Lenore Tawney: Interweaving Creative Process and Spiritual Practice

Before the pandemic, when traveling was still an easy option, I gave a presentation and a 2-day workshop for the North Suburban NeedleArts Guild, a delightful group in the greater Chicago area. The day after I flew in, I enjoyed the privilege of being picked up by one of the members, who graciously took me to the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Since I rarely get to that part of the country, this was an excellent opportunity to visit the four-part retrospective Lenore Tawney: Mirror of the Universe (October 2019-March 2020), curated by JMKAC’s (now former) senior curator Karen Patterson. I knew Tawney was a pioneering fiber artist, but I was unaware of the breadth of her oeuvre and the personal story behind her creativity. The more I learned, the more interested I became.

Portrait of Lenore Tawney (1959) by Yousuf Karsh. ©Yousuf Karsh. Source: karsh.org/lenore-tawney/

Could anyone have predicted her trajectory as an artist? She was born Leonora Agnes Gallagher, in 1907, in Lorain, Ohio, and headed for Chicago twenty years later. During the day, she worked as a proofreader; at night, she took classes at the Art Institute. She married George Tawney, a psychologist, in 1941, but he died six months before they could celebrate their second anniversary. She then moved to Urbana to be close to his family, and studied art therapy at the University of Illinois. In 1946, Tawney began attending the Chicago Institute of Design (now the Illinois Institute of Technology). She studied drawing with Hungarian painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946), sculpture with Ukrainian cubist sculptor Alexander Archipenko (1887-1964), painting with American abstract expressionist painter Emerson Woelffer (1914-2003), and weaving with German textile designer Marli Ehrman (1904-1982). Her training there proved to be an initiation into Bauhaus principles and the artistic avant-garde.

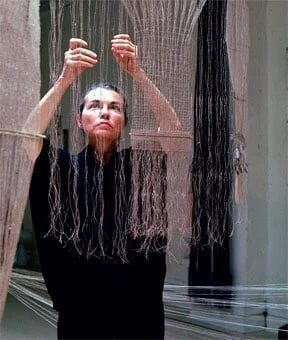

Lenore Tawney. Photo by David Attie, courtesy Lenore G. Tawney Foundation. Source: magazine.artland.com/lost-and-found-artist-series-lenore-tawney/

Tawney resided in Paris from 1949 to 1951; from there, she traveled widely throughout North Africa and Europe. Once back in the States, she also studied with Finnish weaver Martta Taipale at Penland School of Crafts. But it was her decision, at the age of 50, to leave a very comfortable life in Chicago that dramatically furthered her artistic journey. She opted for “a barer life, closer to reality, without all the things that clutter and fill our lives. The truest thing in my life was my work,” she said. “I wanted my life to be as true. I almost gave up my life for my work, seeking a life of the spirit.” She drove to New York and moved into a large loft studio in Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan, where her neighbors were artists Agnes Martin (who became a close friend), Jack Youngerman, Barnett Newman, and Robert Indiana. Tawney lived and worked in the New York area until she died in 2007.

Lenore Tawney in her studio on Wooster Street, 1974.

Courtesy Lenore G. Tawney Foundation.

Source: magazine.artland.com/lost-and-found-artist-series-lenore-tawney/

Along with other innovative women artists, Tawney experimented with ideas and techniques that helped to redefine the field of fiber art and expand the potential of weaving as an art form. Through her training as both a sculptor and a weaver, she combined plain weave, gauze weave, slit tapestry, and open-warp weaving to invent large, abstract, and free-hanging sculptural woven forms. They couldn’t be labeled as utilitarian and decorative craft objects; they also didn’t fit in the narrow art categories of that era. Although traditionalists on both sides of the art-craft divide were critical—heretical by orthodox craft standards, yet too “craftsy” by the orthodox art snobs—Tawney didn’t let them daunt her. She stayed true to her own vision and an interdisciplinary creative practice that also included drawing, collage, and assemblage. Superseding the perceived disparity between craft and art, her work gradually emerged on a grand architectural scale. Major institutions have her pieces in their permanent collections.

