity or quiet beauty. It’s art that reveals how space is as important as form and that depicts light as a powerful force, but not in a glaring way. I'm attracted to a certain elegant simplicity, economic rather than highly ornate expression. A few brush strokes on paper or cloth can portray so much more than what is actually painted. This is probably why I'm attracted to East Asian aesthetics, though I can also perceive this sensibility in artists of other cultures. It’s not that I don’t appreciate many kinds of artwork and what I can learn from them—I do—but we all have our preferences.

Plum Branch, Korean hanging scroll (1888), by Yi Yu-won. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

I've pondered why I prefer this kind of art. Maybe because of internal chaos, I seek art which provides calm. Maybe because I get stirred up by ongoing and changing experiences of people, places, and events (Kokoschka's "kaleidoscopic flow and swirl of phenomena"), I don't feel a need for art to engage me in yet more chaos.

Blue #4 (circa 1916), by Georgia O'Keeffe. Brooklyn Museum, New York. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

I often find theories narrow when they assert "this rather than that" or "that rather than this." Just more dualities to deal with. Although we all have certain basic needs, needs differ during different moments. At times, some people need to be jolted awake with a shot of cognitive dissonance while others need to smooth out with art that inspires harmony. Maybe there are eras in which art needs to play a role in breaking up conformity and complaisance, but that doesn't mean it can't also be instrumental in fostering peacefulness. It doesn't have to be only one or the other.

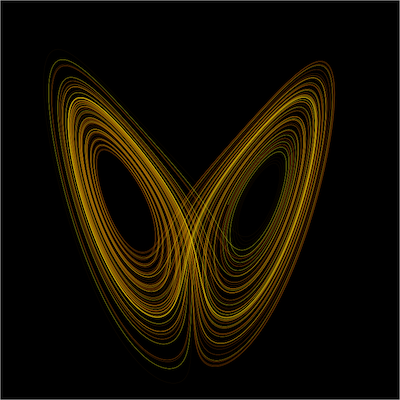

An icon of chaos theory—the Lorenz attractor. Credits: images Lorenz system r28 s10 b2-6666.png by Wikimol and Lorenz attractor.svg by Dschwen. Source: en.wikipedia.org/.

And then there’s chaos theory: Even within the randomness of chaotic complex systems, it is possible to discern “underlying patterns, interconnection, constant feedback loops, repetition, self-similarity, fractals, and self-organization.” So perhaps there’s no true chaos after all, or chaotic art either, only artists who lead chaotic lives.

Fractal patterns of Romanesco broccoli. Photo by Ivar Leidus. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/.

Questions & Comments:

As an artist or art beholder, do you think the role of art is to create order out of chaos or to create chaos or neither?

What effect do you prefer art to have on you?

What effect do you want your art to have on viewers?