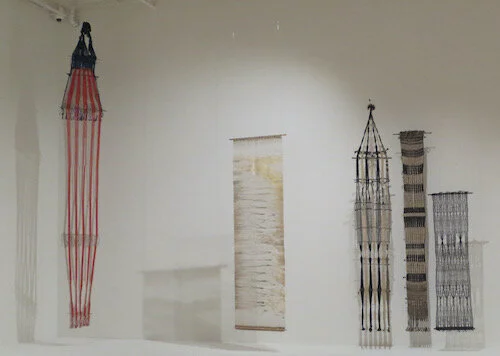

Open-warp weavings by Lenore Tawney. Seaweed (1961) in the center.

Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

Detail of Seaweed (1961), by Lenore Tawney; linen, silk, wool. Lenore G. Tawney Foundation, New York. Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

Untitled Lekythos (1962), by Lenore Tawney; linen, silk, gold, feathers. Lenore G. Tawney Foundation, New York.

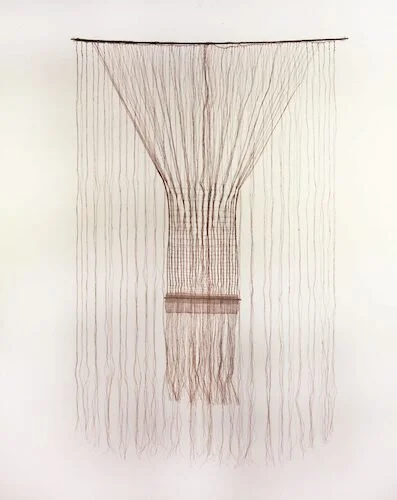

As I walked among the hanging and wall-mounted works, I was struck by the almost ethereal delicacy of the open weaving as well as the light that passes through the spaces between the threads. Such work seems to reflect Tawney’s spiritual pursuit. “All my work should be hung out from the wall, as space or breathing is part of it,” she said in 1982. According to Kathleen Nugent Mangan, director of the Lenore G. Tawney Foundation, the artist had a regular meditation practice. Engaged in Buddhism and yoga, she saw art-making as part of her spiritual pilgrimage. “On numerous occasions,” says Mangan, “she described the creation of her works—the precise lines of her ink drawings, the careful knots and braids that characterized much of her woven work, and the thousands of threads measured, cut, and knotted to form the Clouds—as being a form of meditation.” Tawney said of such work, “I’m not just patiently doing it. It’s done with devotion.”

Cloud Labyrinth (1983), by Lenore Tawney. Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

Being in the room where Cloud Labyrinth was installed felt otherworldly. It’s as though, through all those thousands of unwoven linen threads hanging from a suspended canvas, Tawney was trying to make something invisible visible, but ever so gently and quietly. Any movement of air stirred the threads to dance and vibrate, shifting the light. Coincidentally, she created her series of Clouds as her eyesight was waning. Yet she had to stretch up and direct a thread down thousands of times, perhaps not unlike following one’s breath as it rises and falls—and the space in between—again and again in meditation.

Objects from Lenore Tawney’s studio.

Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

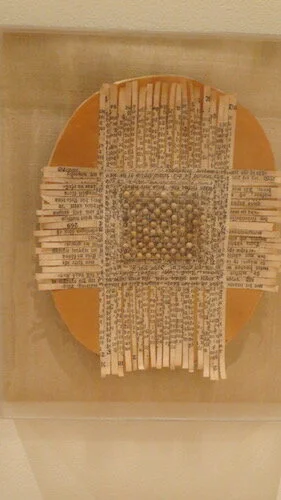

The exhibit’s suite of different rooms afforded a view into Tawney’s diverse practices and interests. One area was an evocation of her studio, with collections of such organic materials as feathers, eggs, shells, stones, and bones, but also bowls, carvings, beads, implements, and much more from her travels around the world. There are drawings as well as assemblages and collages from found objects, indicating that she didn’t allow herself to be creatively confined and that she was fascinated and inspired by what she chanced upon.

Objects from Lenore Tawney’s studio. Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

Assemblage by Lenore Tawney.

Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

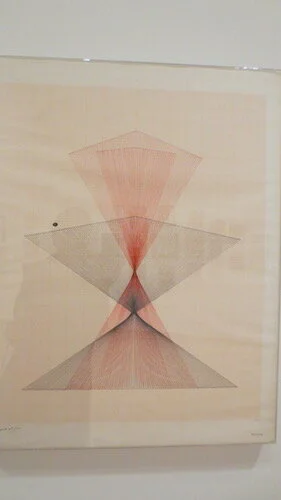

Tawney said about some of her drawings, such as the one below, that they came out of her Jacquard loom experience: “I kept making [them] for the whole year. They were like a meditation, each drawing, each line….I was reading Jakob Boehme, the sixteenth-century mystic, all those years. This title came out of them.” [sorry about reflection in photo]

Gush of Fire (1964), by Lenore Tawney. India ink on paper. Lenore G. Tawney Foundation, New York. Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

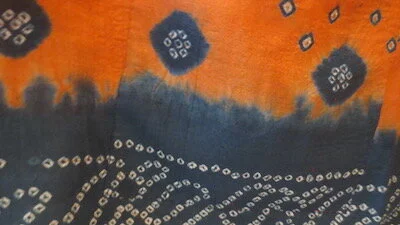

Tawney even created her own clothing.

Resist-dyed dress, silk. Lenore G. Tawney Foundation, New York.

Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

Detail of resist-dyed dress.

Jacquard-woven coat, silk. Lenore G. Tawney Foundation, New York.

Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI.

Detail of Jacquard-woven coat.

I greatly appreciate and respect Tawney’s attitude toward her art-making, one of constantly growing, developing, moving beyond what she had already done. She knew that her work—for example, the open-warp weavings—was controversial because she wasn’t following conventional ways of weaving, but so what. She said, “Well, by the time I was going on to this other work, which simply arrived, I didn’t change my work, it just changed. Then there were people who wanted those open things, and I wasn’t doing them and I couldn’t do them anymore, I was on to something else….” Tawney followed an internal compass, not one imposed by others.

Lenore Tawney. Photo by ? Source:casswebsite.org/blog/2016/1/11/lenore-tawney-working

Living for 100 years allowed Tawney to keep trying different ways to express what was driving her internally, to keep experimenting while pursuing an inner directive, for she considered her studio a kind of sacred environment, one which she used for contemplation and stillness. In an interview, she considers the meaning of her spiritual process for her creative process:

You first have to be in touch with yourself inside very deeply in order to do something, to discover this place is our aim. I want to be under the leaf, to be quiet until I find my true self. I sometimes think of my work as breath.

For Tawney, art and life, creativity and spirituality, were not separate but integrated. As an artist who was captivated by the rhythms and elements of the natural world, especially water, it’s not surprising that the title of the retrospective exhibit is derived from something Tawney jotted down in a sketchbook: “Water is still like a mirror…Mind being in repose becomes the mirror of the universe.”

Because a blog post can’t do justice to Tawney’s full story, the range of her work, and the influence that continues to ripple out on fiber artists, this video offers a brief but closer look at not only the weavings, but also other art forms she created. In addition, for anyone who wants to learn more about Tawney, there are several books to explore, including Lenore Tawney: Mirror of the Universe, by Karen Peterson, editor and former senior curator at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center. And there’s the Lenore G. Tawney Foundation, as well as an oral history interview conducted in 1971.

Questions and Comments:

If you’re already familiar with Lenore Tawney’s work, what strikes you about it?

If you’re not familiar with her work, what’s your response to it?

If you’re a weaver, how has Tawney’s experimentation influenced you?

What intrigues you about her process?